David Knall, an investment advisor and managing director in Stifel Nicholas' Indianapolis office, says the defensive aspects of RMBS provide a margin of safety. "We right now are interested in preservation of capital and making a respectable return," he says. A study by Barclays Capital earlier this year bears out this claim, predicting high-yield corporate bond returns of 5.5% to 6% after accounting for future defaults, versus 7% to 12% loss-adjusted returns in non-agency RMBS.

A Persistent Opportunity

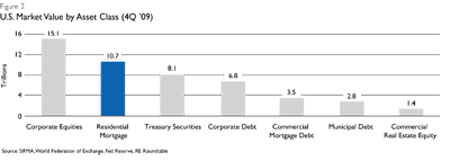

The housing crisis has redefined an enormous asset class. That U.S. residential mortgages have previously escaped notice is surprising, considering that they constitute the nation's second largest investable asset class, valued at $10.8 trillion (Figure 2). To date, limited competition has enhanced returns, partly because many residential mortgage hedge funds were impaired-or disappeared-in 2008. (The same can be said for a number of Wall Street dealers and bank proprietary trading desks .) "It's a large sector, and the hedge funds make up a very small component of it," says Deepak Narula, principal of Metacapital Management.

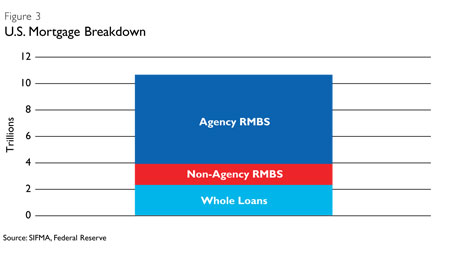

The asset class is also diverse, offering investors a range of sectors and trading opportunities (see sidebar, Figure 3). Although strategies differ considerably in structure and form, all seek to exploit diverse views regarding prepayment speeds, interest rates, fundamental value and technical dislocations.

Managers continue to see opportunity in the agency RMBS market, for example, because many borrowers lack equity in their homes-resulting in unusually low levels of refinancing and, consequently, slower mortgage repayments. "Declining home prices have held prepayments in check," Narula says. "When it comes to qualifying for refinancing, appraisals show your loan-to-value is too high."

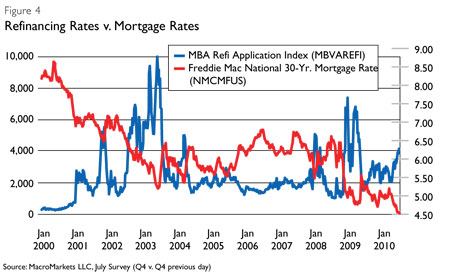

Even for those who have positive home equity, stricter underwriting standards and higher upfront fees have significantly reduced the incentive to refinance. As a result, Wall Street mortgage prepayment models that previously assumed that low mortgage rates lead to high refinancing rates are no longer reliable (Figure 4). "Models do not account for what may happen with declining home prices. Of course, anticipating tighter underwriting is even harder. Clearly, the models got it wrong," says Metacapital's Narula.

Over the last two years, investment managers who correctly predicted that refinancing rates would be lower than the Wall Street models predicted have garnered very high returns. Their strategy? Buying cheap interest-only mortgage bonds from sellers who feared a refinancing wave would cut short the flow of interest payments prematurely. To date, that refinancing wave has not materialized, and the bond buyers have collected handsome cash flows.

Non-agency RMBS is also attractive, albeit for reasons more relative to supply and demand than divergent views on prepayment speeds. Non-agency RMBS has appreciated throughout 2010 thanks to steady demand in combination with amortization and a lack of new issuance. From an outstanding balance of about $1.6 trillion at the beginning of the year, analysts project that the market will contract by $300 billion in 2010, according to a recent report by Goldman Sachs. Supply of new non-agency RMBS is virtually non-existent because of tougher mortgage origination standards and more stringent guidelines for rating agencies. "The rating agencies are very conservative and very concerned about making the same mistake twice," Rosenthal says. "Their credit enhancement levels have increased dramatically. Making new loans and selling them in the securitization market is not a positive economic event, so why would you make new loans? Ultimately, the origination is just ending up on bank portfolios and not being securitized."