Last week we looked at the world’s demographic destiny for the coming decades. I imagine most readers perused the information and said, “Yes, we already know the world’s population is getting older. Everybody keeps saying demographics are important, but I’d like to know how slowly changing demographics actually affect the economy here and now.

Today we are going to explore how demographic change impacts growth. (We will use lots of charts and graphs, but the text of the letter is actually shorter than usual. The whole picture is worth 1000 words thing.)

Delta Force

Every politician and economist wants to see the United States – and, I should point out, Europe, Japan, and the rest of the world – return to 3%-plus growth. Given that GDP in the first quarter turned out to be just 0.6% and that growth has sputtered along at less than 1% for the last six months, even the 2% growth that we’ve been averaging for the last five years sounds good now. In my just-concluded series, a letter to the next president on the economic situation he or she will face, I laid out my own plan to reinvigorate growth. But I have to admit that plan does face a strong headwind called fundamental economic reality.

Growth in GDP has only two basic components: growth in productivity and growth in the size of the workforce.

That’s it: there are two and only two ways you can grow an economy. You can either increase the (working-age) population or increase productivity. There is no magic fairy dust you can sprinkle on an economy to make it grow. To increase GDP you have to actually produce more. That's why it's called gross domestic product.

The Greek letter delta (Δ) is the symbol for change. So the change in GDP is written as

ΔGDP = ΔPopulation + ΔProductivity

That is, the change in GDP is equal to the change in the working-age population plus the change in productivity. Therefore – and I'm oversimplifying quite a lot here – a recession is basically a decrease in production (as, normally, population doesn't decrease).

Two clear implications emerge: The first is that if you want the economy to grow, there must be an economic environment that is friendly to increasing productivity.

I really want to focus on demographics and the effects that change in the working-age population will have on the growth of the economy, but let me quickly offer a few rather disconcerting graphs on the continuing decline in productivity in the US. I should note that this situation is mirrored across the developed world.

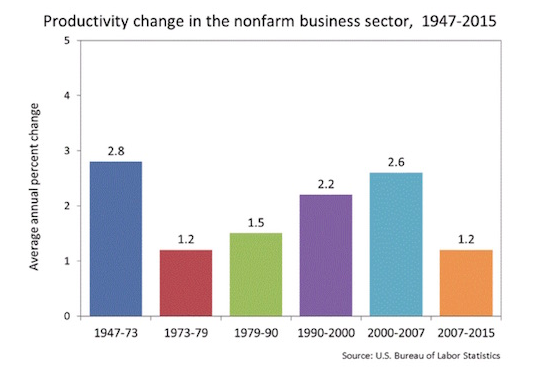

Productivity grew 0.6 percent in 2015, the smallest increase since 2013. Productivity increased at an annual rate of less than 1.0 percent in each of the last five years. The average annual rate of productivity growth from 2007 to 2015 was 1.2 percent, well below the long-term rate of 2.1 percent from 1947 to 2015.

Economists blame this decade’s reduced productivity on a lack of investment, which they say has led to an unprecedented decline in capital intensity. That is why those same economists want to keep interest rates low so that, in theory, businesses will be inclined to invest. However, there are those of us who believe that the artificially low rates put in place by central bank monetary policy actually cause reduced investment, and here’s why. Rather than encouraging businesses to compete by investing in productive assets and trying to take market share, excessive central bank stimulus encourages businesses to buy their competition and consolidate – which typically results in a reduction in the labor force. When the Federal Reserve makes it cheaper to buy your competition than to compete and cheaper to buy back your shares than to invest in new productivity, is it any wonder that productivity drops?

Look again at the chart above. Notice that in the high-inflation years of the ’70s productivity fell to roughly the level where it is today. In this next chart we see that actual productivity has grown less than 0.6% in the last two years. Toward the end of the letter we’ll come back and apply these productivity numbers to our equation above. As you might expect, this exercise will not make for pleasant reading.

The numbers suggest that productivity growth has become hard to achieve in the developed world. Mustering growth is harder in emerging markets, too, due simply to their own success. China moved millions of people from hardscrabble farming to factory floors in a relatively short period. Of course their productivity rose. So did productivity back on the farms, thanks to new machinery. Those easy gains having been booked – further productivity growth will be more elusive.