Some concepts take on a life of their own and grow far bigger than the original idea. William Bengen's paper, "Determining Withdrawal Rates Using Historical Data," from the October 1994 Journal of Financial Planning answered one question, spawned a slew of further research and has even become a rule of thumb--the "4% rule." Subsequent work by Bengen himself coined the term SAFEMAX and produced a terrific book, Conserving Client Portfolios During Retirement (FPA Press). I lost track a long time ago of all the papers written about safe withdrawal rates, portfolio sustainability and similar issues.

Last month, I had the pleasure of receiving a not yet published paper from Wade Pfau, an associate professor at the National Graduate Institute for Policy Studies (GRIPS) in Tokyo. Pfau earned his Ph.D. in economics at Princeton in 2003 and has contributed to the body of knowledge most recently through a Journal of Financial Planning contribution examining how well (or poorly) the 4% rule held up in other countries.

His latest work examines the retirement issue in a different way. Pfau noticed that the preponderance of research has sought a safe withdrawal rate, which is then used to compute a target for how much wealth needs to be accumulated so that desired retirement spending can be funded from this wealth at the desired withdrawal rate. Research on preretirement is mostly about how to achieve a wealth accumulation target. Most consumer-oriented discussions about retirement similarly examine accumulation separately from decumulation.

Pfau wondered what would happen if he linked the accumulation and decumulation phases together in an integrated whole. "My findings suggest that a fundamental rethink about retirement planning is needed. When linking the accumulation and decumulation phases together, the concepts of 'safe withdrawal rates' and 'wealth accumulation targets' end up serving as almost an afterthought. Focusing on them is the wrong way to think about retirement planning."

Pfau's paper "Safe Savings Rates: A New Approach to Retirement Planning over the Lifecycle" wanted to bring some framing to the question of how much one needs to save that recognized both one's saving for retirement and one's spending through retirement. If there is a "safe withdrawal rate" there should be a "safe savings rate." At what rate of savings does it always work out?

To get to this rate, he set up the problem like this: "The baseline individual wishes to withdraw an inflation-adjusted 50% of her final salary from her investment portfolio at the beginning of each year for a 30-year retirement period. Prior to retiring, she earns a constant real salary over 30 working years, and her objective is to determine the minimum necessary savings rate to be able to finance her desired retirement expenditures. Her asset allocation during the entire 60-year period is 60/40 for stocks and bills. Data is from Robert Shiller's Web page for the S&P 500 and Treasury bills."

Put another way, consider a person making $100,000 today who expects that salary to increase with inflation and who wants to withdraw $50,000 in today's dollars from their portfolio to supplement any other income, adjusting for inflation over a 30-year retirement. Based on market behavior since 1871, a 60/40 mix, and ignoring taxes, there was never a time where saving at least X% of their salary for 30 years prior to that retirement didn't achieve those goals. Pfau solved for X.

The term "replacement rate" is used throughout the paper but this is not to be confused with how that term has been used often in the past, that is "one needs 80% of pre-retirement income to be comfortable in retirement." As financial planners know, that rule-of-thumb replacement ratio approach is often meaningless because some people will need more than a particular rate while others less. It can be tricky to incorporate that idea properly into research. Pfau is focusing only on the amount needed to come from the portfolio, not an overall replacement rate.

With Schiller's data going back to 1871, Pfau could examine 30 years of savings followed by 30 years of withdrawals. Retirements would therefore have beginning dates ranging from 1901-1980. He also could extend the time frames of Bengen's SAFEMAX examination.

This second look at SAFEMAX highlighted to Pfau the extreme volatility of the withdrawal rates. Maximum withdrawal rates ranged from just over 4% to 10% in some periods. As one might expect, the higher withdrawal rates correlated to better markets and the lower rates to weaker markets during retirement.

The corresponding effect on the amount of assets required at the beginning of retirement to sustain a desired withdrawal rate mimicked this result. If markets did well during retirement, less was needed to start the final 30 years and if markets were poor, more was needed.

Of course, a retiree does not know what the markets will do ahead of time. So assuming that the goal was to accumulate enough to use a 4% withdrawal rate, Pfau calculated what savings rate was needed to accumulate that amount. This is very similar to how most people approach retirement planning--isolating an accumulation goal to support an isolated set of parameters during decumulation.

The savings rates required to accumulate enough to employ the 4% rule were every bit as volatile as the differing withdrawal rates. They ranged from 10.89% to 37.7%. When Pfau noticed that the periods of high required savings corresponded to periods where far less was actually needed during the subsequent retirement, he abandoned the 4% number and used actual retirement results to determine the needed savings. The volatility of the needed savings amount dropped significantly.

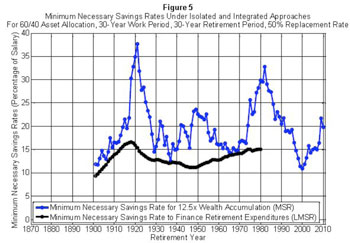

Figure 5 illustrates the difference between saving to make a targeted amount with a 4% withdrawal rate (blue line) and the savings needed based on actual results. Pfau frames the blue line as an accumulation of 12.5 times salary, which is the needed amount to have 50% of salary equal 4%. He calls the black line the lifecycle-based minimum savings rate (LMSR) needed to finance the desired expenditures and considers the black line the main contribution of his paper.

So what is X under the baseline case that I described earlier? Saving 16.62% of salary would have worked every time. Pfau also provides a matrix that shows results when certain variables change. It lays out 20-, 30- and 40-year savings spans; 20-, 30- and 40-year retirement periods; 40/60, 60/40 and 80/20 allocations; and replacement rates of 50% and 70%. For the typical 30-year retirement time frame, saving for 40 years cuts the safe savings rate to 8.77%, while saving for only 20 years increases the safe rate to over 30%.

One reason for the much higher consistency of the needed savings is that good market environments tend to follow bad ones and visa versa.

I can't help but think of some of the work Michael Kitces, author of The Kitces Report newsletter and the blog Nerd's Eye View at Kitces.com, has done relative to valuations and sustainable withdrawal rates. Low valuations portend better returns and therefore higher sustainable withdrawals. High valuations suggest lower withdrawal rates. Pfau isn't looking at valuations and Kitces is quick to point out that valuations aren't particularly great timing tools, but both shine some light on the effect of the good returns that tend to follow bad returns that tend to follow the good, and so on.

One of Kitces' blog posts pointed out just how much most people depend on the last few years of savings to meet an accumulation goal and some of the implications of relying on the returns leading up to retiring. It was such a good question and post, the NY Times picked up on it for a January 22 column. Pfau's paper suggests that tough years just prior to retirement may not be as problematic as one might fear.

While the "16.62% Rule" doesn't exactly roll off the tongue, I look forward to the additional research I hope this lifespan approach generates. The science of financial planning has always fascinated me.

I'm also quite taken by the "art" elements of the profession. I've read through the paper several times, and each time I come up with a few more interesting twists and turns from a behavioral standpoint. I have so many ideas running through my mind I could write a book on the subject. At the very least I have plenty of material for more columns.

You should be able to see the paper for yourself soon.

Dan Moisand, CFP has been featured as one of the America's top independent financial advisors by most leading financial advisor publications. He has spoken to advisor groups on five continents on topics such as managing investments and navigating tax complexities for retirees, retirement readiness, and most topics relating to the development of the financial planning profession. He practices in Melbourne, FL. You can reach him at 253-5400 or [email protected]