A major source of volatility in the global financial markets over the past year relates to the emergence of a huge secular change in the global monetary order, the first since the early 1970s: China’s integration into the global financial system. Highlighting this change was the inclusion of China’s currency last November in the International Monetary Fund’s (IMF) foreign reserve asset known as the SDR (Special Drawing Rights), whose value is determined by a basket of international currencies, including the U.S. dollar, the euro, the yen and the British pound.

This integration is momentous, marking another major advance by China onto the world stage. China’s imprint on the global financial markets is now unmistakable; its actions influence foreign exchange rates, interest rates, capital flows, equity markets and, by extension, the decisions made by global central banks.

Adjustments to China’s integration contributed to the two swoons in global equity markets last August and this past January, with two dips of about 10% in major markets. The severity of these market moves demonstrates that investors need to gain a greater understanding of this “new order” to avoid the potential pitfalls and take advantage of the potential opportunities.

The sunny side of the disruption

China’s integration into the global economic system began literally decades ago, starting in 1978 with a series of market reforms in China. It accelerated after China became a member of the World Trade Organization in December 2001. Today, China is a dominant force in global trade and the world’s biggest exporter.

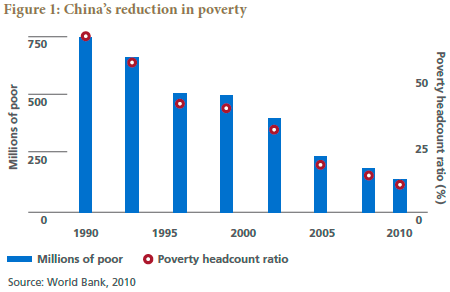

China’s rapid pace of economic growth, averaging around 10% for over 30 years, has been integral to its success on the world stage and is the fastest sustained expansion by a major economy in history.1 This growth has also led to remarkable domestic achievements, in particular a spectacular reduction in poverty2 (see Figure 1).

While this by far is the most notable achievement for the Chinese people, the increase in the standard of living is also evident in photographs taken of Shanghai recently versus 25 years earlier (see Figure 2).

In contrast to China’s relatively smooth integration into the global economy, China’s recent integration into the global financial system has been far less seamless, with investors focusing often on the negative near-term consequences.

There are legitimate causes for concern. For starters, China’s economic growth rate is slowing, probably toward 6% or so, its population is aging and it is attempting to transform an economy from investment-led to consumption-led on a scale never seen before. This requires a delicate balancing of many reforms that could easily tip China’s economic and financial system in the wrong direction. Moreover, China’s indebtedness has increased, and it is attempting to carefully manage a non-performing loan problem in the banking sector without upsetting its economy or its plan to transform its growth model.

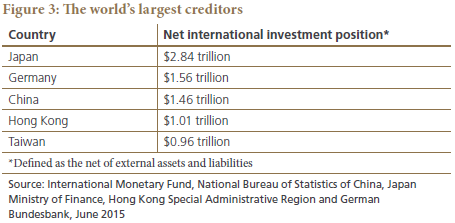

Despite these concerns, there are potentially positive considerations. China may someday surpass Japan as the world’s largest creditor (see Figure 3); it could thus provide an enormous amount of financial liquidity to the world, including neighboring Asian countries, which account for about a third of the world’s economic growth, well above the U.S., which accounts for about 22%, and Europe, at around 18%.

Those who today worry about capital outflow from China should perhaps consider the sunny side: Chiefly, the outflow frees up “trapped” capital in China that can then be invested in the rest of the world. Moreover, they may want to recall Bagehot’s dictum, which central banks have followed profoundly and effectively in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis:

“to avert panic, central banks should lend early and freely (i.e., without limit), to solvent firms, against good collateral…”

To this end, China’s role as a major liquidity provider could well increase in the new order if the yuan becomes more widely used as a form of payment and becomes a bigger share of the foreign currency reserves held by the world’s central banks. Today, however, very few reserve managers hold reserves in the yuan; most are held in U.S. dollars, as has been the case for decades.

China now tops the world in international reserve assets, with holdings of $3.2 trillion (out of $11 trillion held globally) built from the world gobbling up goods “Made in China” (see Figure 4). So China has both the wallet and the will to ably navigate these challenges – if it applies its skills to manage them. It bodes well that China has already achieved what many have dubbed an economic “miracle.” Perhaps investors should consider applying Warren Buffet’s “Don’t bet against America” mantra to China too until they find reasons to bet otherwise.

Uncertainty and plenty of it in the new order

Giving China the benefit of the doubt hasn’t been easy for investors given the volatility stemming from uncertainties over China’s foreign exchange policy. Investors ask, what exchange rate is China targeting? Which currencies will it manage against? At what speed would China like its exchange rate to move? Will China surprise investors yet again with more “one-off” currency devaluations?

China And The New Global Monetary Order

June 8, 2016

« Previous Article

| Next Article »

Login in order to post a comment