After many years of low inflation, many investors and their advisors have become complacent about incorporating inflation considerations into their investment strategies. But they should take note: Inflation is an insidious risk that erodes long-term purchasing power and the value of many asset categories.

Advisors need to quantify inflation's impact on their clients' future needs and their portfolio strategy. The conundrum is how to assess this risk and position portfolios without sacrificing returns.

China, India and many other emerging economies are already battling inflation by raising interest rates and bank reserve requirements. Commodities are marking new highs while emerging market consumers are helping fuel increases in energy and food prices.

Most wealth advisors help clients calculate potential portfolio returns and risk of loss in value. But clients also need help in accurately quantifying the impact of inflation on their long-term needs and addressing these needs with specific asset allocations. The key is determining exactly what is needed to incorporate a long-term inflation benefit into a conservative portfolio. In this case, "conservative" includes the goal of preserving purchasing power.

Portfolio Adjustments

Consider the hypothetical case of Joe, a 60-year-old businessman who has sold his firm for $22 million, giving him a $25 million portfolio. This includes accumulated savings, sales proceeds from the business and his IRA, but not his personal real estate. Joe wants to spend $700,000 per year for the rest of his life, which he hopes will span 40 years, and pass on some assets to his wife and children. He expects his tax bracket to be in the 40% area.

At first glance, $700,000 is only about 2.8% of his total portfolio, after taxes in current dollars. This has Joe feeling that he can easily achieve his goals-but his is a false comfort. A deeper look at the numbers reveals unacceptable inflation risk.

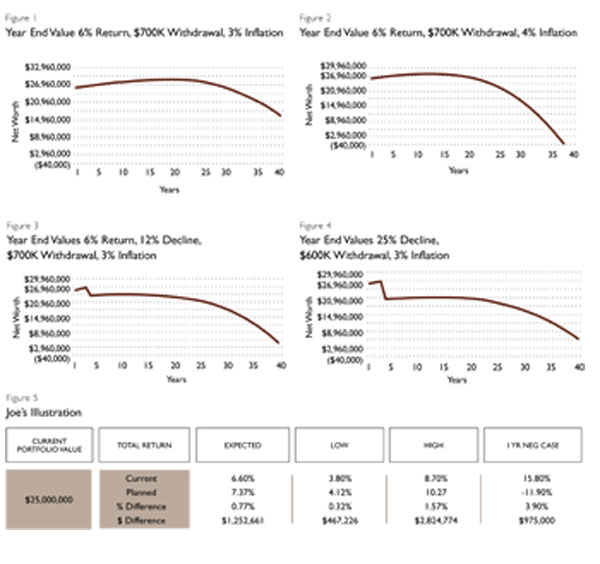

Figure 1 shows the year-end value of Joe's portfolio, assuming he earns a 6% pretax return and withdraws $700,000 a year adjusted for inflation. After 40 years, Joe has $16.4 million of nominal dollars, and the $700,000 in current dollars withdrawn annually will have grown to $2.2 million a year, an increase of 217%. The required rate of return for the portfolio annuitized to zero over 40 years is 4.92% pretax and 2.95% after tax.

For context, 40 years ago, a New York City subway fare was 30 cents. Today, it's $2.25. A slice of pizza was 35 cents, and now it's $2.75. Inflation as measured by the U.S. Consumer Price Index averaged 4.4% during this period. Figure 2 is the same year-end graph but with 4% inflation.

For the first 20 years, Joe's nominal dollars are still above $25 million, but his expenses are growing faster than his portfolio's value and its ability to generate higher future nominal dollars.

Joe reaches a tipping point when he starts to withdraw capital to meet expenses. He is diminishing his portfolio's value below the point at which it can meet inflation-adjusted expenses. At age 80, Joe either has to cut back on his lifestyle, get a job or take more investment risk to hopefully earn a higher return.

Making these necessary adjustments at age 80 is a lot more difficult than it would have been if an advisor had proactively quantified inflation's impact decades earlier. Joe's situation was mathematically obvious and could have been avoided.

With inflation at 4%, Joe needed to earn a pretax return of 6.5%. A 1% increase in inflation from 3% to 4% caused his required return to increase by 1.68%. In this case, some of his portfolio should be allocated to investments that are likely to perform especially well in a more inflationary environment.

How Much Risk?

What happens when the capital markets suffer an interim decline in an inflationary environment?

Again, a quantified portfolio approach solves this equation. At 3% inflation, Joe needed a 4.92% return to have his assets last 40 years. If his portfolio declines by 12% in year three, for example, his required rate of return for the remaining 36 years increases to 5.97% (See Figure 3).

Perhaps Joe is very fearful of another cataclysmic financial crisis. By simply deciding to spend more conservatively-$600,000 per year instead of $700,000-he can dramatically lower his risk. As can be seen in Figure 4, Joe can now absorb a 25% portfolio decline in year three.

Now that we've determined Joe's required rate of return, its sensitivity to inflation, capital withdrawals and the impact of portfolio declines, we can start building an asset allocation. The key variables for advisors to consider with their clients are as follows:

Liquidity and stability: Investors should have sufficient liquidity to be able to withstand a multi-year bear market and not be forced to sell volatile assets in adverse market environments. Five years of liquidity is a good starting point, but seven to ten is better.

In Joe's case, spending $600,000 a year requires $3 million to $6 million in high quality, very liquid short-term fixed income investments. In addition to a reserve to fund needed withdrawals, these liquid and stable assets are a source of funds to take advantage of the low prices or high yields usually associated with volatile and troubled, dislocated markets. They enable investors to react with boldness when bargains are available in down periods when fear predominates.

Liquidity premiums: Less liquid assets such as municipal tax liens, real estate and high-yield and distressed asset-backed securities provide a substantial potential premium compared to more liquid assets with similar risk. With substantial liquidity as a portfolio anchor, investors can make some commitments to less liquid investments and potentially earn these excess returns.

Currency risk: Investors face the risk that their base currency is devalued relative to others, impacting future expenses. A decline in the dollar may make energy more expensive for U.S. dollar buyers but not necessarily Chinese and Indian buyers if their currencies are appreciating relative to the U.S. dollar. Investors need investments outside of their base currencies, as well as investments in consumable commodities, to offset base currency declines.

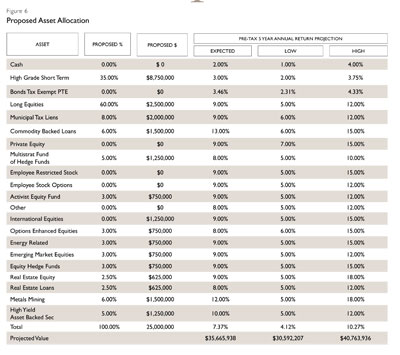

Therefore, rather than the "traditional" 60-40 stock-to-bond approach, our quantified portfolio for Joe looks as follows:

35% in very high quality, very liquid and very short-term bonds that can fund more than ten years of his anticipated cash needs, offsetting his less liquid assets;

28% in less liquid, higher potential return strategies, since Joe doesn't need all of his assets liquid at once;

17% in non-U.S.-dollar-based investments and/or global commodity markets, hedging against dollar depreciation.

This asset allocation adds 77 basis points of return per year over a five-year period. Based on Joe's initial $25 million portfolio, this amounts to an additional $1.25 million. This is in addition to higher potential returns in the low and high cases, and substantially less risk in the one-year negative case. The negative case also assumes that each asset class has its negative case at the same time. This is most unlikely, but useful for planning purposes (See Figure 5).

Figure 6 shows our approach.

A Roadmap

This asset allocation plan is a roadmap to success. While it's based on our five-year capital market projections, clients can substitute their own if they are more bullish or bearish regarding specific asset classes. This can form the basis for an important discussion with clients.

While we can't anticipate every event that might positively or negatively affect the global economies and markets, it is important to position portfolios to benefit from inevitable market disruptions that depress prices or increase yield when markets are under economic or liquidity pressures. These situations often provide extraordinary investment opportunities for investors whose portfolios have held up well and have sufficient liquidity to invest during times of stress.

The bottom line is that by looking at a portfolio as if it were a business-quantifying future cash flows and their sensitivity to inflation-advisors are more apt to truly help investors determine if they have enough money to accomplish their long-term goals. This is especially critical given the potential inflationary environment on the horizon, and the recent bear market that has already done much to erode client portfolios and investor confidence.

Hugh R. Lamle is president of M.D. Sass, an investment management firm serving institutional and high-net-worth investors. He can be reached at [email protected].