Key Points

• We are monitoring three indicators to gauge the effectiveness of central bank efforts to stimulate economic growth: loan rates, loan demand and the extent to which fiscal policy helps or harms monetary policy.

• Although central banks are not yet out of ammunition, their new weapons, such as paying eurozone banks to make loans, have unknown risks compared with traditional monetary policy.

• Market volatility is likely to continue as sluggish global growth and already-low interest rates create ongoing challenges for central banks.

Are central banks running out of options they can use to stimulate economic growth? Markets may be wondering after recent moves by the European and Japanese central banks fell short of expectations.

Until recently, interest rate cuts by central banks weakened local currencies and boosted stocks. However, that dynamic no longer appears to be working. The yen actually rose after the Bank of Japan (BoJ) said in late January it would adopt negative interest rates. And the euro was unchanged after the European Central Bank (ECB) announced a "kitchen sink" of measures that included dipping further into negative-interest-rate territory in March.

Central banks in almost a quarter of the global economy have adopted negative interest rate policies (NIRP). The hope is that charging banks for the reserves they keep with the central bank will encourage them to lend more, thereby stimulating growth. The problem is that NIRP may actually hurt lending, as we'll see below.

So where does that leave central banks? We think they can still help drive growth, but the types of policies they adopt matter. We are monitoring three indicators to gauge if central banks are reaching the limits of effectiveness: loan rates, loan demand and the extent to which fiscal policy helps or harms monetary policy.

1) Loan rates: banks may make loans more costly

The problem with negative interest rates is that it cuts into banks' profit margins. When the central bank effectively levies a fee on reserves, banks can either eat that expense and lose money or pass it on to their customers. Passing it on to savers raises the risk that people will simply withdraw their money—why keep a savings account if it costs you money? The other approach is to pass the cost onto borrowers by raising rates. Of course, making loans more costly can hurt demand, thereby cancelling any stimulus effect from negative interest rates.

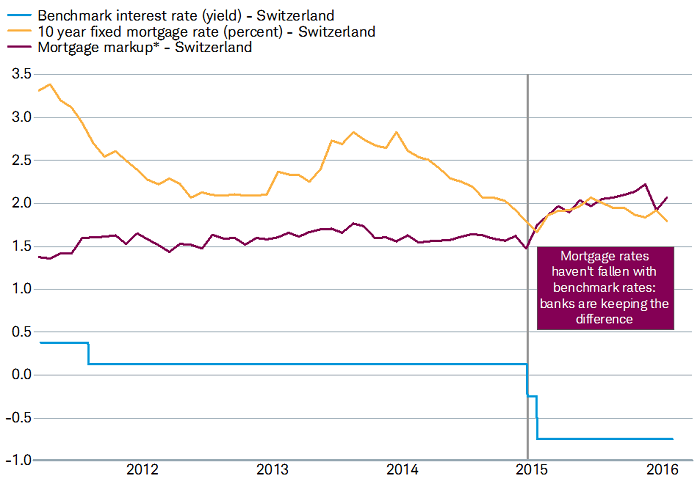

This appears to be happening in some countries. After Switzerland adopted NIRP at the beginning of 2015, banks raised mortgage rates, resulting in a bigger markup, or the difference relative to 10-year government bond yields. By the fourth quarter, growth in mortgage debt had dropped to its slowest pace since 2008.

Swiss mortgage rates haven't fallen despite rate cuts

Source: Charles Schwab & Co. Inc., FactSet, Bloomberg, Swiss National Bank, as of 1/29/2016. *Mortgage markup is the difference between the 10-year mortgage fixed rate and the 10-year government bond yield.

Fortunately, there are ways to counteract such moves. For example, the ECB's new targeted longer-term refinancing operations (TLTRO) allow banks that qualify to get paid to borrow from the ECB to make new loans. This helps reduce the hit to bank profit margins from NIRP, and may keep banks from having to raise lending rates or cut back on lending.

Rather than cutting benchmark rates further into negative territory, central banks seeking to deploy more stimulus may consider measures that limit the impact of NIRP on the financial sector to make sure their policies have the desired effect.

2) Loan demand: borrowing and optimism

Lending is the lifeblood of economic growth, as it can create a virtuous cycle of growth. When businesses take out loans to expand operations or consumers borrow to make purchases, companies that receive this money can use it to pay workers or create jobs. That tends to boost consumer spending and increase business revenue, which can then be used for further investment or hiring, and so on.

That's one of the reasons central banks try to influence borrowing decisions with their monetary policy. But what happens if borrowers don't respond, either because they already have too much debt or are not confident in the future? That can be bad for growth.

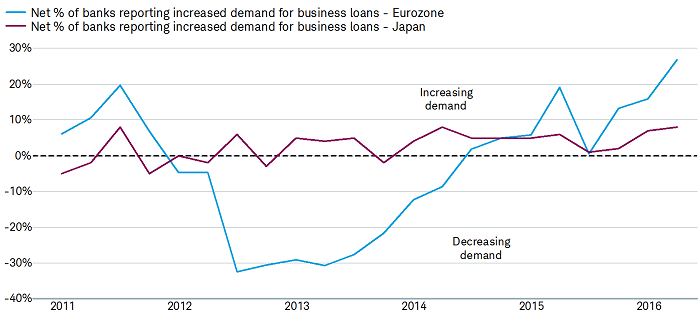

Corporate demand for loans continues to be healthy

Source: Charles Schwab & Co. Inc., European Central Bank, and Bank of Japan, as of 3/15/2016.

Fortunately, the picture isn't totally bleak. We are encouraged that demand for loans continues to rise in Europe and Japan, the two main economies at the center of the NIRP concerns. That suggests a certain optimism about what lies ahead and that initial rounds of monetary stimulus are still working. However, if potential borrowers become more cautious and pull back, there may be little central banks can do to drive growth.

3) Fiscal policy: the problem with austerity

Monetary policy has been the primary form of economic stimulus since the global financial crisis. What about government spending? Unfortunately, some governments have gone against the direction of central banks' monetary loosening by cutting spending and raising taxes, citing concerns about their long-term solvency.

Until recently, these fiscal moves have acted as on a drag on growth. Things are starting to look a little better, though: Growth in Europe and Japan has improved from its pace between 2011 and 2014.1 And that fiscal drag actually turned to slight fiscal stimulus over the past year, which could finally help support monetary stimulus. Nevertheless, many governments hesitate to enact more potent fiscal stimulus because of slumping revenue growth or high debt burdens.

If governments return to austerity, that would work against all the efforts being made on the monetary front. Fiscal policy is a matter of governments, not central banks, so a decision to clamp down on spending wouldn't necessarily leave central banks without ammunition to stimulate growth. But it would mean they were shooting blanks as growth slowed.

Conclusion

While monetary policy has become more difficult with interest rates at or below zero, we believe central bankers are not yet out of options. Still, some policy moves could end up hurting rather than stimulating economic growth, so central banks need to proceed carefully. As central bankers get more creative in trying to revive growth they could invite unknown risks. Paying eurozone banks to make loans could result in loans made with less regard for fundamentals, while negative rates on deposits could result in savers hoarding money.

The combination of sluggish global growth and already low interest rates is likely to create continued tests for central banks and market volatility in 2016. We continue to recommend a globally diversified asset allocation to manage this volatility.

1. Bloomberg, 3/2016.

Michelle Gibley is director of international research at the Schwab Center for Financial Research.

Read more here.