In the fourth quarter of the Oct. 29 football game between No. 3 Clemson and 12th-ranked Florida State, the Seminoles were thinking upset. FSU led 28-26 when star tailback Dalvin Cook ripped off a 50-yard run into Clemson territory.

Then came a penalty flag for an illegal block, negating the play. FSU Coach Jimbo Fisher stormed the sideline, screaming at the officials, dropping an apparent F-bomb. Then came another flag, for unsportsmanlike conduct. FSU punted. Clemson escaped with a 37-34 win.

Fisher resumed his tantrum at a postgame press conference, blasting the game’s officials as “gutless” and “wrong.” Eyes bulging, Fisher said, “You hold coaches accountable [and] players accountable—hold the damn officials accountable.” The Atlantic Coast Conference, which includes both FSU and Clemson, later fined Fisher $20,000.

Blaming the zebras is hardly novel. But Fisher’s tirade revived a question that has taken on greater significance in the era of lucrative college football playoffs: Do officials paid by the top NCAA conferences slant their calls—even if only unconsciously—to help their employers’ top teams? New research suggests the answer is yes.

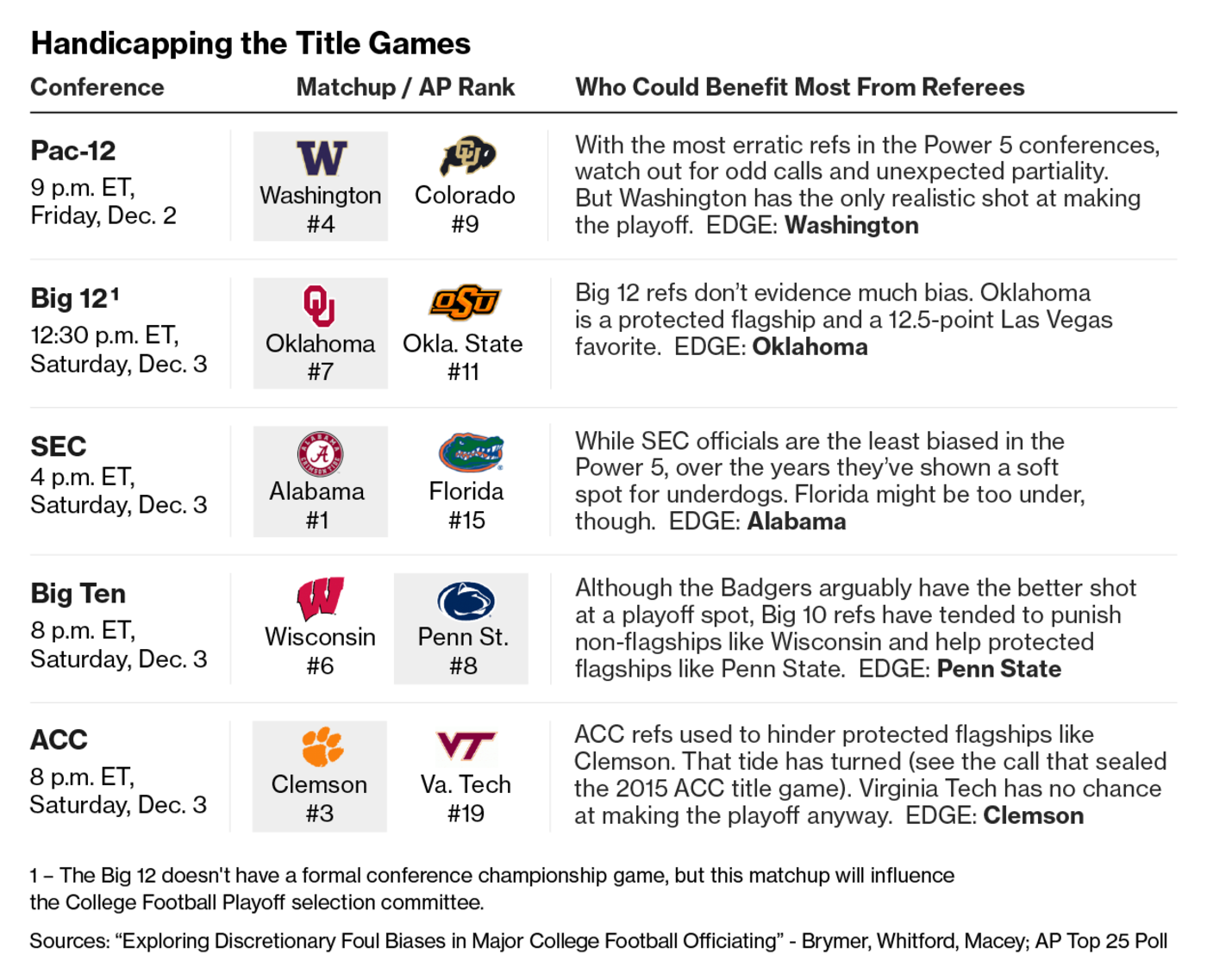

Unlike in NCAA basketball, which draws referees from pools overseen by groups of conferences, most football referees are hired, trained, rewarded, and disciplined by individual conferences. That means officials are entrusted with making decisions that could hurt their employers—as with the call in the Clemson-FSU game. Clemson was the ACC team with the better shot at making the College Football Playoff and the financial bonanza it dangles.

“This is an incestuous situation,” says Rhett Brymer, a business management professor at Miami University in Oxford, Ohio. He spent more than a year parsing almost 39,000 fouls called in games involving NCAA Football Bowl Subdivision teams in the 2012-2015 seasons. His research finds “ample evidence of biases among conference officials,” including “conference officials showing partiality towards teams with the highest potential to generate revenue for their conference.”

It’s potentially a big deal now that the playoff has become such a rich source of cash for the Power 5 conferences that supply the teams: the Big Ten, Pac-12, Big 12, Southeastern Conference, and ACC. Those conferences split about $275 million in bowl-season television money, and get paid an additional $6 million for each of their teams that qualify for the four-team playoff, plus $2.16 million for expenses. That’s on top of money for game tickets and merchandise, as well as the recruiting bump that can help schools return to the playoff year after year (see Alabama).

The Miami of Ohio research offers no evidence that specific officials intentionally skewed game outcomes. Nor does it assert that conferences would try to manipulate the part-time, independent contractors who officiate for $2,000 to $2,500 a game.

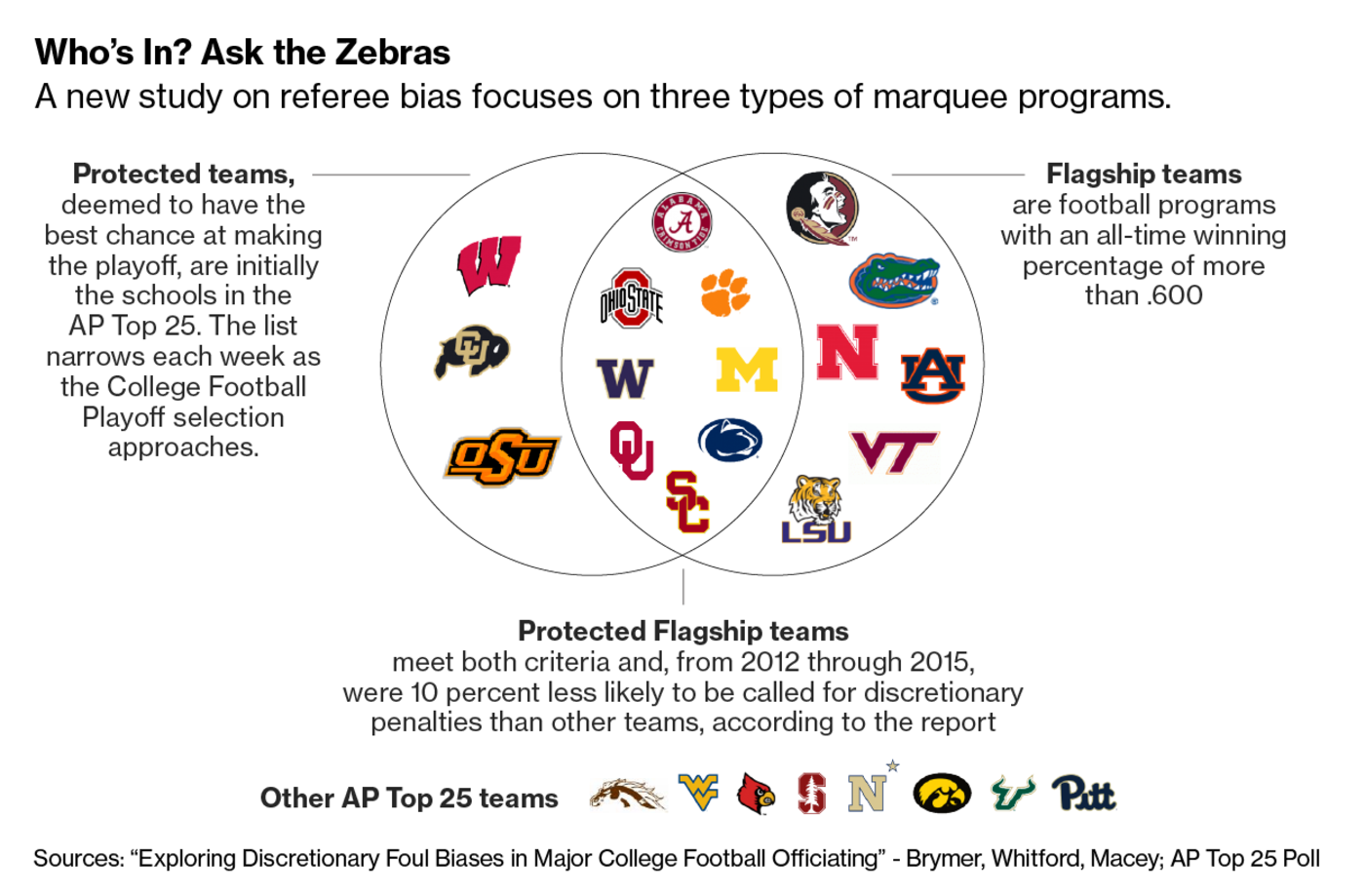

Brymer’s data suggest something more insidious. Across the 3,000-odd regular-season and bowl games he studied, a bit less than half of the fouls called were what he terms “discretionary”—holding, pass interference, unsportsmanlike conduct, and personal fouls like roughing the passer. Refs were on average 10 percent less likely to throw discretionary flags on teams that enjoy both strong playoff prospects and winning traditions. Brymer calls these teams “protected flagships.”

Protected flagships in the Big Ten did especially well with officials, the research shows. Ohio State, the conference’s most competitive flagship team in the years Brymer studied, was 14 percent less likely to be dinged for a discretionary foul than, say, Purdue, a non-flagship team with little chance of contending for a national title. The Buckeyes fared even better with refs in 2014, when it made the first-ever formal playoff and won the national championship on Jan. 12, 2015.