When the British public voted to exit the European Union a few months ago, James Hunt, who has managed the Tocqueville International Value Fund for over 15 years, wasn’t expecting that outcome. “I’d been in the U.K, just the week before the vote, and felt fairly sure things would go the other way,” he recalls.

International markets, especially those in Europe, reacted with a swift and sudden plunge before clawing back up in the following weeks. Instead of selling or standing pat and weathering the storm, as many investors did, Hunt used the downturn to add to some names in the portfolio that he felt got unjustly sucked into the market vortex.

His portfolio is laden with such temporary hard-luck stories. Recently, he purchased stock of a U.K. real estate company that’s been tarnished by dropping real estate values in that country, but has a strong balance sheet and excellent cash flow. (He won’t name it because it hasn’t been added to the fund’s public roster yet.) Over the last year or so, the sharp decline in oil prices has led him to scoop up bargains in companies that have been unfairly punished because of their perceived ties to the energy industry.

Such is the world of Hunt, who has been on the lookout for bad news bargains since he was an equity analyst in the mid-1980s at Delafield Asset Management, a well-known value shop. That firm’s founder, J. Dennis Delafield, co-manages the Delafield Fund, another Tocqueville offering. Since those early days, Hunt says he’s refined his approach by becoming more focused on the quality of a business, and more averse to corporate leverage.

His investment discipline focuses on buying good businesses, whether large or small, when they are temporarily out of favor or simply misunderstood. To make the cut, stocks must be selling at a discount of around 30% to intrinsic value, which he defines as what a strategic private buyer might pay for a business. The companies should also have defensible competitive advantages, shares trading at low multiples to free cash flow and low debt. “I like good businesses, with good balance sheets selling at great prices,” he observes.

He also pays attention to corporate governance, and insists on the presence of independent boards of directors and credible auditors. He won’t invest in companies located in countries with poor jurisprudence practices, such as Russia. And his distaste for high levels of corporate leverage means banks are often removed from the roster of portfolio companies.

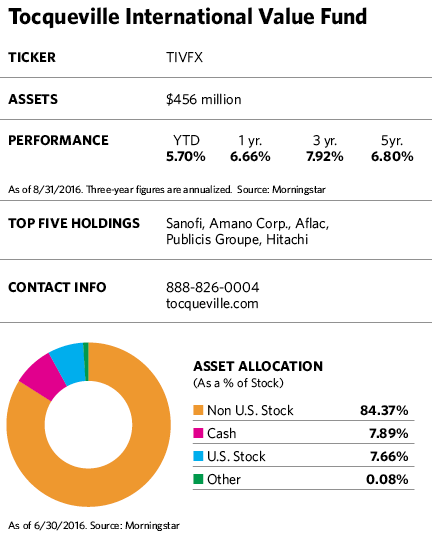

The strategy seems to be working. The fund has landed in the top 2% of its category over the last three years, the top 8% over five years, and the top 5% over the 10 years (periods ending July 31). Over the three years ending on that date, the fund’s upside/downside capture ratio against the MSCI ACWI ex-U.S. index was a laudable 101.14/67.92, while over five years it was 94.06/77.78.

Unlike many of its competitors, this all-cap offering has a meaningful presence in smaller companies. Nearly 31% of its portfolio is in small and mid-cap companies, according to Morningstar, while its benchmark has 8.53% in those companies and the foreign large blend category average is 12.2%. Regardless of company size, Hunt is a long-term investor with a three- to five-year time horizon for his investments. A team of 14 analysts, including four dedicated exclusively to the fund, help back his conviction.

With an active share of normally over 90% relative to the MSCI EAFE index, Hunt clearly takes a benchmark-agnostic, active approach to portfolio construction. He believes this makes his fund a good core international holding as well as “a strong complement to a passively managed or benchmark-focused international equity allocation.”

Although he focuses mainly on stock valuations and the corporate characteristics of his companies, he also keeps an eye trained on economic and market trends. It hasn’t escaped his notice that with the exception of a few flashes of glory, international markets have been underperforming the U.S. stock market for years. The upside, he says, is that stock market valuations abroad are much more compelling than they are in the U.S. And because foreign economies are in the earlier stages of recovery, the odds for profit upswings at foreign companies will be better once the recoveries finally take hold.

In some cases, external events have worked in favor of portfolio companies or created new buying opportunities. A weakening of the euro and yen, for example, makes export-oriented companies more competitive as revenue streams from the U.S. get a currency boost.

On the downside, a stronger dollar also means a decrease in share values for U.S. dollar-denominated international mutual funds. To mitigate the impact of currency translation, Hunt will sometimes deploy currency hedges. But the portfolio is mostly unhedged right now because he believes that the dollar isn’t likely to move much over the near term.

Hunt admits that he doesn’t see any particular catalyst that will turn the stock market tide away from the U.S. in favor of foreign countries. At best, he has hopes for “diminishing negative catalysts” as fears about China’s slower growth scenario and various political events in Europe subside. But he does have a definite opinion about which U.S. presidential candidate will be better for international markets.

“The fact that [Hillary] Clinton is well understood in the international arena reduces uncertainty,” he says. Donald Trump, on the other hand, “is rhetorically anti-trade and against many institutions that have brought the world together since WW II. Trade is good for the global economy. Period.”

Most of the companies in the fund are tied into world trade. One of them, French drugmaker and longtime holding Sanofi, has several strong, long-term franchises in areas such as vaccines and animal health, and is very active in emerging markets. But investors often shun the company in favor of competitors, such as Merck, that have fewer employees and lower production costs. Hunt believes that more investors will warm up to Sanofi when it eventually pares back its costs and improves efficiency.

Lower oil prices haven’t had much of an impact on the portfolio, which is light on commodity-related companies. But they have presented some buying opportunities as investors have punished companies with even a relatively modest exposure to oil prices. One of those companies is London-based Smiths Group PLC, a diversified multinational engineering company the fund first bought in early 2015. “Even though only 20% of the business was in oil and gas, investors were treating the company as if it had a 50% exposure,” Hunt says. “This was a good business trading cheaply because of a misunderstanding about the impact lower oil prices would have on the company.”

Applus Services, an inspection service for auto emissions and industrial plants based in Spain, is another oil price play that joined the portfolio last year. Even though its only relationship to energy prices is that it inspects oil and gas refinery and storage facilities, investors fled the stock when oil prices dropped. Hunt was attracted to the company’s consistent revenue stream generated by government-mandated inspections, and felt the downturn presented an opportunity to buy shares.

The case for Zodiac Aerospace began to emerge about a year ago, when the French maker of toilets for the aerospace industry became deluged with new orders that it was ill-equipped to handle. When production problems came to light, investors fled. “We saw a problem that was fixable,” Hunt says of his decision to buy the stock earlier this year. “Management was changing, and they were doing a better job of communicating with the public. They have the potential to fix their operations and get back on track. And if they don’t, an acquirer could come in and fix their problems for them.”

Recent fund purchases include Cobham plc, a U.K.-based niche manufacturer of electronics with strong positions in specialized military and communications markets. Cobham’s stock came under pressure as a result of a cyclical downturn among some of its customers, and a rights offering aimed at reducing corporate leverage enabled the fund to purchase shares of the company at a meaningful discount to intrinsic values. During the spring of 2016, the fund also took a position in drug and chemical company Bayer AG, when shares sold off in response to its bid for Monsanto. Hunt believes Bayer has a strong franchise in consumer and animal health, as well as crop science and pharmaceuticals, and that the value of these businesses combined exceeds the price of company shares. “Our assessment is that on a sum-of-the-parts basis, the stock should trade at 125 to 130 euros per share. When the stock fell below 90 euros, we jumped on it.”