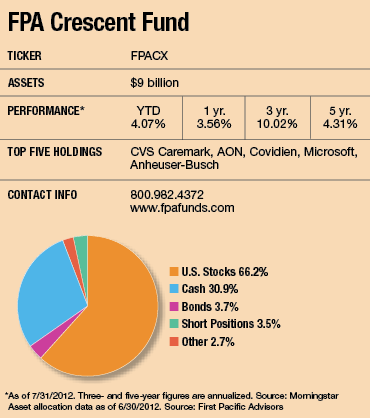

Steve Romick's description of his $9 billion fund as a "free-range chicken" may seem a bit odd, but long-term investors probably aren't bothered by it.

The FPA Crescent Fund, which Romick has managed since 1993, sheds the traditional confines of the mutual fund style cage by scavenging for bargains among a wide variety of investments. He can invest in any size stock based anywhere in the world, shift assets into high yield and distressed debt, short stocks and even nibble at alternative investments such as bank loans.

"Value shows up in different places," he observes. "As long as an investment is liquid, why shouldn't we be able to take advantage of an opportunity?"

The fund's style is also notable for building up substantial amounts of cash if buying opportunities are scarce. At times, in the mid-2000s for instance, Romick has parked north of 40% of assets there.

Better Value In Large Caps

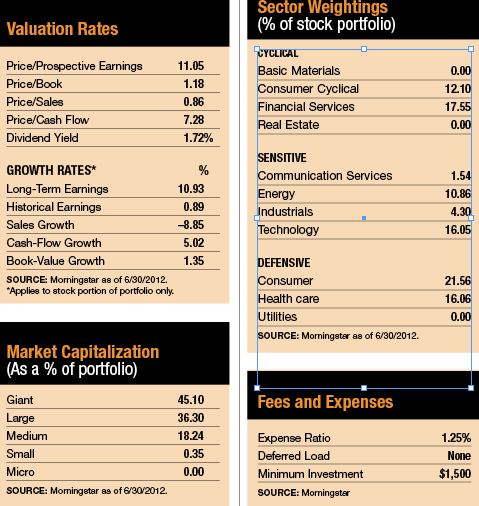

One of the most notable recent changes to the fund has been the size of the companies it focuses on. For most of its life, FPA Crescent mined mostly small-cap and mid-cap names for its stock sleeve, which usually accounts for at least 50% of assets. But over the last three years, it has migrated to larger blue chip names, which Romick believes are more attractively valued and better positioned to take advantage of growth in developing markets.

"Investors have bid up small-cap stocks to the point where they are trading at a premium to large company stocks," he says. "Yet growth prospects for small companies are no better than they are for larger ones."

As a result of the shift, the average weighted market capitalization of the fund's stocks is $31.4 billion, about five times higher than it was five years ago (though still well below the $110 billion weighted average market capitalization for stocks in the Standard & Poor's 500 index).

While the longer-term impact of the move to large caps remains to be seen, the eclectic and changing portfolio has fulfilled its manager's mission to provide equity-like returns with less volatility over the long term than the stock market. According to Morningstar, its performance has landed it in the top 2% over the last 10- and 15-year periods among its moderate target risk peers. But with its large cash allocation, the fund has missed out on some stock and bond market gains so far this year.

Beating the market over a few months or even a couple of years really isn't the point here, says Romick, a 49-year-old Los Angeles native. "We focus on results over a full market cycle of at least seven years," he says. "And we're not benchmark-conscious."

Morningstar analyst Christopher Davis notes that investors might also need to turn a blind eye to the benchmarks from time to time, since Romick's contrarian style and often cash-heavy portfolio means the fund will sometimes lag over short periods. The fund has outperformed over the long term more by preserving capital in down markets than by beating the markets in very bullish periods.

While Davis wonders if the fund's burgeoning asset base eventually could limit Romick's investment flexibility, he notes that the manager "still has plenty of room to employ his opportunistic approach-one he's executed deftly for nearly two decades." Romick says that there have been discussions at FPA about what asset level the fund would have to reach before the managers close it, but he would not disclose a specific number.

Before that happens, investors can still join the ranks of shareholders who have benefited from Romick's deep-value, go-anywhere style, developed in the mid-1980s while he was working for an investment partnership. At the time, an era of Wall Street greed and Predator's Balls, the high-yield bond market was riding high. Romick's appetite for the unloved was whetted a few years later when that market collapsed and many high-yield bonds began trading at extraordinarily deep discounts. "I looked at those distressed bonds and thought, 'Why not,'" he recalls of his decision to venture into a territory others avoided.

Three years after founding his own investment firm in 1990, he launched the Crescent Fund. After a number of discussions with First Pacific Advisors founder Robert Rodriguez, who also practiced a go-anywhere, value-driven philosophy, Romick moved his tiny $22 million fund to that firm in 1996.

When Financial Advisor conducted its last in-depth interview with Romick back in 2004, the then $458 million fund had 44% of its assets parked in cash because Romick wasn't finding any dramatically out-of-favor asset classes or industries that looked appealing. For the next few years, the fund's cash holdings regularly exceeded 40%, allowing it to soften the blow of a bear market that would devastate other funds.

With viable investment opportunities in short supply, FPA closed to new investors in 2005. By the time it reopened its doors in 2008, the bear market had created lots of buying opportunities for bargain hunters, so, with an ample cash war chest at his disposal, Romick scooped up deeply discounted high-yield bonds and distressed debt, securities that accounted for more than one-third of the portfolio by 2009. The decision paid off well after those bonds rebounded sharply that year.

A Dearth Of Bargains

Over the last couple of years, Romick has taken profits on most of those junk bond positions and put the money into the stock market. Today, the fund has two-thirds of its assets in stocks-more than double the weight it had in 2007 and near the high end of its historical allocation range. By contrast, the fund has less than 4% of its assets in bonds, a level close to its historic low.

"It's a seller's market for bonds right now," he says. "Companies are taking advantage of low yields by issuing debt. That's good for them as companies, but not so good for me as an investor." He's also concerned about the impact that inflation and rising interest rates would have on prices. Although inflation is well under control now, he believes that this could change if housing or auto sales rebound.

"I wouldn't say bonds are overvalued, but at current prices they do lack that margin of safety we're looking for. We're in the business of buying things at a discount, and we're not seeing many bargains in the bond market," he says.

At the same time, he isn't finding large swaths of value in any particular sector, and he finds stocks "neither particularly cheap nor particularly expensive." Given that tepid view, it's not surprising that the fund has about 30% of its assets in cash equivalents.

Romick believes that slower-than-expected economic growth in developed economies could eventually bring prices down to more appealing levels. "We do not believe the markets have priced such expectations adequately," he warned in his most recent letter to shareholders. "The United States is a bigger ship now than it was 50 years ago, and it just won't move as fast-especially since consumers have maxed out their balance sheets and governments are in the process of maxing out theirs. We've already had the secular benefit of households shifting from one to two incomes. Interest rates have already declined to generational lows."

Still, he is managing to find some attractive values in individual stocks, particularly larger blue chip names with strong sales to developing markets. Most of those holdings are based in the United States, though 21% are attributable to European companies such as French automaker Renault. Romick admits he isn't particularly fond of the company, whose sales depend heavily on European consumers. But because Renault's stakes in Daimler, Nissan and Volvo exceed the public value of its own shares, he believes that "the value that is being given away has less financial risk than in the past." He also favors WPP Group, an advertising agency based in the U.K. that has more than 2,500 offices in 108 countries. WPP has a global business, and about one-third of its revenues are coming from fast-growing markets outside Europe and the U.S. The stock also sells at a reasonable 10.5 times forward earnings.

He also likes companies with strong product niches, such as the fund's recent purchase, CareFusion, the leading medical technology company, which serves hospitals in the U.S. and abroad. The company's new management could improve research and development and help grow international sales at a faster clip than in the past.

The FPA Crescent Fund also has a smattering of alternative investments, including a stake in a private real estate investment trust that invests in farmland, which Romick views as protection against inflation and an opportunity to capitalize on rising food prices. He also dabbles in troubled loans from bank portfolios, which he purchases at a steep discount to their original value. Because he examines the borrowers closely and buys at prices that produce an expected 10%-plus rate of return, he believes the investments offer both limited downside and attractive returns.

Recently, he's been building a position in a senior note issued by a domestic energy company that is currently under financial stress. "Given the asset coverage of our claims, there appears to be low risk and reasonable upside in a restructuring," he says.