My issue with Bullard is neither his assessment of the current macroeconomic regime nor the silliness of forward guidance and Fed communication policy. I am in violent agreement with Bullard in his recognition of the power of Narrative and the simple fact that all of our crystal balls are broken. But don’t tell me that the Fed “has no choice” but to accept the current macroeconomic regime, because they DO have a choice. The Fed giveth. The Fed can taketh away. It’s just a very, very, very painful choice that the Fed would have to make in order to taketh away, full of loss assignment and bankruptcy and status quo shattering. It’s a very brave choice they would have to make, a Volcker-esque choice they would have to make. And that’s why I don’t think they will ever do it.

So we’re left with Hope, hope that a miracle occurs after the November election to change our current political regime of decay and macroeconomic regime of low growth + massive debt + negative interest rates. Politically on the left, it’s hope that Hillary Clinton isn’t really as venal and principle-less and in-the-bag for Big Money and Big War as she seems. Politically on the right, it’s hope that Donald Trump doesn’t really mean what he says about Muslims and Hispanics and judges and torture and libel and debt and women and and and. On both the left and the right, it’s hope that the election will yield some massive Keynesian public infrastructure spending spree, where our “crumbling roads and bridges” are made whole, where every city gets a football stadium for the local billionaire’s use, and where high-speed rail and gleaming airports usher in a new age of productivity and easy trips to Grandma’s house. Truly, as Voltaire’s Pangloss would say, this is the best of all possible worlds.

But hope, of course, is not a strategy. What do investors and advisors and voters — The Non-Powers That Be — DO when the entire world is stuck in a powerful negative equilibrium, when we are presented with nothing but miserable choices, at the ballot box and public markets alike? How can we find “compensation in our disappointment”, to quote Thoreau? Or to be slightly more modern in our references, let’s accept that we can’t get what we want. Can we at least get what we need?

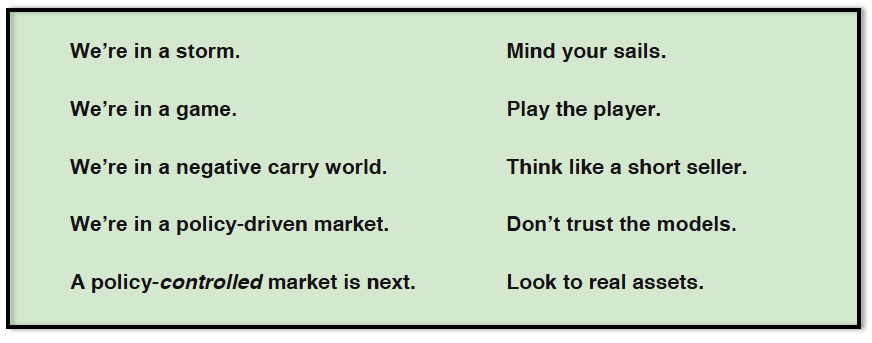

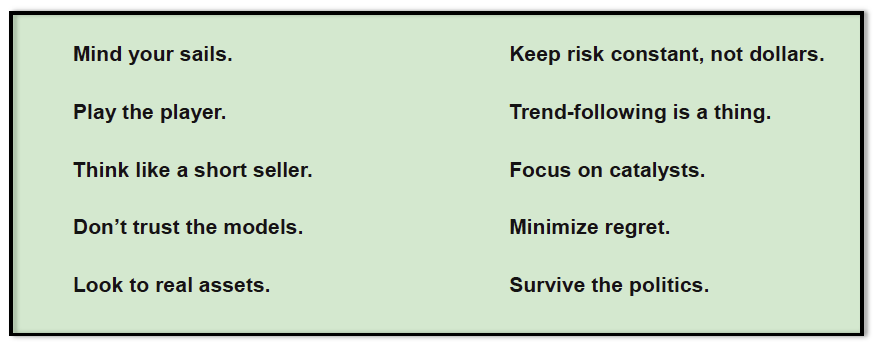

To answer that question, at least from an investment perspective, I need to go back to the big Epsilon Theory note I wrote earlier this year, “Hobson’s Choice.” I’m not going to repeat much of that here (at 26 pages long, it’s a bit of a tome), except to say that it’s as close to an Epsilon Theory investment strategy as I can convey in this public venue. But here’s the skinny, with what I call Five Easy Pieces for the Investment World As It Is.

In and of themselves, admonitions like “Mind your sails” may not sound like much, but I promise they make sense in context. Here’s what they mean translated into market behaviors.

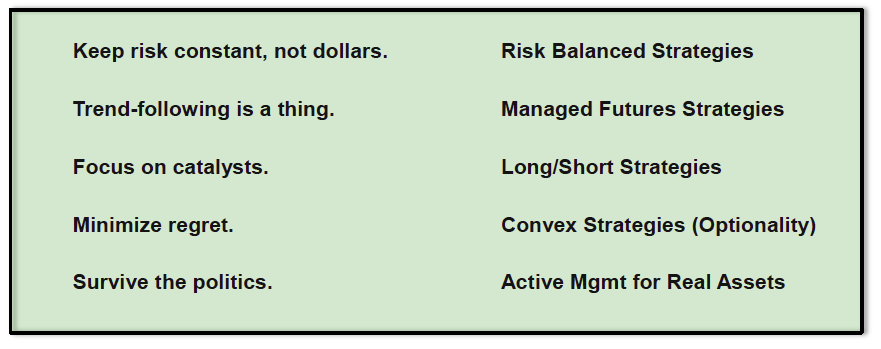

Now the point of “Hobson’s Choice” is that these behaviors I’m describing, like “Keep risk constant, not dollars”, are new ways of describing good old-fashioned investment ideas that just so happen to conflict with other investment ideas that have become rote articles of faith in our modern, overly equity-centric vision of what it means to be a “good” investor. For example, I think that it’s nuts to stay fully invested in the stock market through thick and thin, and I would love to embrace that most-hated epithet in investing today: market timer. (Shudder!) But I can’t SAY that I’m a market timer, any more than I could say that I’m a libertarian or that I love Emily Dickinson’s poetry or that my wife and I homeschool our children … no, no, you wouldn’t take me seriously if the conversation about politics or books or education were framed in this way. It’s the same with investing. In the immortal words of John Maynard Keynes, “it is better for reputation to fail conventionally than to succeed unconventionally” (and for an Epsilon Theory twist, I’d add, “and if you fail unconventionally, then your reputation is really dead”), which means that even if you agreed with me on the virtues of market timing, you’d never adopt a strategy based on market timing, because it would be way too risky from a social perspective. I mean, just imagine the shame if your client or wife or partner thought you were a … again, I can hardly bring myself to write the words … market timer. Oh, the humanity!

So let’s change the conversation. I’m NOT a market timer. Nope, not me. Instead, I’m a risk balancer. I have fewer dollars in the market when risk goes up, and I have more dollars in the market when risk goes down. Will I be over-invested in the market when it hits a top and rolls over? Yep. Will I be under-invested in the market when it hits bottom and turns up? Yep. But I’m going to be adding to my dollar exposure all the way up and I’m going to be subtracting from my dollar exposure all the way down. I’ll take those odds. And just imagine if I did this risk balancing thing across asset classes, or maybe across yield-oriented strategies. Hey, now.

Is this a comprehensive list? Of course not. But it’s a start. Over the next few months I’ll try to take each topic in turn and dig into the specifics, or at least as much of the specifics as I’m allowed in this very public setting. Some of the topics have already been discussed at some length in prior notes (for Convex Strategies, for example, be sure to read one of my personal Epsilon Theory faves, “I Know It Was You, Fredo”), others will be largely starting from scratch or going in a new direction from the past. If you’re a professional investor or allocator and want to dig in more deeply than what you read in these pages, don’t hesitate to reach out.

Ben Hunt, Ph.D., is the chief risk officer at Salient and the author of Epsilon Theory, a newsletter and website that examines markets through the lenses of game theory and history.

Here are the broad categories of strategies that the Five Easy Pieces market behaviors imply.

You know, Emily Dickinson published fewer than a dozen of her almost 1,800 (!) poems while she was alive, and if not for a determined sister with a narrow interpretation of Dickinson’s final wishes (she asked for her correspondence to be burned, and it was, but she didn’t specifically say anything about the box of poems next to her letters), all of this genius work would have been lost. In Dickinson’s day, there was way too much intermediation and way too many barriers between author and audience. We got lucky. Today, there’s way too little intermediation and way too few barriers between author and audience, such that all of us are inundated with “content” and “marketing collateral”, to use the lingo. Dickinson’s challenge was standing up. My challenge is standing out. Thanks to all of you who have actively spread the word about the Epsilon Theory project and helped build the vibrant community that we have today. Keep those cards and letters coming (I really try to respond to everything I get), and please check out the Epsilon Theory podcasts when you get a chance. It feels like we’re just getting started, and that’s something that warrants Hope, indeed.