While many investors have expanded their risk limits in response to low yields, risk budgets still exist. Once reached, the known loss on low or negative-yielding government bonds might be preferable for some investors to the potentially unknown loss, or gain, on riskier assets, particularly if the central bank’s purchases drive the valuation of assets away from fair value. In other words, once the most elastic investors have sold out to the central bank, LSAP could also end up pushing on a string.

Although we acknowledge the marginal efficacy of monetary policy is declining, we disagree with the view the ECB has run out of ammunition. There remains a large amount of assets outstanding that the ECB could theoretically purchase. And now that it has started with non-financial corporate bonds, blue-chip equities may not be far away.

To sustainably suppress credit and equity risk premia, however, we believe the ECB would have to buy similarly large quantities of corporate bonds and equities as it has of government bonds. To be clear, this is not our forecast, but were more easing needed in the future, we think this is the route unconventional monetary policy would take.

In their basic form, unsterilised purchases of assets are a modern version of ancient rulers debasing their currency. LSAP of government bonds enables a government to finance the budget deficit. The line between a central bank buying newly issued government bonds in the secondary market or direct from the government is very fine, yet critical, to whether the activity is monetisation or not. In the extreme, does it really matter whether LSAP of government bonds occur in the secondary market or not?

You don’t want to go there: monetisation

Should unconventional monetary policy fail to pull countries out of the liquidity trap, the risk governments remove central bank independence and use monetary policy to directly finance budget deficits is not to be underrated.

If economies remain stuck in a liquidity trap, for example, the amount of LSAP needed to sustainably achieve a 2% inflation target might be so large that the boundary between indirect and direct financing of the budget deficit is indistinguishable. And once on that slippery slope, explicit monetisation of the budget deficit – such as a direct line of credit between the central bank and the government – may not be far away.

The temptation to monetise might be most acute in societies with aging populations, high debt burdens and low productivity growth. Such societies face a tough choice: structural reforms, like upgrading judicial and education systems and liberalising markets, or tinkering with central bank independence.

Structural reforms are critical for long-term potential growth; however, they tend to increase competition in the short term, which does not help inflation return toward target. Even if governments embrace reforms, central banks’ inflation mandates oblige them to take action in some way. In those societies unwilling to embrace reforms and incapable of generating growth endogenously, central bank independence might come under threat.

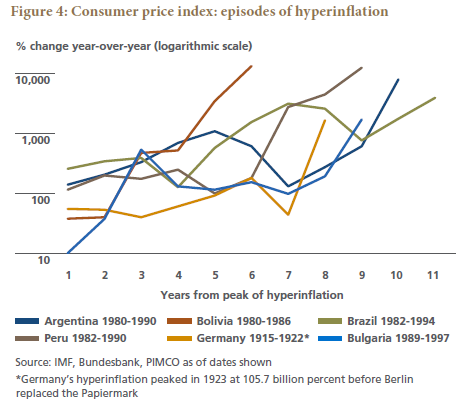

Monetisation is not something investors should wish for. We are unaware of any country that did “just a little bit” of monetisation without creating “a lot” of inflation; it’s hard to put the inflation genie back in the monetisation bottle. From 1795 in France to 2007 in Zimbabwe, financial history has witnessed 56 episodes where budget deficits financed by the monetary authority produced hyperinflation. The turning point from price stability to hyperinflation was often short and nonlinear (see Figure 4), suggesting once started, it’s very hard to stop. For example, Germany’s consumer price inflation averaged 1.9% from 1900 to 1914 before jumping to 169% on average between 1915 and 1922.

Andrew Bosomworth is head of PIMCO portfolio management in Germany.

What about Europe today? Article 123 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union prohibits monetisation, and despite critics in Germany, Draghi pointed out on 10 March that “We [the ECB] haven’t really thought or talked about helicopter money.” Investors, in Europe at least, should not fear resurgent inflation.

Investment implications

Eurozone growth and inflation will likely remain low. We see few signs governments are willing to address growth’s secular headwinds with structural reforms. The marginal efficacy of monetary policy is declining. The ECB is probably done with cutting interest rates, but expect it to expand LSAP beyond corporate bonds and into stocks, if needed. Bond yields will likely remain low too. Ten-year German Bunds currently yielding about 25 basis points may no longer offer a moderate-yielding diversifying hedge for risky assets, like stocks. Investors seeking high-quality government bonds for diversification purposes may have to look to currency-hedged alternatives, such as U.S. Treasuries, to play this role.

To achieve their return targets, investors may have to make structurally larger allocations to higher-yielding corporate and emerging market bonds. But there is no free lunch. So long as growth remains low and inflation fails to respond to unconventional monetary policy, bail-ins and haircuts will likely play a larger role in reducing unsustainable debt burdens in the future. Europe’s Bank Recovery and Resolution Directive merely formalises this process. Active credit selection will therefore become more important than ever. The ECB’s credit easing helps to soothe debt burdens, but without governments also helping the ECB to boost growth, it will be an ugly deleveraging.