The absence of a federal budget and high levels of government debt reduce fiscal capacity. The lack of federal deposit insurance blunts the full pass-through of ECB monetary policy to member states. With growth stuck in low gear and rock-bottom policy rates, the eurozone is caught in a liquidity trap. Time will tell whether the ECB’s latest stimulus package is enough to get the eurozone out of this predicament or whether it simply is pushing on a string. Although its sobering inflation forecasts of 0.1% in 2016, 1.3% in 2017 and 1.6% in 2018 suggest more easing might be needed, what could the ECB still do, and will it work?

Monetary policy phases

Before considering what the ECB could still do, it helps to get orientated on where we came from and what history suggests the final destination could be. To do so, we divide monetary policy into a continuum of three phases: conventional, unconventional and monetisation.

• Conventional: policy rate changes, liquidity provision, reserve requirements

• Unconventional: negative interest rates, large-scale asset purchases

• Monetisation: full subordination to fiscal policy, helicopter money

To state the obvious: The ECB is in the unconventional phase. We concur with ECB President Mario Draghi’s statements at the 10 March press conference that its scope to cut interest rates further is limited. The benefits of even lower negative rates are declining and the costs are rising. In Draghi’s words, “[Can we] go as negative as we want without having any consequences on the banking system? The answer is no.” Interest rates below -0.5% could ultimately be counterproductive, in our opinion, for three reasons.

Financial stability. Negative interest rates reduce banks’ profitability because they lower net interest income. Interest income falls because banks typically pay zero interest on retail deposits while paying the central bank on excess reserves and earning less interest on their overall loan book. The central bank’s negative interest rate confronts commercial banks with a dilemma. Doing nothing impairs their profitability, with consequences for the cost of equity capital and wholesale funding. Yet banks cannot pass on negative interest rates to retail customers, who can redeem deposits for cash yielding zero, for risk of triggering a run on deposits.

Bank margins. Negative interest rates force banks to cut costs, raise revenues or find other ways to remain viable. One way is to raise interest rates on loans and mortgages. Paradoxically, negative interest rates might lead to higher borrowing costs for consumers and businesses. Sweden’s Riksbank and the Swiss National Bank cut their policy rates to -0.5% and -0.75%, respectively, yet banks in these countries increased mortgage lending rates relative to the policy rate to improve profitability.

Currency depreciation. Negative rates work like currency intervention in disguise, which taken globally, is a zero sum game. By not passing negative interest rates on to retail customers, banks shelter households’ savings and consumption behaviour from the incentives of paying to save. Banks pass negative interest rates on to wholesale lenders, however, who cannot hoard large quantities of notes. Negative wholesale money market interest rates place downward pressure on the external value of a currency. In large, open economies, negative interest rates export the central bank’s deflationary problem abroad via currency depreciation.

With the interest rate on its deposit facility at -0.4%, the ECB has effectively exhausted interest rate policy. It could cut the interest rate on the main refinancing operation, currently zero percent, a bit further, but if more stimulus were needed, we think it will have to expand asset purchases instead.

Obliged to be unconventional: credit easing

By adding corporate bonds to the list of government, agency and covered bonds as well as asset-backed securities that it is purchasing, the ECB is firmly in the realm of credit easing. As we gain experience with large-scale asset purchases (LSAP) – quantitative easing using government bonds and credit easing using private sector securities – we see two aspects that suggest they too have a declining marginal efficacy.

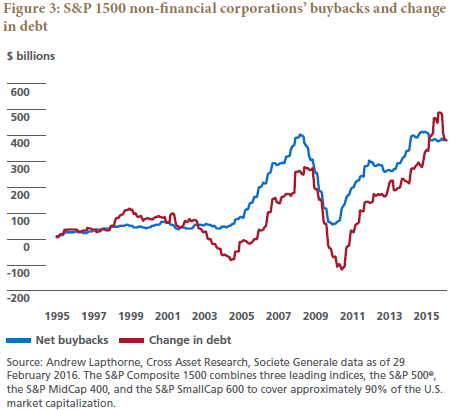

The first is the weak investment since the financial crisis. The most likely counterfactual to what would have happened without LSAP is a depression; however, LSAP might simply be laying the foundation of the next bubble by stimulating financial investment instead of investment in the real economy. Andrew Lapthorne at Societe Generale points out that companies in the U.S. have borrowed to finance stock buybacks, particularly since 2011, rather than invest in the real economy (see Figure 3). Stock markets may become vulnerable once the monetary stimulus has been taken away.

The second is that despite LSAP, risk premia can still increase when fundamentals or technical market flows dominate, as the experience in the first two months of this year suggests. We think the limited extent to which LSAP can compress credit and equity risk premia through purchases of government bonds relates to the inelasticity of demand for high quality, perceived safe assets. As many of our clients know, there are limits to how much risk – term, credit and equity – investors are prepared to take.

An Ugly Deleveraging

March 23, 2016

« Previous Article

| Next Article »

Login in order to post a comment