When the British public voted to exit the European Union a few months ago, James Hunt, who has managed the Tocqueville International Value Fund for over 15 years, wasn’t expecting that outcome. “I’d been in the U.K, just the week before the vote, and felt fairly sure things would go the other way,” he recalls.

International markets, especially those in Europe, reacted with a swift and sudden plunge before clawing back up in the following weeks. Instead of selling or standing pat and weathering the storm, as many investors did, Hunt used the downturn to add to some names in the portfolio that he felt got unjustly sucked into the market vortex.

His portfolio is laden with such temporary hard-luck stories. Recently, he purchased stock of a U.K. real estate company that’s been tarnished by dropping real estate values in that country, but has a strong balance sheet and excellent cash flow. (He won’t name it because it hasn’t been added to the fund’s public roster yet.) Over the last year or so, the sharp decline in oil prices has led him to scoop up bargains in companies that have been unfairly punished because of their perceived ties to the energy industry.

Such is the world of Hunt, who has been on the lookout for bad news bargains since he was an equity analyst in the mid-1980s at Delafield Asset Management, a well-known value shop. That firm’s founder, J. Dennis Delafield, co-manages the Delafield Fund, another Tocqueville offering. Since those early days, Hunt says he’s refined his approach by becoming more focused on the quality of a business, and more averse to corporate leverage.

His investment discipline focuses on buying good businesses, whether large or small, when they are temporarily out of favor or simply misunderstood. To make the cut, stocks must be selling at a discount of around 30% to intrinsic value, which he defines as what a strategic private buyer might pay for a business. The companies should also have defensible competitive advantages, shares trading at low multiples to free cash flow and low debt. “I like good businesses, with good balance sheets selling at great prices,” he observes.

He also pays attention to corporate governance, and insists on the presence of independent boards of directors and credible auditors. He won’t invest in companies located in countries with poor jurisprudence practices, such as Russia. And his distaste for high levels of corporate leverage means banks are often removed from the roster of portfolio companies.

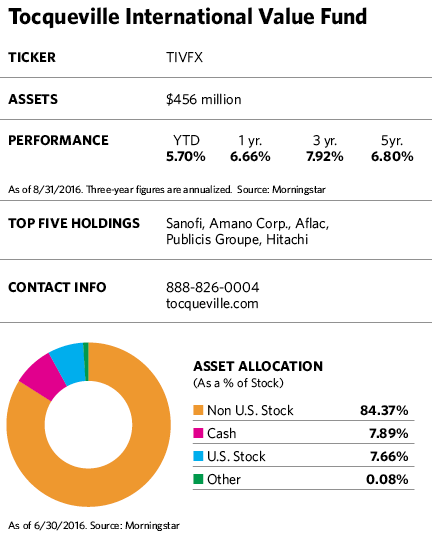

The strategy seems to be working. The fund has landed in the top 2% of its category over the last three years, the top 8% over five years, and the top 5% over the 10 years (periods ending July 31). Over the three years ending on that date, the fund’s upside/downside capture ratio against the MSCI ACWI ex-U.S. index was a laudable 101.14/67.92, while over five years it was 94.06/77.78.

Unlike many of its competitors, this all-cap offering has a meaningful presence in smaller companies. Nearly 31% of its portfolio is in small and mid-cap companies, according to Morningstar, while its benchmark has 8.53% in those companies and the foreign large blend category average is 12.2%. Regardless of company size, Hunt is a long-term investor with a three- to five-year time horizon for his investments. A team of 14 analysts, including four dedicated exclusively to the fund, help back his conviction.

With an active share of normally over 90% relative to the MSCI EAFE index, Hunt clearly takes a benchmark-agnostic, active approach to portfolio construction. He believes this makes his fund a good core international holding as well as “a strong complement to a passively managed or benchmark-focused international equity allocation.”

Although he focuses mainly on stock valuations and the corporate characteristics of his companies, he also keeps an eye trained on economic and market trends. It hasn’t escaped his notice that with the exception of a few flashes of glory, international markets have been underperforming the U.S. stock market for years. The upside, he says, is that stock market valuations abroad are much more compelling than they are in the U.S. And because foreign economies are in the earlier stages of recovery, the odds for profit upswings at foreign companies will be better once the recoveries finally take hold.

In some cases, external events have worked in favor of portfolio companies or created new buying opportunities. A weakening of the euro and yen, for example, makes export-oriented companies more competitive as revenue streams from the U.S. get a currency boost.