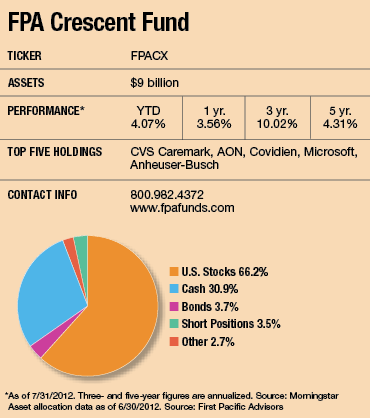

Steve Romick's description of his $9 billion fund as a "free-range chicken" may seem a bit odd, but long-term investors probably aren't bothered by it.

The FPA Crescent Fund, which Romick has managed since 1993, sheds the traditional confines of the mutual fund style cage by scavenging for bargains among a wide variety of investments. He can invest in any size stock based anywhere in the world, shift assets into high yield and distressed debt, short stocks and even nibble at alternative investments such as bank loans.

"Value shows up in different places," he observes. "As long as an investment is liquid, why shouldn't we be able to take advantage of an opportunity?"

The fund's style is also notable for building up substantial amounts of cash if buying opportunities are scarce. At times, in the mid-2000s for instance, Romick has parked north of 40% of assets there.

Better Value In Large Caps

One of the most notable recent changes to the fund has been the size of the companies it focuses on. For most of its life, FPA Crescent mined mostly small-cap and mid-cap names for its stock sleeve, which usually accounts for at least 50% of assets. But over the last three years, it has migrated to larger blue chip names, which Romick believes are more attractively valued and better positioned to take advantage of growth in developing markets.

"Investors have bid up small-cap stocks to the point where they are trading at a premium to large company stocks," he says. "Yet growth prospects for small companies are no better than they are for larger ones."

As a result of the shift, the average weighted market capitalization of the fund's stocks is $31.4 billion, about five times higher than it was five years ago (though still well below the $110 billion weighted average market capitalization for stocks in the Standard & Poor's 500 index).

While the longer-term impact of the move to large caps remains to be seen, the eclectic and changing portfolio has fulfilled its manager's mission to provide equity-like returns with less volatility over the long term than the stock market. According to Morningstar, its performance has landed it in the top 2% over the last 10- and 15-year periods among its moderate target risk peers. But with its large cash allocation, the fund has missed out on some stock and bond market gains so far this year.

Beating the market over a few months or even a couple of years really isn't the point here, says Romick, a 49-year-old Los Angeles native. "We focus on results over a full market cycle of at least seven years," he says. "And we're not benchmark-conscious."

Morningstar analyst Christopher Davis notes that investors might also need to turn a blind eye to the benchmarks from time to time, since Romick's contrarian style and often cash-heavy portfolio means the fund will sometimes lag over short periods. The fund has outperformed over the long term more by preserving capital in down markets than by beating the markets in very bullish periods.

While Davis wonders if the fund's burgeoning asset base eventually could limit Romick's investment flexibility, he notes that the manager "still has plenty of room to employ his opportunistic approach-one he's executed deftly for nearly two decades." Romick says that there have been discussions at FPA about what asset level the fund would have to reach before the managers close it, but he would not disclose a specific number.

Before that happens, investors can still join the ranks of shareholders who have benefited from Romick's deep-value, go-anywhere style, developed in the mid-1980s while he was working for an investment partnership. At the time, an era of Wall Street greed and Predator's Balls, the high-yield bond market was riding high. Romick's appetite for the unloved was whetted a few years later when that market collapsed and many high-yield bonds began trading at extraordinarily deep discounts. "I looked at those distressed bonds and thought, 'Why not,'" he recalls of his decision to venture into a territory others avoided.