Risk management seems to be a household topic these days. No longer an exclusive province of quants, it is discussed regularly by the popular press. From the shortcomings of value-at-risk to the latest stress tests imposed by the Fed on banks, risk management has gone mainstream. But why has it failed so dramatically in 1998, 2000, 2007, 2008 and again in 2010 with the European debt crisis? We will argue that too much focus has been placed on backward-looking risk measures and not enough on scenario analysis.

Risk Management is not Clairvoyance and Market Timing

But what is risk management anyway? While almost everyone uses the words ‘risk management’, the implied meaning seems to differ from person to person. Let’s start by discussing what risk management is not. Risk management is not about being a clairvoyant. It is not about forecasting specific future events. It is certainly not about timing those events i.e. ‘the big short’. Risk management is all about finding the suitable risk/return profile. Suitable, that is, to the holder of the portfolio. When your client has a suitable portfolio, he or she will not sell when the losses hit, because the possibility of those losses was discussed right from the beginning. The biggest problem for most investors is that they get in near the top and get out near the bottom. ‘Suitability’ ensures that this vicious circle is disrupted. If your clients don’t get out at the bottom, then they won’t have to jump back in at the top. But the only way that could happen if their risk/return tradeoff was chosen by considering a variety of scenarios: good, bad and ugly. Showing low risk simply because the realized volatility is low and VIX is heading toward single digits cannot really be called risk management. That is called rear view mirror driving.

Why Stress Testing?

Why do we need stress testing when we already have risk measures like Sharpe ratio, Beta, Value-at-Risk, Tracking Error, and Expected Shortfall? The problem with these measures is that they are completely backward-looking. A tracking error or a Sharpe ratio today has no clue that interest rates can actually rise by more than trivial amounts, since nothing of that kind was observed in the data sample used to calculate those metrics.

Moreover, if you ask one of these measures about the possibility of a simultaneous rise in interest rates and a drop in equities, it will likely tell you that the probability of such a one-two punch is zero. When those measures will gain that knowledge, it will be too late to be useful, since the events will have already happened. Backward-looking risk measures still view long-dated Treasuries and any instruments with a great deal of interest rate risk as virtually riskless, due to the low volatility and safe haven appeal that we have observed over the recent decades. This will lead you to underestimate probabilities of events that are quite plausible in the next few years, such as inflation or stagflation.

Stress Testing Gaining Prominence

Have you noticed how Fed stopped talking about Value-at-Risk for banks? It practically disappeared from popular discourse starting in 2009. The Fed and the ECB now routinely talk about stress testing of banks. Of course, stress testing can also be misused and gamed by the banks, but at least they realized that estimating risk simply based on what happened over the past couple of years is a rather flawed strategy.

Shortcomings of Stress Testing

Every tool has limitations and has to be used properly. A Maserati is not a bad SUV, it simply isn’t meant to go off-roading. Similarly, most of the arguments against stress testing are really arguments against a misplaced utilization of that tool, not against the tool itself.

But didn’t Nassim Taleb teach us that crises are ‘Black Swans’, events that cannot be modeled or anticipated by definition? That there are an infinite number of possible crises out there and our finite minds cannot possible make sense of all of them and prepare. Of course, if you subscribe to this theory then the only logical action you can take to be successful is to buy lottery tickets and wait until your ship comes in. Dr. Taleb calls it exposing yourself to positive right tail events. Or you can become a best-selling author, but the chances there are sadly even smaller than winning a lottery. In reality, financial crises are quite similar. They can easily be categorized into crash impacts, just like car crash impacts such as frontal, rear, side, rollover etc. There are certain types of fundamental building blocks of the financial system that can be used for this purpose: equity prices, interest rates, spreads, commodity prices, other real assets etc. Take those and break them up by region and you can have a list of possible events that will cover just about everything, except natural disasters (which along with sudden geopolitical hostilities are the true black swans). The Lehman Collapse of 2008 and the LTCM crises of 1998 had great many similarities in the mechanism of the market dislocation. Southern Europe sovereign debt problems of 2010 are not dissimilar from the past sovereign debt problems regularly observed in the financial history (check out This Time is Different by Reinhart and Rogoff).

Once the list of plausible events is identified, you do not want to be overly focusing on any single one to the exclusion of others. You certainly do not want to be timing them, as nobody can do that consistently.

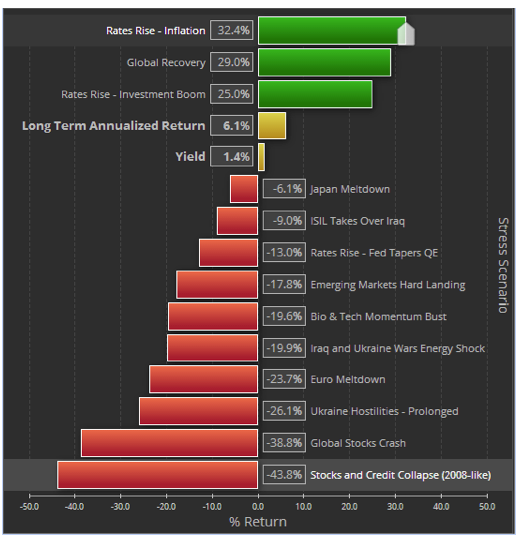

Sample Stress Test

Here is a picture of a sample stress test. Though your stress test summary can look different, the key is that it should include a variety of plausible events that can be explained to the client in plain English. Remember, our main goal is to create a suitable portfolio. To do that we need to get buy-in to reduce the chances of the client selling at the bottom and (as a consequence) getting back in at the top. The stress test report should also include events with some upside as well as some indication of the long term performance and current yield of the portfolio.

Exhibit 1 – Sample Crash Test

Risk Adjustments

At this point a reasonable question might be asked. What if we clearly see that valuations are stretched, leverage is off the charts, complacency at all-time highs? Should we not react to that just because we cannot time the crash? The answer is that we should absolutely monitor such systemic risk trends. But we should be humble and remember that timing is quite difficult. Instead we can either de-risk or buy portfolio insurance.

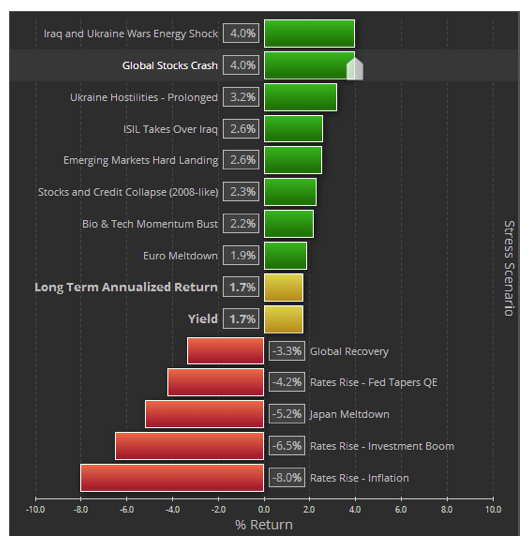

De-Risking

Most of the time de-risking is taken to mean shifting of the allocations to include more fixed income. Here is an extreme example of that where a whole portfolio is placed into the PIMCO Total Return fund. I am not the first one to point out that the expected yield on such investments is paltry, the upside is very limited to say the least and there is a real risk of losses if (when) rates rise.

Portfolio Insurance

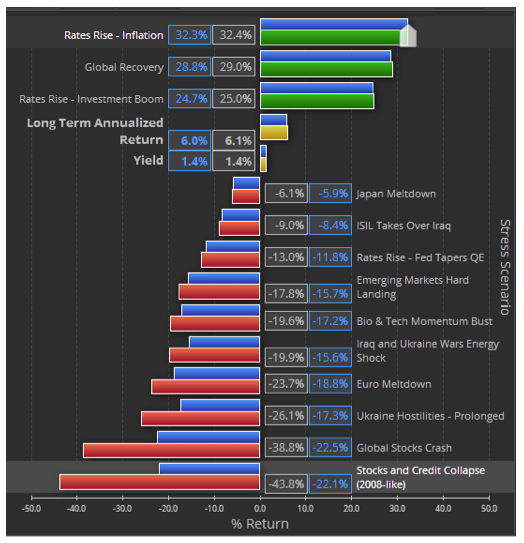

So, fixed income does not sound very appealing as a de-risking strategy. Low yields and not such a low risk do not seem like a great combination. But there is an alternative. When we see irrational exuberance and madness of crowds, it might make sense to consider put options. They give protection without the necessity to time the market. The nice benefit is that during times of exuberance, the prices of options are fairly moderate. Exhibit 2 shows the same Moderately Aggressive portfolio after we have optimized it to limit the loss in a 2008 repeat to 22% instead of ~42% that the portfolio was losing originally. The best practice is to use deep out of the money options to keep the costs low. We are not trying to get rid of all losses, but simply cushioning the blow to the degree that the client can stay with the aggressive portfolio and does not bail out at the bottom.

Exhibit 2 – Original Portfolio (green/red bars) and Optimized (blue bars) with insurance

We see that we have kept the upside and limited the downside. In order to get this result we have paid an insurance premium. In our case, we used the put option on SPX with the strike price of 1450 and expiration in December 2014. The option costs $2.50 per contract and in the case of a repeat of 2008 (a ~45% drop in SPX) it will be worth $374. Thus, for a $1M portfolio it is estimated to give a benefit of $220K while spending only about .15% (600 options at $2.50 each) of the portfolio value on the premium. Of course, there are caveats and assumptions to running an options strategy, from the available volume to bid/ask spreads and rolling of the options after they expire in December. In addition, options should be traded by a professional familiar with volatility surfaces. However, even increasing the potential costs up to 1% annually can still give an economical way to limit the downside, while keeping the upside for growth in appropriate situations. Fixed income just can’t give you that.

Daniel Satchkov, CFA, is the president of RiXtrema Inc., a risk modeling and consulting firm that focuses on the extreme financial market events.