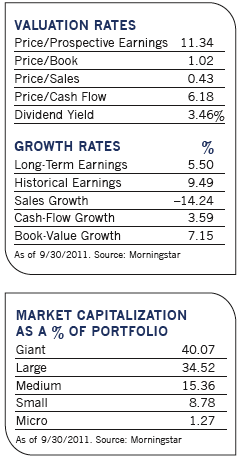

Buy stocks of companies whose public value is well below what a knowledgeable private buyer might pay. Focus on stocks with low price-to-book values, low price-to-earnings ratios and minimal debt. Hold on for five years or more. Repeat the process for 91 years.

If Tweedy, Browne Global Value Fund's investment recipe sounds like old school value investing, there's a reason for it. Back in the 1930s, firm founder Bill Tweedy became the primary broker for Benjamin Graham, the legendary father of value investing, in a business relationship that would span three decades. In the 1960s, another noted value investor, Warren Buffett, tapped Tweedy to execute trades for Berkshire Hathaway, then an ailing shirt manufacturer based in Massachusetts.

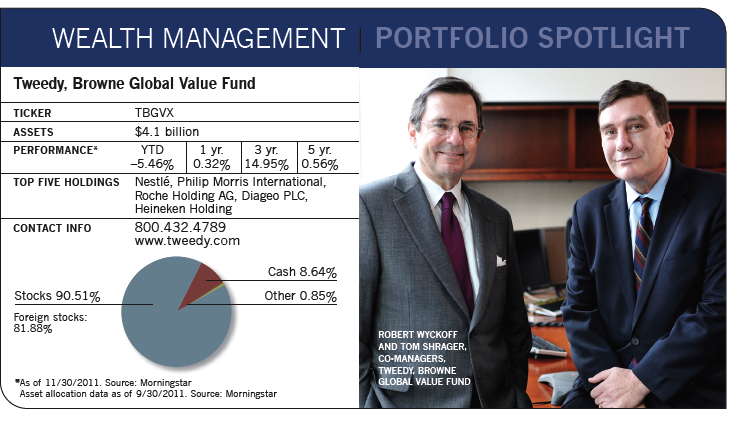

Judging from the performance of Tweedy, Browne's oldest fund, which turns 19 this year, managers William Browne, John Spears, Tom Shrager and Robert Wyckoff have carried on the value tradition with panache. From its inception in June 1993 through the beginning of November, a $10,000 investment in the fund would have grown to over $52,000, while it would have grown to only $23,000 in the MSCI EAFE Index. With a low portfolio turnover of around 10%, investors haven't had to sacrifice too much of those returns to capital gains taxes.

Some years have been better than others for the team of veteran managers, who have worked together for the last 25 years. Between 2002 and 2007, the fund landed in the bottom half of its Morningstar peer group as growth stocks flourished. But since 2008, a conservative strategy of focusing on dividend-paying companies with low debt and avoiding troubled European banks has helped the fund remain in the top tier among its Morningstar foreign large-cap value peers.

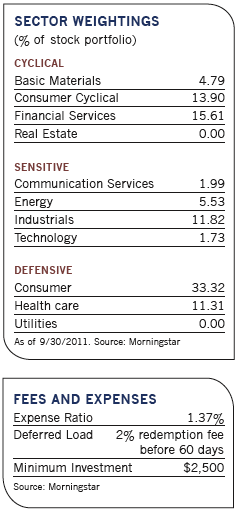

In 2011, a large swath of consumer staples stocks such as Coca-Cola, Unilever and British American Tobacco were the fund's strongest performers. These companies, which provide essential products or services, have continued to churn out consistent earnings in a recessionary environment.

While rising commodity prices could put a crimp on these companies' earnings by raising the cost of raw materials, Robert Wyckoff says the companies' large presence in emerging markets should more than offset those added costs. "Companies such as Unilever, Nestle and Diageo get one-third or more of the sales from emerging markets," he says. "They are growing revenue at a rate of 4% to 6% a year and doing quite well, given the challenging environment we are in."

Still, the managers have trimmed back some stocks, such as Mexican bottler Arca Continental, because they are trading close to the firm's estimate of intrinsic value. "But we still want to have a presence in them because we like the underlying businesses," says Wyckoff.

That's not the case for financial services firm Federated Investors. After the Federal Reserve announced it would keep short-term interest rates low until 2013, Tweedy, Browne sold out of Federated in the summer, believing the Fed's move would hurt the profitability of Federated's money market business. Tweedy, Browne also decided to take profits in Transatlantic Holdings after competing takeover offers bumped up the stock's price.

The fund replaced those holdings with new names such as U.K.-based Imperial Tobacco, the world's fourth-largest tobacco company. When the fund first began buying the stock in August, it was trading at roughly 11 times 2011 earnings and had a dividend yield of 4.3%.

"This company has no operations in the U.S., but it does have a couple of recognizable brand names in Europe and emerging markets," says Tom Shrager. "It has a significant presence in roll-your-own cigarettes, which is a cheaper way to smoke." Like British American Tobacco and Philip Morris, two other tobacco holdings, Imperial enjoys ample pricing power and steady demand, he adds.

Tweedy, Browne has also picked up some beaten down financial services stocks such as United Overseas Bank. One of the leading commercial banks in Singapore, it trades at approximately 10 times earnings and has a current dividend yield of around 4%. Bangkok Bank, another third-quarter addition, has more deposits than loans and is one of the safest banks around, Shrager says.

As oil prices declined in the third quarter, bringing down oil stocks, the team added to holdings ConocoPhillips, Royal Dutch Shell and Total. The last company, based in France, trades at about six times 2011 earnings and has a dividend yield of close to 7%. Wyckoff says it has a number of attractive production projects and has extensive experience working in some of the more politically challenging areas, such as Africa.

Newer holdings in the small and mid-cap part of the portfolio include Samchully, which distributes gas to homes and businesses in Korea. With the stock trading at 41% of the company's book value, it's a slow grower selling at a bargain price, says Shrager. Another inexpensive smaller company, Japan's Medikit, is a leading maker of medical products such as syringes and catheters.

Even though smaller company stocks account for nearly one-quarter of Tweedy, Browne's equity portfolio, the major emphasis is on companies with public values of $5 billion or more. That hasn't always been the case. Because the fund has the flexibility to invest across the market-cap spectrum, at times Morningstar has classified it as foreign small and mid-cap value. Today, it falls under the umbrella of the large-cap foreign value group.

"We go where the value is showing up, and right now that's in large company names," says Shrager. "Eight years ago, the better values were in small and mid-cap names, so that's where most of the portfolio was." Although there are some attractive smaller companies, he adds, the huge bounce-back of those stocks in 2009 and 2010 put many of them outside the fund's pricing comfort zone.

Even though the fund has the word "global" in its name and can invest anywhere in the world, it has never had more than 10% of its assets in the U.S. Currently, its U.S. allocation stands at a relatively modest 8%. "When we established the fund in 1993, our lawyers told us that using the word 'global' would give us the flexibility to invest in U.S. stocks. As it turns out, we've always managed to find attractive opportunities elsewhere," says Wyckoff.

"Elsewhere" usually means established markets in Europe and Japan, although the fund does dabble in a few emerging markets such as Mexico and South Korea. But China and Russia are off the table, at least for now.

"China is a managed economy with a communist government that has a hand in running public companies, and their policies aren't always in the best interests of shareholders," says Wyckoff. "As for Russia, there is a long-standing history of crony capitalism and government intervention in private company affairs."

To help control volatility and reduce risk, as well as ensure that performance rests solely on stock market returns, the managers hedge the portfolio back to the U.S. dollar. According to a study by the firm, currency fluctuations have historically been more pronounced than fluctuations in the stock market. In the 16 months between November 8, 2007 and March 10, 2009, for example, the U.S. dollar declined 35% against the British pound. Over the last 50 years, the Standard & Poor's 500 index has declined more than 20% in a year only four times, while major currencies have moved against the dollar much more frequently.

Given the bouncy market environment, eliminating volatility from currencies might not be a bad idea for some investors, says Wyckoff. For those who have a strong opinion about the direction of the U.S. dollar, or who use currency exposure for diversification, the firm also offers the unhedged Tweedy, Browne Worldwide High Dividend Yield Value Fund and the Tweedy, Browne Global Value Fund II-Currency Unhedged fund.

While the currency-agnostic managers don't have any opinions about the direction the dollar is likely to take in the coming year against the euro and other European currencies, they say a lot hinges on what happens in financially troubled countries such as Greece, Italy, Spain and Portugal. "If problems in those countries continue for a while, the euro would likely decline against the dollar and hedged portfolios would benefit," says Shrager. "On the other hand, unhedged portfolios would do better if those problems are solved quickly and the euro strengthens."

Wyckoff thinks there will be a slow, gradual resolution to the European debt crisis. "I think the problems in Greece and other troubled countries are going to drag on for quite some time," he says. "It's difficult to have a single currency without true fiscal unity, and it's going to take time to establish the framework for that to happen."