Cash also plays an important tactical function. Not being fully invested today provides the option to invest tomorrow at a significant probability of lower (or higher) prices. This tactical use of cash will remain an important tool in the investor’s kit. Such an option value is a far cry, however, from the theoretical construct of a positive real rate of interest compounded over many years as the foundation of the return on our investment portfolios. For today’s investor, cash and government bonds should become less of a core investment and more a speculative source of potential timing alpha.

Higher-Yielding Real Assets

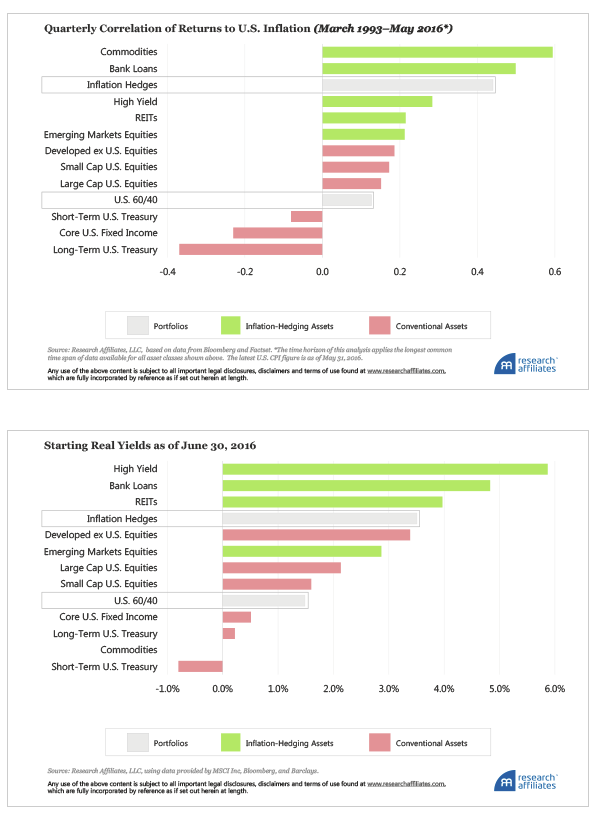

Asset classes that have historically provided a positive correlation of returns to inflation include commodities, bank loans, high-yield bonds, REITs, and emerging market equities. With today’s fear of deflation, many of these inflation hedges are on sale. An equal-weighted portfolio of the five inflation-hedging asset classes provides higher real yields than a traditional portfolio of domestic equities and core bonds.

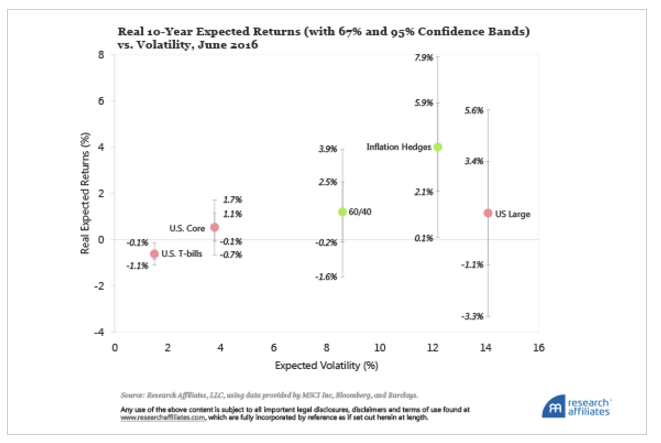

Higher starting yields predict higher subsequent long-term returns. Using the expected return methodology documented at researchaffiliates.com/assetallocation, we estimate a 10-year annualized real expected return of −0.6% for T-bills, 0.5% for core bonds, 1.2% for a traditional domestic portfolio of 60% stocks and 40% investment-grade bonds, and 4.0% for an equal-weighted portfolio of the five previously mentioned inflation-hedging asset classes. To be sure, with higher expected returns comes higher forecast volatility of annual returns, from 1.5% for T-bills to 3.8% for core bonds, 8.6% for the traditional 60/40 portfolio, and 12.2% for the inflation-hedging portfolio.

Does the higher volatility associated with the higher expected return increase risk for a long-term investor? When we compare the expected range of real wealth at the end of 10 years, we find much of the higher dispersion of expected real return for the inflation-hedging portfolio is on the upside. Our 95% confidence band for annualized 10-year real returns is −1.1% to −0.1% for T-bills, −0.7% to 1.7% for core bonds, −1.6% to 3.9% for a traditional 60/40 portfolio, and 0.1% to 7.9% for our inflation-hedging portfolio. For a long-term investor, the near certainty of exceeding the long-term real return on T-bills, with only the magnitude in question, doesn’t seem like much of a risk.

Conclusion

The persistence of negative real interest rates across developed cash and government bond markets contradicts our conventional understanding of a risk-free rate. We must therefore abandon our assumption that a positive real risk-free rate of interest undergirds the long-term returns of our investment portfolios. Central banks have engineered these negative rates through large scale purchases of securities from the market and the corresponding creation of bank reserves. If and when they take the next step of direct money creation, as is increasingly being discussed, long-run risk of inflation will rise. Investors should consider repositioning their portfolios now to avoid the zero to negative returns of cash and government bonds and to protect against long-term inflation. Investors should diversify away from government bonds and U.S. equities into higher-yielding inflation-sensitive asset classes such as commodities, bank loans, high-yield bonds, REITs, and emerging market equities.

Chris Brightman is chief investment officer at Research Affiliates.

Death Of The Risk-Free Rate

July 15, 2016

« Previous Article

| Next Article »

Login in order to post a comment