These days, it seems like everyone in the bond market is obsessed over what will happen when the Federal Reserve starts whittling down its mammoth, crisis-era investments in U.S. government bonds.

Yet lost in the hullabaloo is one little-noticed fact: there’s an even bigger debt pile that could draw buyers away from Treasuries at just the wrong time.

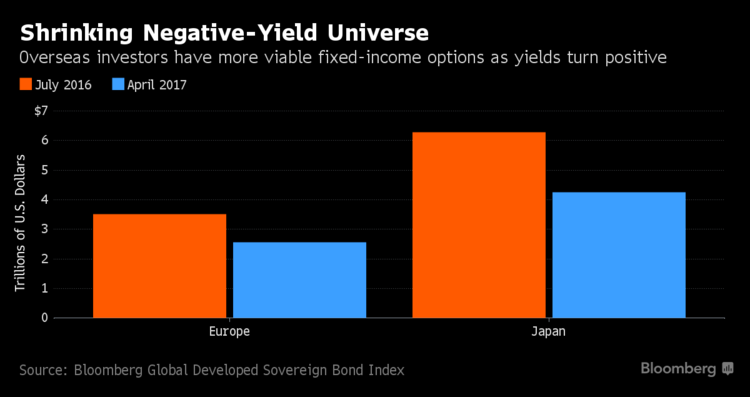

In overseas markets, more than $3 trillion of negative-yielding government bonds -- which all but guarantee losses for buy-and-hold investors -- have turned positive in recent months. And analysts say that number may grow over the next few years as brighter economic prospects and shifts in monetary policy lift trillions more out of sub-zero levels in Europe and Japan.

The consequences for the U.S. bond market could be significant. Simply put, foreigners who have poured vast amounts of money into higher-yielding Treasuries may be less inclined to do so now that they have more viable fixed-income options at home. Any sustained retreat could lead to painful losses, particularly at a time when Fed officials are suggesting the central bank may finally be ready to pare its holdings, which include $2.46 trillion of Treasuries.

“There may no longer be a tsunami of money coming from Europe and Japan,” said Torsten Slok, the chief international economist at Deutsche Bank.

Foreigners currently own 43 percent of the $13.9 trillion Treasury market. With the Trump administration’s pro-growth agenda likely to swell the public debt burden in coming years, they’ll be crucial in helping hold down long-term borrowing costs as the Fed raises interest rates.

Of course, nobody is suggesting an outright exodus. Bond yields in places like Germany and Japan are still minuscule compared with those on 10-year Treasuries, which stood at 2.38 percent as of 6:21 a.m. New York time.

Excluding the U.S., yields in developed nations average just 0.51 percent. About $6.8 trillion (or almost 30 percent) of the securities in the developed world are still stuck in negative territory, a legacy of quantitative easing as well as a reflection of how Europe and Japan still face stronger economic headwinds.

But there’s no denying yields have drifted higher since July, when the Brexit vote pushed investors into haven assets.

German 10-year bunds now yield 0.23 percent after plumbing a low of minus 0.205 percent in July. French yields have jumped almost 10-fold to 0.89 percent, while those on Japanese bonds have been pinned in positive territory since mid-November. In all, more than $2 trillion worth of Japanese bonds and about $1 trillion of debt in Europe have turned positive.

Specific reasons vary from country to country, but analysts agree the shift in investor expectations has a lot to do with the growing sense that central banks realize the grand experiments with QE may have run their course. Last September, the Bank of Japan gave up its “ shock-and-awe” approach to stimulus in favor of targeting yield levels. Societe Generale says the European Central Bank will start scaling back its bond buying in October.

“The ECB and Bank of Japan debt purchases, even as the Fed stopped their quantitative easing, had been supporting bond markets” in the U.S., said Subadra Rajappa, the head of U.S. interest-rate strategy at SocGen.

Now, the simple fact that yields have flipped has persuaded some non-U.S. investors to bring more of their money home.

Asset managers in Japan yanked 1.07 trillion yen ($9.7 billion) from overseas debt securities in February, after sending a record 5.45 trillion yen abroad in July. The shift is far less pronounced in Europe, yet net fund outflows have also eased since surging to $717 billion in the 12 months ended September, data compiled by Deutsche Bank’s Slok show.

“Having more positive yields at the margin widens the opportunity set in Europe,” said Frances Hudson, Edinburgh-based global thematic strategist at Standard Life Investments, which oversees $360 billion. She said the firm trimmed its Treasuries allocation in the past six months because the U.S. is further along in the economic cycle as well as the rate cycle.

By one measure, coming to the U.S. might not be worth the hassle. After accounting for the cost to hedge against the dollar’s ups and downs -- a common practice for those that invest abroad -- 10-year Treasuries yield just 0.4 percentage point more than German bunds.

The turnabout is even starker for French bonds. They yield almost 0.3 percentage point more than currency-adjusted Treasuries. As recently as two years ago, hedged U.S. notes offered a 1.2 percentage point pickup.

For now, the unraveling of the reflation trade has helped to keep Treasury yields in check. But as the Fed lays the groundwork for unwinding its debt holdings, any pullback by foreigners could spell trouble.

“There is an under-appreciation in U.S. financial markets of the very, very significant role that rest of the world has played,” said Slok. If overseas investors retreat, “the U.S. will be hit.”

This article was provided by Bloomberg News.