Cash holdings in investment portfolios are at record highs, and the rationales for these allocations are remarkably diverse. Some investors seek to wait out market volatility, while others have strategically increased cash allocations to reduce portfolio risk. Many are “barbelling” higher-yielding, volatile core assets with lower-volatility, income-producing short-term fixed income strategies. Still others are seeking to optimize returns on cash before U.S. money market reform takes effect later this year.

At the same time, two profound market dynamics are at play: First, 2a-7 money market funds continue to yield next to nothing due to a multitude of influences, including supply constraints, more demand and the forthcoming regulatory reforms; second, investors ‒ ranging from individuals to large institutions ‒ are increasingly deploying ETFs in their investment portfolios due to their transparency and operational ease of use.

The question many investors are asking now is how can ETFs be used for liquidity and volatility management given these evolutionary market changes? Here are some of the important considerations and why PIMCO’s actively managed short-term ETFs, MINT and LDUR, may be superior tools for liquidity management.

‘Capital preservation’ does not necessarily maintain purchasing power

In today’s environment, many investors are seeking “safety” by allocating to money market funds, which are expected to return capital because of their stable net asset value (NAV). Similarly, many ETF investors have chosen U.S. Treasury-bill funds both for their low total expense ratios and the perceived safety of index T-bill exposure.

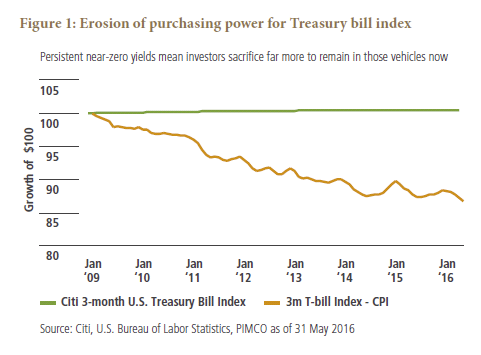

However, preserving capital does not equal preserving purchasing power ‒ essentially, returns after inflation. Figure 1 looks at the decline in purchasing power of T-bill index returns in the low inflation environment since the financial crisis of 2008. The same holds for money market funds: For much of the past 40 years, traditional money market funds have provided investors with positive inflation-adjusted returns, but in today’s low yield environment, that is no longer the case. In more normalized, higher-inflation environments, the erosion of purchasing power could be even greater.

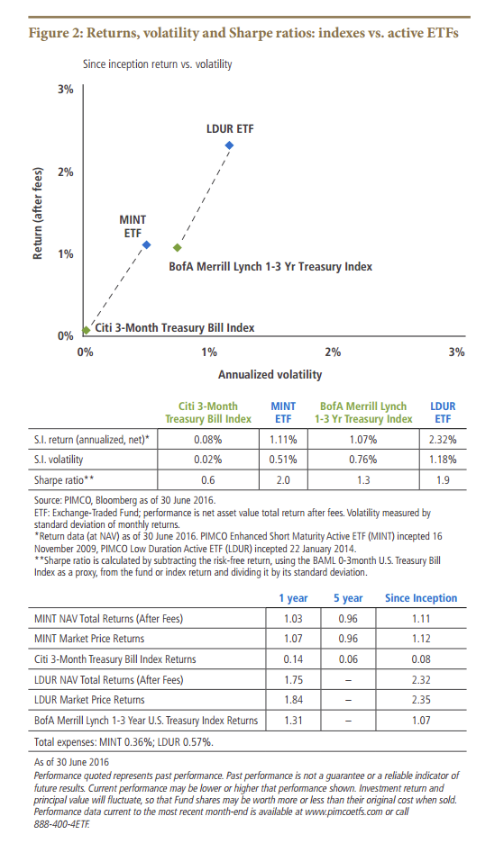

Active short-term management strategies can potentially remedy this deficit because they seek not only return of nominal capital but also additional income, which can help protect purchasing power. When considering cash strategy alternatives, liquidity and capital preservation are important, but they are not the only considerations. It is also important to look at the risk, or volatility, for a given level of return. One measure of this is the Sharpe ratio, which is calculated by taking the average return earned in excess of the “risk-free” rate, typically represented by T-bill returns. The greater the Sharpe ratio, the more attractive the risk-adjusted return.

Figure 2 shows the returns, volatility and Sharpe ratios of the PIMCO Enhanced Short-Maturity Active ETF (ticker: MINT) and the PIMCO Low Duration Active ETF (ticker: LDUR), along with those of the Citi 3-Month Treasury Bill Index and the Bank of America Merrill Lynch 1-3 year U.S. Treasury Index.

The data in Figure 2 illustrate important issues. First, for investors seeking capital preservation, ETFs that track T-bill and even short maturity indexes may not adequately compensate investors for the risks they take, even though they may be low-cost. Second, the after-fee, risk-adjusted returns of active ETFs may better protect purchasing power.

Getting active, going global and diversifying to reduce volatility and improve liquidity

Short maturity active ETFs can employ several levers for helping reduce risks and enhance returns. Active management generally increases an ETF manager’s freedom to navigate volatile markets. Namely, active managers can utilize a wide opportunity set:

Multiple sectors, and the ability to adjust exposures as market conditions and manager views change, offer key advantages. Most index ETFs used for liquidity management provide exposure to one or two sectors of the market, such as Treasuries or investment grade credit, and usually only the U.S. bond market. They maintain a static, structural exposure to interest rates (duration), which can potentially result in lower performance as rate expectations adjust. Unlike active ETFs, index funds only adjust exposures when the index changes. This leads to forced “buying and holding,” as well as forced selling when market conditions might warrant just the opposite.

A global opportunity set. Of the roughly $100 trillion in global bonds, the U.S. market represents only about one-third of the existing inventory and U.S. T-bills less than 2% of the total, or about $1.6 trillion. T-bills outstanding have declined by about $600 billion since the financial crisis, yet new requirements under money market reform are leading many asset managers to create government-only funds, further reducing supply of T-bills.

Alternative weightings and out-of-index securities. The largest bond index ETFs are market-capitalization weighted: They base the size of their exposure to any given security on how much is outstanding relative to other securities. Thus, index ETFs have the largest exposures to the most indebted borrowers or sectors. They also have limited ability to hold securities that are not in the index (typically 20% of the fund), which can potentially limit their diversification.

As one of the biggest and most experienced bond managers, PIMCO is positioned to take advantage of these levers. The short-term and funding desk at PIMCO manages about $300 billion in cash and short duration strategies globally, including MINT, the largest actively managed ETF, and LDUR, which represents an additional step out on the risk/return spectrum. The short-term desk draws on PIMCO’s time-tested investment process, including the firm’s top-down macroeconomic outlook and bottom-up sector and security selection from over 50 credit analysts worldwide. This is an experienced team of more than 10 portfolio managers who have managed cash and liquidity globally through many market cycles and macroeconomic environments, including the challenges of 2008. The team most recently won Morningstar’s U.S. Fixed Income Fund Manager of the Year award for 2015.

Implementing an ETF as an alternative to cash solution

Consider the holding period

When thinking about how to strategically manage cash and portfolio liquidity, the important considerations are how much cash is needed? What is the purpose of the cash holding (which drives the likely holding period and the risk tolerance)? And finally, what are the risk and return characteristics of potential cash and alternative cash solutions?

Consider, for example, a financial advisor who is helping a client and has identified three possible cash needs: a reserve to cover six months of household expenses, the purchase of a new car in one year, and the down payment for a home in two to three years. The client has a moderate risk tolerance, and the timing of the car and the home purchases could be pushed back.

How might this investor think about managing cash?

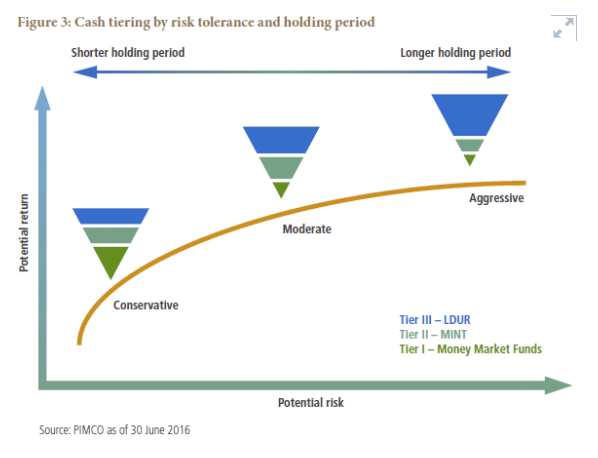

Tier cash to maximize return potential for given risk tolerance

A potential solution is to tier the allocation into cash and alternative cash investments using money market funds and active short-term ETFs such as MINT and LDUR. Money market funds* may be well suited to immediate cash needs, while cash alternatives like MINT could be considered for holding periods in excess of three months. MINT seeks to provide a stable, although not constant dollar, NAV and additional income in the form of monthly distributions and has been used extensively for liquidity management. LDUR can be added to a tiered liquidity portfolio and used to help grow portfolio balances over a longer time horizon, generally more than a year; LDUR has core bond characteristics and thus an incrementally higher risk/return profile than MINT.

In the example above, the funds needed to buy a home could be invested in LDUR while those needed for a new car as well as a portion of the reserve for household expenses could be invested in MINT. The balance of the reserve for expenses would likely need to be in a money market fund. The relative size of these three investments could be adjusted as the time approaches for purchasing the car and the home. In other words, the portfolio can be rebalanced between these three investments, bringing the overall portfolio down to a lower risk/return target as the need for cash becomes more immediate.

Figure 3 illustrates cash tiering by risk tolerance, showing the change in allocation as holding periods decrease.

Tiering cash attempts to better align the risk and return characteristics of cash and alternative cash assets with the holding period and risk tolerance of investors to preserve purchasing power and enhance risk-adjusted return.

Jerome M. Schneider is a managing director PIMCO, Newport Beach office and head of the short-term and funding desk.

Natalie Zahradnik is an executive vice president in the Newport Beach office of PIMCO, an exchange-traded fund (ETF) strategist and a member of PIMCO's global wealth management team.