International factors can help explain the relative resilience of longer-term bonds from mid-February to the start of March. Since Treasury yields bottomed on February 11, 2016, the 2-year Treasury yield has increased by 0.15% compared with a more muted 0.09% rise in the 10-year Treasury yield. The relative resilience of longer-term Treasury bonds continued again last week (February 22–26, 2016), as short-term yields rose more than intermediate- and long-term yields.[1]

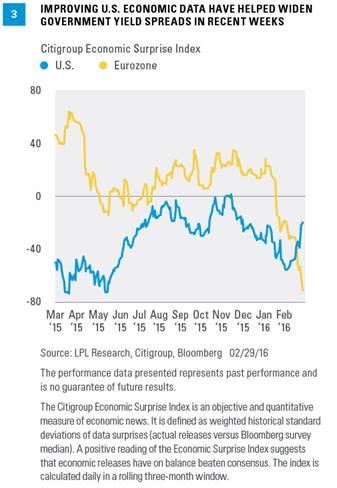

U.S. Treasuries yield notably more compared to government bond yields of other major developed countries. Beauty is often in the eye of the beholder, or in this case, the bondholder [Figure 1]. The allure of U.S. Treasury bonds to international bond investors remains strong and helps explain why intermediate- and long-term interest rates have proven more resilient.

To be sure, lingering uncertainty over China, fallout from weakness in the energy and mining industries, as well as sluggish global growth have also played a role in Treasuries holding on to strong gains to start 2016.

Still, the yield advantage of U.S. Treasuries has actually increased in recent weeks as overseas bond yields have continued to fall. The yield advantage of the 10-year Treasury relative to the 10-year German bund increased by 0.2% for the two weeks ending February 26, 2016, and overall, remains not far off the record wide of 1.9% reached in March 2015 [Figure 2]. For comparison, the 20-year average yield advantage of 10-year Treasuries to comparable German government bonds is only 0.5%.

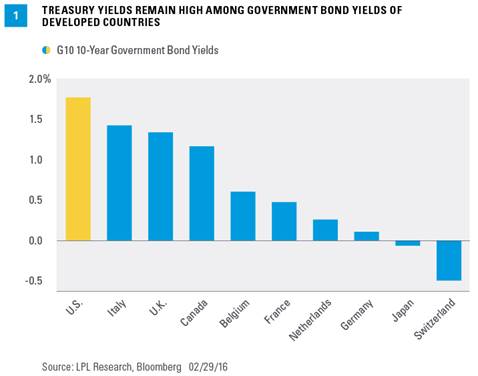

The rise in U.S. short-term yields since February 11, 2016, was driven by a rebound in Federal Reserve (Fed) rate hike expectations, even though market expectations remain very modest overall, and better domestic economic data, including higher than expected inflation readings. In Europe, however, economic data have faltered compared to the U.S. [Figure 3] and fueled expectations of additional stimulus, hence the widening yield differentials. Of course, the European Central Bank (ECB) and Bank of Japan (BOJ) are both undertaking large quantitative easing programs, which originally drove yield gaps between U.S. Treasuries and overseas government bond yields. Both the ECB and BOJ seem more likely to increase stimulus, rather than tighten policy, suggesting that yield gaps may remain wide and continue to support intermediate- and long-term Treasury prices.

CURRENCY DEVALUATION

Some central banks, including China’s, have pursued currency devaluation in an attempt to bolster their economies. In some cases, central banks have sold Treasuries in order to finance such policies, but the impacts have been little more than speed bumps for Treasuries. In both August 2015 and early January 2016, when anecdotal evidence of currency-related selling was apparent, Treasury prices were restrained, but only for a few days before increases resumed.