With expanding sovereign credit needs colliding with slow private sector growth, volatile stock markets and low bond yields, investors are taking the view that they need more than asset allocation to be successful.

This would appear to mean that hedge funds, particularly funds of hedge funds, will remain key investment vehicles for institutions and qualified individual investors.

More flexible than traditional investment vehicles, hedge funds can navigate difficult markets by shorting stocks and bonds. They also provide exposure to interest rate fluctuations and foreign exchange markets and can profit from low-risk merger arbitrage. A fund of funds (FoF) hedge fund strategy-with an added layer of oversight and more diversification than a single-fund approach-may be expected to produce even more consistent, less-volatile returns.

"Many individual hedge funds are not really hedged against risk," says Leo Marzen, partner at New York-based Bridgewater Advisors, with $850 million in assets under management. "One is more likely to gain such protection when one is in a fund of funds, whose pieces have been assembled to produce consistent performance."

Yet when you dig deeper and look at actual performance, FoFs have neither cut risk nor delivered superior returns in the short, medium or long run. Recent history also shows that some FoF managers have failed-sometimes in miserable fashion-to perform proper oversight.

Madoff Epiphany

Bernie Madoff certainly wasn't the first hedge fund thief, but it is difficult to find a more nefarious example. The fact that he made it into so many funds of funds made matters worse. How could Madoff have fooled so many sophisticated investors? What kind of due diligence are investors actually receiving for the additional layer of expense created by a fund of funds manager? (FoF managers typically charge a 1% annual management fee and a 10% performance bonus. This is on top of individual hedge fund manager expenses that are usually 2%/20%.)

Many financial advisors say the Madoff scandal actually emphasizes the need to go the FoF route. Funds of funds that get burned by poor fund choices may suffer asset withdrawals, which could exacerbate losses during a down market, concedes Michael Mattise, chief investment officer of Philadelphia-based Radnor Financial Advisors, with $850 million in assets. But he believes FoFs are better able than individual funds to withstand such a crisis. One need only look at the fate of individual investors who were exclusively in Madoff's fund to appreciate the value of a multi-fund approach.

Like many advisors, Mattise generally recommends that qualified investors have 12% to 15% exposure to hedge funds, which he achieves primarily through funds of funds. Over the eight years in which he has been providing clients with hedge FoFs, he has generally been pleased with the risk-adjusted returns. "Returns have been better than cash and fixed income," he observes. "Funds of funds provide us with returns that are uncorrelated to the market, which is very important for the overall portfolio."

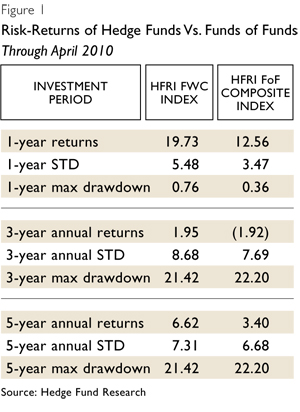

But according to Hedge Fund Research, the Chicago-based industry data tracker, over the past 12 months through April, the average individual hedge fund gained 19.73% while the average fund of funds gained 12.56%. Over the last three years, hedge funds gained an average of 1.95% annually while the average fund of funds lost 1.92%.

The results are pretty much the same going back five years: Individual funds gained an average of 6.62% annually, outpacing funds of funds by 322 basis points a year.

By one measure, funds of funds appear less volatile than hedge funds. Over the three trailing time periods, the annualized standard deviation of funds of funds is consistently lower than that of individual funds.

But another measure of risk tells a different story. Maximum drawdown-the largest decline during a downturn before a fund or FoF reclaims a former high-is slightly larger for funds of funds over the trailing three- and five-year periods. The market collapse that bottomed in early 2009 is the worst such drawdown for both periods: 22.20% for funds of funds versus 21.42% for individual hedge funds.

Advocates of funds of funds may argue that these conclusions have been skewed by a historic few months. But Sol Waksman, the founder and director of BarclayHedge, another prominent data tracker, says that it would be wrong to eliminate the late 2008/early 2009 time period as an outlier. By the same token, the performance gap was unusual, he notes. In 2009, individual hedge funds returned more than 21.5% while the average fund of funds gained only 9.4%. "Occasionally, funds of funds significantly underperform the industry," he says. 5% or 10% deviation in a given year does happen."

Yet Waksman thinks the risk of an individual fund blowup-due to fraud, a rogue trader, misjudged risk or significant strategy drift-is reason enough to find safe haven in a multi-fund strategy. "Most investors don't have sufficient capital to diversify across a series of individual hedge funds to protect themselves from a meltdown," says Waksman. "So I think investors would be wiser to give up some performance in exchange for the security of multi-fund exposure."

A Remarkably Lousy Year

Why did funds of funds underperform so badly in 2009? Should the reasons still be a concern?

First, some FoFs found themselves locked into underlying funds that either restricted redemptions or kept substantial portions of illiquid investments locked up in so-called "side pockets" that couldn't be sold to meet redemptions. Not having access to all their capital prevented fund of funds managers from rotating into strategies that were rebounding in 2009.

Second, there may have been some reluctance by FoF managers to jump aggressively back into the market after having failed to protect assets in 2008, observes Kristoffer Houlihan, director of risk management at Pacific Alternative Asset Management Company, a fund of funds manager with $9 billion in assets. (The average fund of hedge funds lost 22.18% in 2008, underperforming the average individual hedge fund by 55 basis points.)

Third, funds of funds experienced the worst net asset flow in their 20-year history in 2009, with more than $118 billion leaving the industry, according to HFR. This made it more difficult for fund of funds managers to invest and exploit the rally.

Fourth, but as important as any other factor, there was a significant reduction in leverage. FoF managers typically employ leverage to boost returns and cover their additional expenses. In the area of asset-backed loans-a traditionally profitable, low-risk strategy-the sudden elimination of leverage froze nearly all funds of funds focused on this strategy.

Funds of funds that utilized asset-backed loans were forced to return billions of dollars to banks who pulled their leverage during the credit crisis by redeeming shares in underlying funds, says Jonathan Kanterman, managing director at Stillwater Capital Partners. This transformed a patient medium-term strategy into something it was not-a short-term trade. Without sufficient liquidity to meet rising investor redemptions, more than 150 of these funds were forced to gate, temporarily suspend or wind down their operations.

Citing data from HedgeFund.net, Kanterman believes FoF leverage has dropped from a 2008 peak of around 80% of net assets to now under 40%.

Transparency

Many issues affecting fund of funds performance were compounded by insufficient transparency. This prevented many managers from truly knowing their composite risk by sector, asset class, currency, leverage and duration, and how the addition and deletion of individual funds were affecting these risks.

Ron Papanek, head of business strategy at RiskMetrics, a leading hedge fund aggregator of portfolio-level data, says there is a clear need for an improved understanding of investment concentration and the risks associated with FoF portfolios. At the same time, he says, hedge fund managers are increasingly aware of the need to make their individual portfolios transparent to investors.

According to Nicholas Verwilghen, the partner overseeing risk management at the Switzerland-based fund of funds EIM-a $8.5 billion global manager that customizes multi-fund programs for over 100 institutional investors-the percent of his underlying funds that have agreed to provide this information has jumped over the past year from 50% to 100%. They do so through an independent third party that verifies and aggregates the data.

On the operational side, the 2008 meltdown also emphasized the need for independent and full-service, third-party administrators to ensure accurate pricing and trade information, and independent custodians to ensure the legitimacy of assets.

"These improvements are significantly improving the assessment of portfolio exposure and concentration, counterparty, liquidity, credit and manager balance sheet risks," Verwilghen says.

Kenneth Phillips, founder and CEO of Santa Monica, Calif.-based HedgeMark, which analyzes and integrates hedge fund portfolios and risk management systems, is less sanguine about industry prospects. He believes FoF managers rely too much on modern portfolio theory.

He sees two problems in doing this: MPT requires the use of a reliable and relevant benchmark, which Phillips believes does not exist for FoFs because hedge funds are a mix of various strategies and leverage that cannot be meaningfully averaged together. Also, funds of funds seek greater diversity across individual funds and investment platforms that don't always provide sufficient transparency, preventing thorough portfolio analysis.

Phillips believes funds of hedge funds should use managed accounts as underlying funds to ensure full transparency, asset control and manager accountability. This enables a FoF manager to apply a comprehensive risk management overlay to protect the entire portfolio.

"This approach is still far from the norm, but it should be to ensure investment mandates are met and fiduciary standards sustained," Phillips says.