To many people, investing in commodities is about capitalizing on short-term price swings. To MacKenzie Davis, one of the managers of the RS Global Natural Resources Fund, it's about getting down and dirty to find stocks worth holding on to for the long haul.

The 39-year-old manager pokes around mines, wells and fields in both the U.S. and Canada, as well as in more far-flung locales such as Vietnam or even the Arctic Circle, to get a complete view of companies and their natural resources. On a recent whirlwind tour of Australia, Davis and portfolio manager Ken Settles visited with 16 companies, scrambled around two iron ore mines, and toured a port facility, all in just a few days.

"The only way to really know about a company's natural resource assets is to put a hard hat on and take a look at them," says Davis. "What it comes down to is geology that was put in place millions of years ago and good management that knows how to allocate capital."

The goal of these investigations is to find companies with low production costs and attractive geological assets that allow them to make money even if commodity prices stagnate or drop. It's a timely strategy at a time of slow economic growth, when commodity prices are likely to be constrained and it's essential to keep down costs.

That wasn't the case for much of the last decade, when the growth stories in emerging markets such as China, Brazil and India pushed commodity prices higher. The prices collapsed, however, during the 2008 financial crisis, and between May and November of that year the S&P Global Natural Resources Index fell 58%. Although commodities have gained ground since then, a slower growth environment, even among burgeoning emerging market economies, has kept prices in check.

Davis cites a number of reasons for investors to maintain some exposure to natural resources. Even with the worldwide economic slowdown, emerging market countries are still seeing high-single-digit GDP growth rates. These countries' commodity needs will expand in the coming years, so they will continue to help drive demand for natural resources. Furthermore, commodity prices have held up surprisingly well in the face of sluggish economic growth in most countries.

Davis says the most convincing long-term arguments lie on the supply side of the equation, since natural resources are finite. The reserves have been well-tapped, and companies have not invested heavily in locating and developing new ones as prices sag. Until those prices rise, there is little financial incentive to spend more to increase production. The government takeover of oil, copper and other resource reserves in some countries adds another set of supply constraints, since governments almost always run them less efficiently than private enterprises.

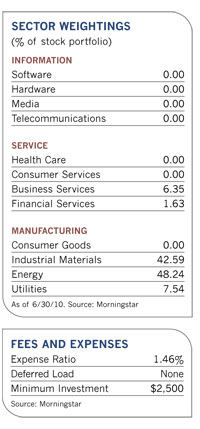

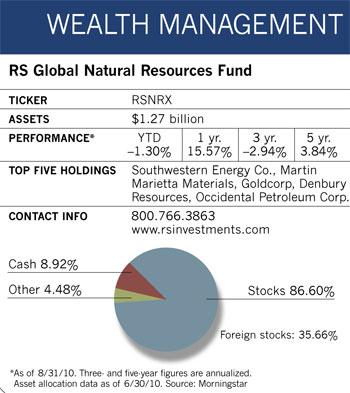

To minimize that threat, the fund avoids companies in countries such as Russia and parts of Latin America where commodities could likely be repatriated. Otherwise, the fund spreads a wide geographic net by buying names headquartered in the U.S., Canada, Chile, Australia and any other place where regulations require reporting transparency from public companies. At 44% of the assets, energy stocks play an important role in the fund's assets, though RS Global Natural Resources holds a variety of large stakes in other sectors as well, such as copper, coal, diamonds and precious metals.

The managers focus on industries where there are notable differences between the companies' costs of production and their geological assets. These differences produce a "steep cost curve" in industries such as oil, gold, copper and coal that can have a huge impact on profitability.

"Let's say you have a gold mine that's essentially a big open pit with easy access to high-grade gold," Davis explains. "That project is going to require a limited amount of capital to extract gold from the ground. At the other end of the spectrum, you've got a project with a mine that's a mile under the surface and a lower grade of gold. That capital-intensive producer is going to require much higher gold prices to be profitable."

The same pattern holds true in the oil industry. "A lot of oil companies require prices of at least $70 a barrel to break even," says Settles. "The low-cost producers we own only require $40 a barrel pricing to do that."

The cost structures are different for those companies in steel, aluminum and zinc production. Their flatter cost curves make clear winners harder to see, so the fund's managers usually don't find these stocks attractive.

Davis points to fund holding Goldcorp, which owns large mines in Mexico, Chile and Canada, as an advantaged producer with an efficient cost structure, good management and attractive assets. "Goldcorp would be cash-flow positive even in an environment of $400 an ounce gold, and it can easily do well in a $600-an-ounce environment," he says. He adds that the stock has appreciated at an annualized rate of nearly 30% over the last decade, outstripping 14% for the price of gold.

Another longtime fund holding is natural gas producer Southwestern Energy, which owns highly productive drilling sites such as the Fayetteville Shale in Arkansas, where it acquired drilling leases in 2002 after the discovery of gas-bearing deposits. "This is almost a paragon of the kind of company we're looking for," says Davis. "Southwestern is sitting on a large inventory of wells, and its low production costs will allow it to generate an attractive rate of return even if gas prices remain low."

Certain commodities, such as crushed rock and salt, don't trade on futures exchanges, so they tend to be less sensitive to the economy than those that do. Stocks tied to these commodities thus offer an important element of diversification, and RS Global Natural Resources has about one-third of its assets in them.

For example, Canadian salt miner Compass Minerals International sees its business heat up when the weather is cold and demand for road salt increases. "Salt prices have risen 3% to 4% annually over the last few years, so this is a great hedge against inflation," observes Settles. "Compass owns the largest salt mine in the world. And because the salt body is unusually thick, the company has a huge mining cost advantage."

The salt mine's location near Lake Huron means Compass can transport the mineral on barges or ships, which cost less than the trucks that the company's inland competitors rely on. With commodities that are relatively plentiful, such as salt or iron ore, low-cost transportation can give a company a major edge over its competitors.

Because commodity sectors only accommodate narrow groups of advantaged producers, the fund's holdings are smaller-with only about 30 securities, about half the number populating the typical natural resource fund. Settles says too much diversification can cramp performance in this space.

"Owning a large number of commodity stocks really doesn't provide any real protection against risk because you are going to have more high-cost producers in the mix," he argues. "Across a long-term commodity cycle, those types of companies are going to destroy value." But if the number of firms is smaller, so is the turnover ratio of 34%-which is about one-third that of the fund's competitors in the natural resource space. It attests to the long investment time horizon for the kinds of companies the managers like.

Settles points out that over the long term, the stocks of low-cost producers have generated returns well in excess of their underlying commodities. "Over the last decade, annualized returns from most commodities have ranged from zero to 5%, and commodity ETF prices have pretty much followed that pattern," he says. "Over the same period, low-cost producers have generated annualized returns in the 15% to 25% range. So what you're getting with these stocks is the intrinsic value of these companies along with commodity exposure."

The fund may lag commodities over shorter time periods when natural resource prices are escalating rapidly. But Davis says the fund makes up for that in volatile or declining markets and, more important, over the commodity price cycle, when the fund's focus on managing risks can yield better returns. The fund beat the S&P GSCI Total Return Index, a diversified index of commodities, over the ten years ended December 31, 2009 by logging annualized returns of 16%, while the index returned 5%.

Another drawback, however, is that commodity companies can suffer as many big short-term fluctuations as the items they dig up. In the ten years ending December 31, 2009, the fund's annualized standard deviation was 23.71, just a tad lower than the 25.20 annualized standard deviation of the S&P GSCI Total Return Index.

Morningstar analyst Jonathan Rahbar notes that while the fund's trailing ten-year returns are well ahead of the competition and trounce the S&P Natural Resource Index's gain, its volatility "is still meaningful, so added caution is warranted when investing in any option focused on natural resources."

Furthermore, the correlation between commodities and U.S. large-cap stocks has been higher than historical averages in recent years. But Davis believes the fund is still a good diversifier and an insurance policy against inflation.

"It's also a way to participate in the growth dynamics of emerging markets without emerging market risk," he says.