The world’s central banks aren’t moving in harmony just yet, but at least the discord is beginning to fade.

The European Central Bank on Thursday ruled out further interest-rate cuts in a sign that it’s cautiously edging toward an exit from its stimulus program. Bank of England officials have been considering gradually removing accommodation in coming years, though a move is some way off and their assessment will have to take into account the fallout from the country’s messy election outcome. And while Japan’s central bank has no intention of removing stimulus soon, it is said to be re-calibrating communications to acknowledge that it is thinking about how to handle an eventual policy change.

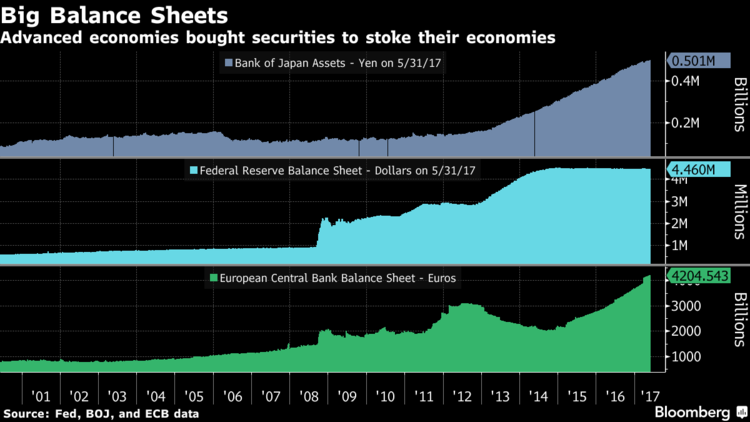

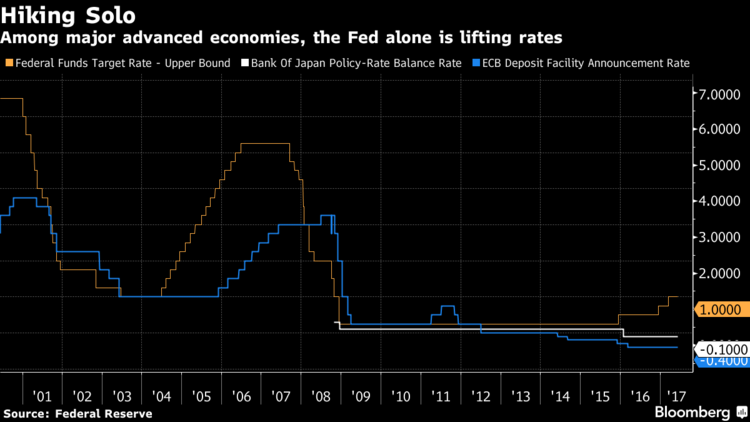

The Federal Reserve remains well ahead of the pack. The U.S. central bank is expected to lift rates for the fourth time this hiking cycle at its June 13-14 meeting and is mapping out a plan for unwinding its $4.5 trillion balance sheet, a process it’s handling gingerly to avoid roiling global markets. China, meantime, has been allowing money markets to tighten as policy makers seek to squeeze leverage from parts of the financial system.

The nascent signs of policy synchronicity in the world’s largest economies come as global growth improves. While central banks continue to undershoot their inflation targets, labor market slack is drying up in many places. World output is expected to expand 3.5 percent this year, according to International Monetary Fund forecasts, up from 3.1 percent in 2016.

‘Global Upswing’

“We’re in a sort of a global upswing,” said Jay Bryson, global economist at Wells Fargo Securities LLC in Charlotte, North Carolina. “Given that, you probably don’t need these super-accommodative policy stances anymore.”

The shift has been gradual and often subtle, yet it marks a sea change. Largely in unison, central banks employed unprecedented, unconventional easing to force their economies back into gear after the global financial crisis spurred widespread unemployment and a decade of sub-par growth. In many, that involved large-scale asset purchase programs. In the euro area and Japan, the response included negative interest rates.

The Fed has been reducing accommodation on its own since December 2015. Now, others are beginning to discuss unwinding their policies, restoring a sense of togetherness.

“We’re talking about a change from a situation where the central banks were basically pedal to the metal, full throttle, as much monetary stimulus as you could conceivably do,” said Jacob Funk Kirkegaard, a senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics in Washington. “Now, central banks in advanced economies are reacting to a recovering economy."

As hiring hums along and central banks tip-toe toward the exit, the Fed stands to benefit. The dollar has seen upward pressure as the U.S. central bank hikes and other monetary authorities ease, and a strong greenback means cheaper imports and lower inflation. The Fed’s preferred price index continues to undershoot its 2 percent goal.

“You don’t want it falling out of bed, but dollar depreciation would lead to higher inflation in the U.S.,” Bryson said. “Frankly, I think the Fed wouldn’t be that unhappy to see higher inflation.”

The change is also good news for the nations turning toward the exit, inasmuch as it signals that business confidence is picking up, more people are working, and the specter of another economic dip is fading from view.

In Japan, the economy has expanded for five straight quarters, the best run of growth in a decade, and unemployment has dropped to levels last seen more than 20 years ago.

While inflation remains stubbornly low, chaining the Bank of Japan to its stimulus program for the foreseeable future, some lawmakers have demanded the BOJ begin talking about how it may handle an eventual exit.

It’s taking notice. Officials realize it’s not constructive to remain silent on the issue and are making it known that the BOJ is conducting simulations internally on how an exit could play out, according to people with knowledge of discussions at the central bank.

Governor Haruhiko Kuroda and his board are expected to stand pat the conclusion of the next policy meeting June 15-16.

Draghi’s View

In the euro area, ECB President Mario Draghi took a tiny step toward an eventual exit from extraordinary stimulus by saying on Thursday that the risks to economic growth are now “broadly balanced” and another cut in interest rates is no longer on the table. Bond purchases are still intended to run until at least the end of the year, but economists predict them to be tapered in 2018.

In the U.K., the BOE said on May 11 that if growth keeps up as expected, “then monetary policy will need to be tightened by a somewhat greater extent over the forecast period than the very gently rising path implied by the market yield curve.”

That position assumed a “smooth” exit by Britain from the European Union, an outcome that may not be achieved if the Brexit negotiations become bogged down. The picture is even muddier now after Prime Minister Theresa May’s snap election held on Thursday led to a so-called hung parliament, where no single party has a majority.

Still, the broad thrust for advanced economies appears to be moving away from easing -- and they’re not alone. When the Fed hiked in March, the People’s Bank of China followed suit hours later, though economists are skeptical that it will repeat the move if the Fed lifts rates in June.

“This is all good news,” Kirkegaard said. “We should no longer be afraid of a double dip, a recurring global crisis.”

This article was provided by Bloomberg News.