Source: GaveKal Capital

Finally, for the dividend growth rate we assume a 6 percent annual growth rate. We base this assumption on a mean reversion for the corporate payout ratio (dividends/earnings) over the next several decades back to its long-term average. As charts 2 and 3 show, the payout ratio in the United States is at a very low level relative to where it has been for the last 142 years. This could be due to corporations’ focus on using cash flow to buy back stock rather than distributing it to shareholders. This is ultimately detrimental to long-term equity investors because share buybacks are a return of capital not a return on capital. Without the return on capital, investors are unable to accumulate more shares and take advantage of the power of compounding. We assume that this will correct over the long-term and a 6% dividend growth rate would gently move the market back to a historically normal payout ratio of around 60% over the next three decades.

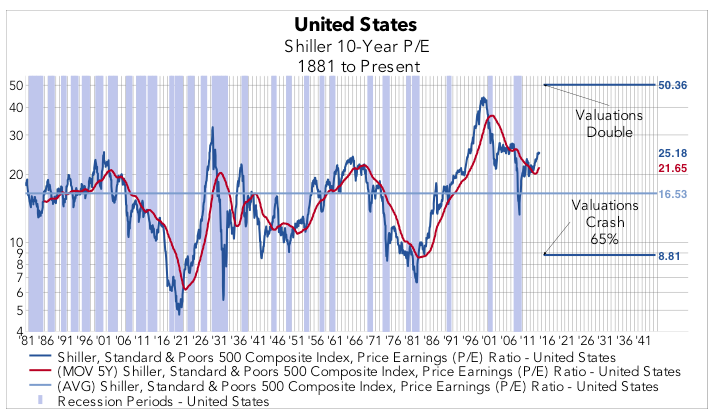

In our example, we assume we are living in a binary world where one year from now we either have a doubling in valuations or valuations fall by 65 percent. We also assume that the new valuation levels prevail for the next 30 years. In chart 4, we illustrate these two valuation changes within the historical context of the past 142 years.

Source: GaveKal Capital

Source: GaveKal Capital If you could choose what happens in the stock market tomorrow, would you prefer it to double or drop by two-thirds? For long-term investors, the choice may not be as obvious as it seems.

If you could choose what happens in the stock market tomorrow, would you prefer it to double or drop by two-thirds? For long-term investors, the choice may not be as obvious as it seems.

During a cyclical bull market like the one we have been in for the last five and half years, with stock markets making glorious all-time highs and valuations marching steadily higher, it’s easy to forget one of the most basic rules of investing: compounding of dividends trumps price appreciation over the long-term.

This may seem counterintuitive at first blush. Who wouldn’t prefer a doubling of the S&P 500 versus a two-thirds decline? In fact, for long-term investors and under certain conditions, a crash would produce a larger annual return over a 30-year horizon. In the charts and discussion below, we explain how that works.

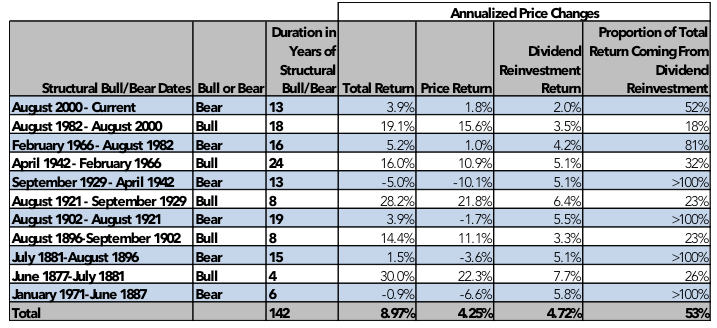

Total return for investors is made up of two pieces: price appreciation and dividend reinvestment. While price appreciation always makes the headlines, it is dividend reinvestment where the long-term investor in fact makes the money. To test this rule, we examine the total return of the US stock market going back to 1871 (chart 1).

We break out the data in different time periods based on whether the market was in a structural bull market (i.e. valuations expanding) or in a structural bear market (i.e. valuations compressing) and show returns on an annualized basis. In the far right column we calculate the proportion of total return that comes from dividend reinvestment. We find that dividend reinvestment accounts for the majority of total return over the entire 142 years and the vast majority of total return in a structural bear market. On an annualized basis since 1871, the stock market has had an 8.97 percent total return, of which, dividend reinvestment has accounted for 4.72 percent or approximately 53 percent of the annualized total return. When we are in a structural bear market, as we have been in since August 2000, the proportion of total return coming from dividend reinvestment rises to an eye-popping 89 percent. Without dividend reinvestment, an investor’s average annualized return would actually be negative during structural bear markets. In addition, in four of the six structural bear market periods -- lasting for a total of 53 years -- dividend reinvestment has accounted for over 100 percent of an investor’s total return.

The reason dividends are so crucial to long-term investing is the simple fact that dividends allow your money to work for you. Reinvested dividend distributions allow one to acquire more shares and those additional shares increase one’s future dividend distribution. This enables one to acquire more shares, which increases the future dividend distribution and so on and so on. The exponential power of compounding is the key to wealth accumulation, and dividends unlock this power for stock investors.

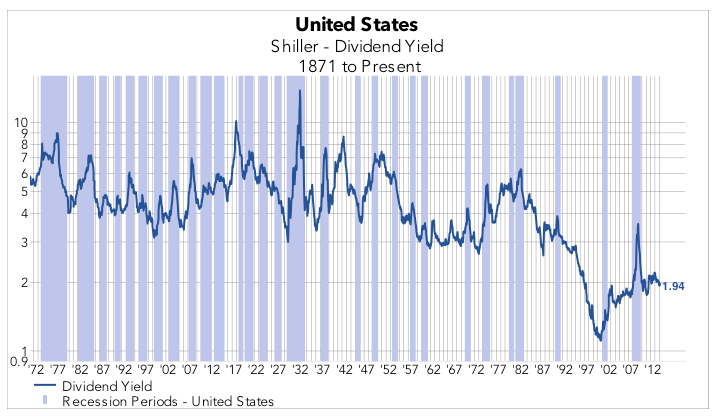

Let’s study this power with a simulation. As with all simulations, the inputs are critical to the formation of conclusions. Thus, we do our best to place our assumptions in a historical context. We have three main assumptions in this example: EPS growth rate, dividend yield, and dividend growth rate. For the EPS growth rate we use a 4 percent growth rate that is in line with long-term nominal GDP growth expectations. For the dividend yield we use a 2% yield since this is approximately the dividend yield for the S&P 500 currently. The average dividend yield for the US stock market over the past 142 years is closer to 4.5 percent.

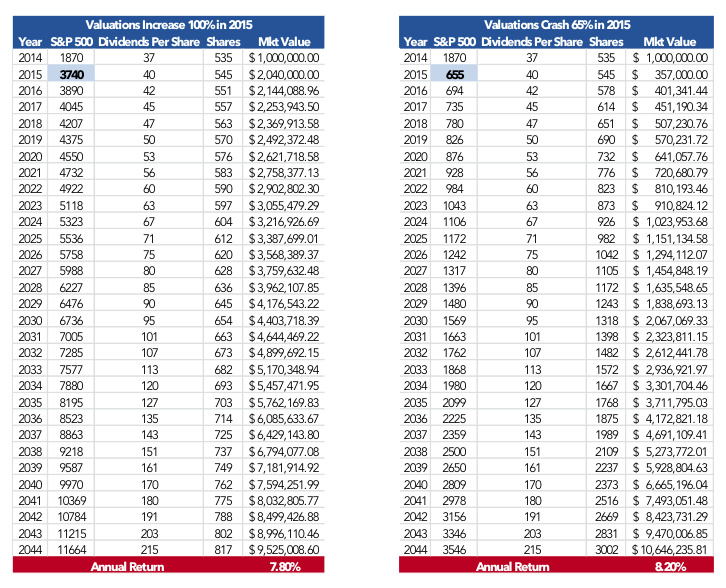

First, let’s take a look at the total return for an investor if he or she is fully invested. On the left, we have modeled the one-time doubling of valuations in 2015 in light blue. On the right, we have modeled the one-time crash in valuations by 65 percent in 2015, also in the light blue. In each situation, the beginning market value of the portfolio is $1,000,000.

The annualized total rate of return over 30-years is actually 40 basis points higher when valuations dramatically decline. The reason for this can be found in the shares column. The number of shares owned at the end of the simulation period when valuations double is 817 compared to 3,002 shares when valuations crash. The quantity of shares that can be purchased when dividends are reinvested is much larger after valuations have dropped. This allows investors to accumulate more shares, which increases their compounding capacity, and leads to greater wealth accumulation over the long-term. A doubling in price actually has the opposite effect. The quantity of shares that can be purchased is much lower so the power of compounding is reduced. Higher prices don’t compound but the reinvestment of dividends does.

Crashes, Cash And The Art Of Long-Term Investing

June 4, 2014

« Previous Article

| Next Article »

Login in order to post a comment