Not long ago, emerging market debt was viewed as the most speculative corner of the bond market. The Asian currency crisis in 1997 and Russia's massive debt default the following year crushed bonds issued by emerging markets in Asia, Europe and Latin America. In 1998, emerging markets bond funds fell nearly 23%, on average. During the 2008 credit crisis, they fell about 18%.

More recently, however, the bad boys of the bond world have morphed into up-and-coming role models as investors gravitate to the attractive yields and improving risk profiles of emerging market bonds.

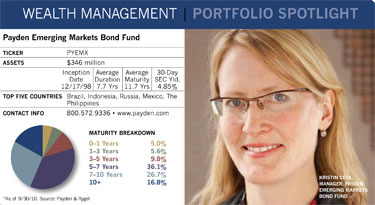

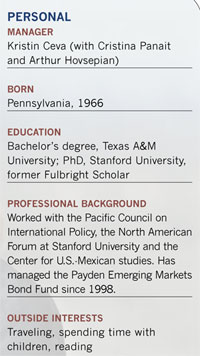

"Today, many emerging markets have more sustainable debt dynamics than developed markets," says Kristin Ceva, the manager of Payden & Rygel's Payden Emerging Markets Bond Fund. "The divergence in macroeconomic development between emerging markets and developed markets is unprecedented."

As established markets struggle with huge debt levels and slow economic growth, many emerging market countries are meanwhile less leveraged and enjoy solid economic growth. In emerging markets, the average debt to GDP ratio-a measure of government debt as a percentage of gross domestic product-stands at around 40%. For developed countries with slower growth and more leverage, that figure is about 100%.

Emerging market bonds also have higher yields than most other types of fixed-income securities, which is a major reason investors have been flocking to the group since last year. By the end of August 2010, retail and institutional inflows into emerging market bond investments for the year had totaled nearly $50 billion, and they are expected to reach $70 billion by the end of the year, according to J.P. Morgan Chase. That's more than double the inflows of $33 billion for all of 2009.

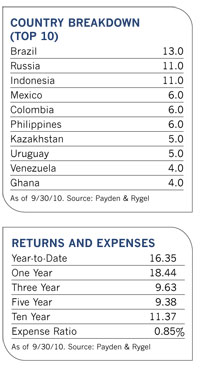

Investors see bonds as a tamer way than equities to tap emerging market growth, Ceva says, adding that a growing number of investors who like the emerging markets story are complementing equity allocations with debt. Since 2000, calendar year returns for the fund have ranged from a low of -10.28 in 2008 to a high of 28.9% in 2009. By contrast, returns for the moodier iShares MSCI Emerging Markets Index ETF (EEM), which follows emerging market equities, have bounced from -49% in 2008 to 68% in 2009.

"Over the last 15 years, emerging market debt has had better performance and lower volatility than emerging market equities," she says. "Financial advisors and pension funds tell me they have a long-term strategic allocation to emerging market debt of 10% to 20% of a fixed-income portfolio."

The influx of money has pushed up bond prices and driven down yields. In recent years, the yield spread between emerging market debt and comparable U.S. Treasurys has ranged from about 200 basis points in 2007 to 800 basis points during the credit crisis in 2008. This year, the yield advantage for emerging market bonds has settled into the 290-to-330 basis point range.

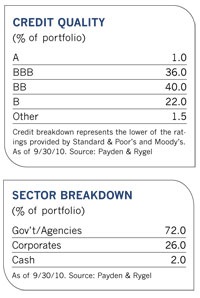

She believes the yields on these bonds remain more attractive than they are on many other types of bonds. "Those spreads are about the same as they were in 2005," says Ceva. "But you have to remember that the credit quality of emerging market bonds has improved about two notches since then. It's a totally different asset class than it once was."

The improved credit quality comes after years of effort by some emerging market countries to shore up their balance sheets and reduce dependence on foreign creditors. As developed nations ramped up borrowing to prop up failing economies in 2008, these growing countries were able to keep their debt in check thanks to strong exports, buoyant commodity prices and economic growth.

Today, over half of the sovereign universe is rated at investment grade, where only 5% was in 1993. The average quality of the JP Morgan EMBI Global Diversified Index is Baa/BB+, which falls just shy of investment grade. And while the fortunes of companies tend to be cyclical, "the structural transformations in many emerging market political and economic systems are unlikely to reverse in the near term," says Ceva. She expects defaults on sovereign bonds to be less than 1% in 2010, and expects credit upgrades to exceed downgrades.

In Ceva's view, the biggest threat to total return over the next year would be rising interest rates, since emerging market bonds typically have longer maturities than many other types of securities. Rising rates could also heighten investor aversion to risk, which could reignite emerging market phobia and drive investors away from both stocks and bonds in those markets.

But she doesn't think that's likely to happen. "In a low-interest-rate environment, which appears likely for some time to come, investors will be drawn to a fixed-income alternative that offers high credit quality and attractive yield," she says.

Quality Varies

Since the economic health of these countries and their credit quality are uneven, with bond ratings that run the gamut from admirable to abysmal, country selection is critical in this space. The bonds issued by nations such as China, Chile and Poland sport ratings of 'A' or higher, for instance. But other bonds, such as those issued by Greece, Ecuador and Iceland, have ratings below investment grade and are backed by countries mired in debt. With ratings in the 'BBB' area, the lowest Standard & Poor's investment grade, many emerging market country bonds are relative newcomers to the world of higher-quality debt.

To help control risk, the Payden fund invests in securities from at least 15 countries, with each country accounting for no more than 20% of assets. The fund's latest fact sheet shows 69% of assets in government bonds, with 26% in corporates and the rest in cash equivalents. There are no structured products or credit derivatives among the fund's holdings.

In deciding country allocations, the first step in the investment process, Ceva looks for nations with consistent and appropriate economic policy, with strong financial and banking systems, with the potential for economic growth and with reasonable debt burdens. She also analyzes a country's political and social institutions and its government's ability to enact structural reforms. To get firsthand knowledge, she often travels to speak with different countries' government and banking officials.

The countries with the highest ratings don't always get the nod. China, the one perhaps most identified with emerging markets, has a solid 'A+' rating with S&P. Yet Ceva's fund has no investments there because the strong foreign demand for the bonds has compressed yields to the point where they are no longer attractive.

Brazil, however, she considers an area of opportunity, and the country represents 13% of the portfolio. Although its bonds are at the lower end of the investment-grade spectrum, Brazil will likely experience economic growth of about 7% this year. Ceva was impressed by the country's economic resilience during the 2008 credit crisis, and notes that its debt has been decreasing in relation to GDP over the last several years.

Indonesia, which she calls "the second 'I' in BRIC," represents the fund's second largest country weighting at 11% of assets. The country has a population of 250 million people and strong growth in domestic demand for products. The total sovereign debt is a modest 34% of GDP, and its government has demonstrated prudent economic policy management. Ceva believes the government bonds could move into investment-grade territory over the next year. Such a credit upgrade would open up a new range of investors such as pension funds.

Bonds issued in Russia also look attractive, and are less expensive than other investment-grade sovereigns, in part because of the fallout from the European debt crisis. However, the country has an extraordinarily low level of debt given its economic growth rate, and stands to benefit from higher oil prices.

After pinning down country allocations, Ceva looks for the best ways to pick up yield in each country. About 20% of the fund is invested in local currency government and corporate bonds, which offer higher yields than dollar-denominated bonds from the same countries.

Although government bonds make up the bulk of fund assets, the portfolio also has a significant allocation to the bonds of private companies and quasi-private companies with some government ownership. Since demand for government bonds has led to higher prices and lower yields, emerging market corporates have offered investors a different pathway to higher yields.

Ceva avoids distressed debt. She focuses instead on better quality companies that operate in countries she likes and that boast ample free cash flow, low debt, experienced management and sufficient access to capital markets. Her preferred companies must also offer an attractive yield pickup over government bonds to justify the added risk of investing in them.

One holding that fits her criteria, Brazilian metals and mining company Vale S.A., yields about 200 basis points more than comparable U.S. Treasury securities and about 50 basis points more than Brazilian sovereign debt. Another Brazilian corporate holding, JBS, is the largest beef and chicken producer in the world. Its bonds yield about 8%. Another debt holding, the diversified India mining company Vedanta Resources, also yields about 8%.