When Aziz Hamzaogullari evaluates stocks, he recalls his late Uncle Cahit, who ran a textile export business in his native Turkey. Beginning in middle school, the manager of the Loomis Sayles Growth Fund began accompanying his uncle when he visited his factories and talked to suppliers. The experience drove home the benefits of boot-on-the ground observations, and gave him his first lessons about what makes companies tick. Later, when he came to the U.S. to attend graduate school at George Washington University in Washington, D.C., the virtues of long investment time horizons and “wide moat” investing espoused by value guru Warren Buffett hit home.

Today, the thinking of these role models form the foundation of the investment philosophy behind the fund. Like many growth investors, Hamzaogullari looks for companies that can generate sustainable and growing profits. But he will only invest in their stocks when they sell at a significant discount to estimated intrinsic value. The methodology means examining how stock investors view a company’s value and comparing that with what a private buyer might pay.

“We invest in businesses, rather than the market,” says Hamzaogullari. “All else equal, the larger the discount between market price and our estimated intrinsic value, the greater we view our margin of safety.” By his estimate, the 33 stocks in his portfolio were selling at a 35% discount to their intrinsic value at the end of 2015, the latest publicly available figure. Since he took over managing the fund in June 2010, the discount has ranged from 25% to 50%.

Another key differentiator is an ultra-low 10% portfolio turnover rate at the fund since Hamzaogullari began managing it in June 2010. As an investor with a long time horizon, his goal is to buy a company when other investors are overreacting to temporary bad news—either the company’s or the general economy’s—when it has little to do with the company’s long-term intrinsic value. The high conviction portfolio added just one new name in 2015, three in 2014 and one in 2013.

To gain entry into this small club, companies must generate sustainable and profitable growth, have strong cash flow and sell at a significant discount to intrinsic value. They must also have business models that are difficult to replicate and management that takes a long-term view instead of focusing on short-term incentive goals. Both before and after he buys their stock, Hamzaogullari visits companies and speaks with managers regularly to make sure they are working in the long-term interests of the business. And like Uncle Cahit, he also talks to suppliers and customers to gain a knowledgeable outsider perspective.

He points out that while the average CEO has tenure of only about four years, most CEOs in his portfolio companies have been around much longer than that. “About 40% of our companies are run by their founders,” he says. “The rest are run by people with a long-term focus.”

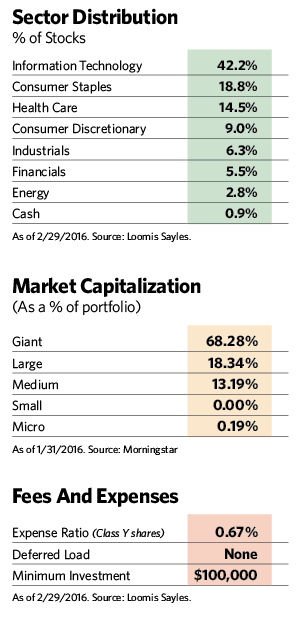

The portfolio differs markedly from its benchmark Russell 1000 Growth Index in a number of respects, and its “active share” (a measure of how it differs from the benchmark) has been at or above 80% since he took over. Among other things, the portfolio has slightly higher trailing and forward price-to-earnings ratios than the index, and higher projected earnings per share growth. It also has a much larger presence in information technology and consumer staples companies, and a smaller one in industrials.

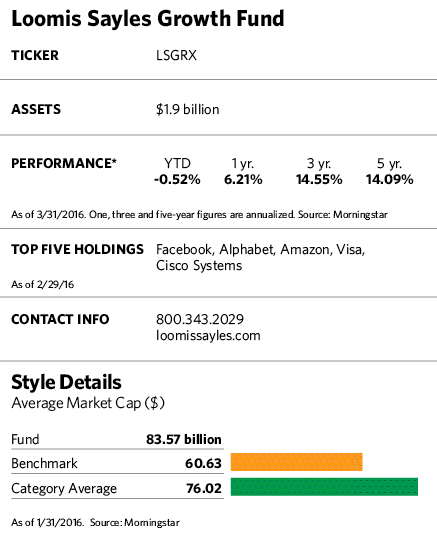

While high active share does not ensure outperformance, Hamzaogullari believes it’s “a necessary condition for generating alpha and outperforming a benchmark net of fees.” The fund’s Class Y shares have a net expense ratio of 0.69%, and the fund’s performance has more than made up for that expense. Over the last five calendar years, it has had an average annualized return of 14.66%, while the benchmark’s was 13.53%. Over the same period, it has beaten out 99% of the funds in Morningstar’s large-cap growth category.

The manager’s highly active style contrasts sharply with the popular practice of indexing, or so-called active management that hews closely to an index. “Defining risk in relative terms obfuscates the fact that the benchmark itself is a risky asset,” he says. “This is particularly true with cap-weighted indices because downside risk increases significantly when the stocks of a particular sector experience a run-up in prices that are above their fundamental intrinsic value. If a portfolio manager ties his investment decisions to benchmark holdings and risk factors, he must necessarily take on this additional downside risk.”

The stocks in his own eclectic portfolio run the gamut from old-school brand names such as Coca-Cola (whose managers happened to be paying his office a visit just before our interview) to newer tech blue chips such as Amazon and Facebook.

Hamzaogullari says the latter company holds a competitive advantage because of its strong brand, network, scale and a “social advantage” of having users with real identities. The company has over 1.5 billion users globally, and 85% of them are from outside the U.S. Its margins and cash-flow generation are very strong, and founder Mark Zuckerberg maintains a long-term focus and strong strategic vision. Going forward, the company is poised to take advantage of the ongoing global shift from traditional to online advertising.

“We believe the assumptions embedded in Facebook’s current stock price show a lack of appreciation for the company’s significant long-term growth opportunities,” he says. “Facebook shares are trading at a significant discount to our estimate of its intrinsic value and offer a compelling risk-to-reward opportunity.”

Amazon, meanwhile, benefits from a well-known brand name, from being large, from having a sophisticated technology platform, and from having a broad logistics and distribution system. That gives the company, a top holding in the Loomis fund, a competitive edge that would be difficult to replicate.

Amazon has a leg up on traditional brick-and-mortar retailers because it doesn’t require physical inventory in numerous locations. Instead, it keeps inventory in fewer fulfillment and distribution centers, which allows for higher inventory turnover, lower capital requirements, high returns on invested capital and strong free-cash-flow generation. Founder Jeff Bezos, still at the helm of the company, owns about 17% of the business and is its largest shareholder.

A Believer In Megacap Growth Stocks

May 2, 2016

« Previous Article

| Next Article »

Login in order to post a comment