Yesterday we discussed the possibility of the Federal Reserve raising rates, and what that might mean for markets. Right now, markets are largely trading on what policymakers are doing—which is to say, interest rates—and as policy normalizes, so, too, should markets. In a normal market, shares will be priced off of earnings, rather than the latest comment from a Fed official.

There’s been a clear disconnect over the past couple of years, as earnings have dropped even as stock prices have risen. This also highlights the problem: if stocks were to be priced on normal policy and normal interest rates, it would imply a significant drop—not something the Fed wants to see.

The Fed has been discussed to death: either it will keep rates the same, in which case the music continues, or it raises rates, which means the game of musical chairs is nearing its conclusion. This won’t bring the story to an immediate end, of course. The Fed may raise rates in bits and drabs over months or years, but the end will be in sight.

What we need to look at now is the fundamental situation, or what it would mean for markets when the Fed eventually acts.

Breaking it down: valuations and earnings

Valuations are typically called out as a big problem (certainly by me), but the underlying issue is earnings. Valuations, after all, are the stock price divided by the earnings. Even more than higher prices, it is poor earnings growth that has brought us to this point. Prices are what they are, but we can dig deeper into earnings to get a sense of what underlies the current high valuations.

Earnings depend on two things: revenue growth and profit margins. Earnings per share (EPS), which is what matters to shareholders and therefore to the stock market, adds another variable—the number of shares. If that drops, even if the other two variables stay flat, the EPS can increase, and that is just what we have seen.

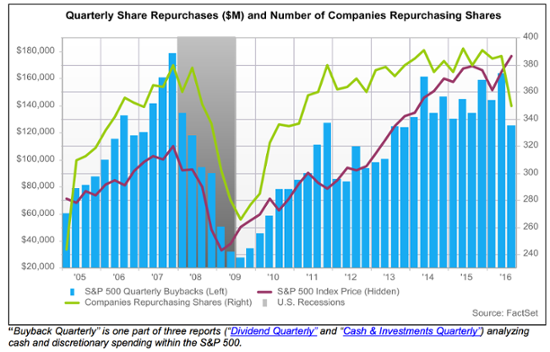

By buying back their shares, companies can reduce the number outstanding and drive their EPS higher, even as revenues remain flat or decline and profit margins do the same. Since the crisis, companies have been buying back ever larger numbers of shares to boost their earnings growth. This past quarter, however, share repurchases dropped, in dollar terms, to the lowest level since 2013, as you can see in the chart below. More important, the number of S&P 500 companies doing buybacks fell to the lowest level since 2010.

Is this a change in trend? Quite possibly, as companies are hitting a financial wall. FactSet’s Buyback Quarterly reports that, for 137 companies in the S&P 500, or almost two-fifths of those doing buybacks, the amount spent buying back shares exceeded what the companies actually earned. Overall, spending on buybacks accounted for more than 70 percent of total S&P 500 earnings, which is not sustainable. Actual buybacks are down nearly 7 percent year-on-year, suggesting that companies are realizing this.

The missing link

Three things have helped earnings growth since the recovery:

• Low interest rates have allowed companies to refinance expensive debt, lowering interest expenses.

• Low wage growth has allowed companies to expand their profit margins.

• Finally, share buybacks have reduced the share count, increasing EPS even as the top line did less well.