WHEN AN EARNINGS RECESSION IS NOT ACCOMPANIED BY A RECESSION

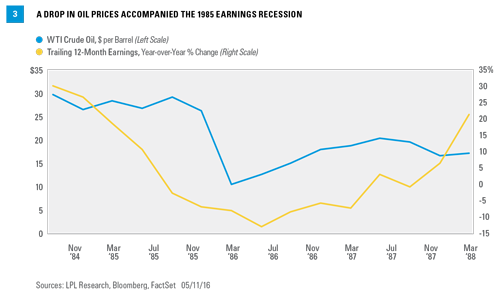

There are only three earnings recessions—one in 1967, one in 1985, and today's—that were not related to an economic recession. Both the 1967 and 1985 earnings recessions happened during periods in which the federal government deficit was increasing, while today the deficit is actually shrinking. Interestingly, the 1985–86 earnings recession was also accompanied by a steep and sudden drop in the price of oil, and took place during a relatively long economic expansion from 1982–1990 [Figure 3].

Earnings recessions that don’t accompany economic recessions have historically caused less pain for the stock market; however, given that the two don’t always happen simultaneously, how can investors be sure that an economic recession is not on the way? No method is perfect, and the sample size is small, but three indicators can help assess whether an earnings recession may be accompanied by an economic recession.

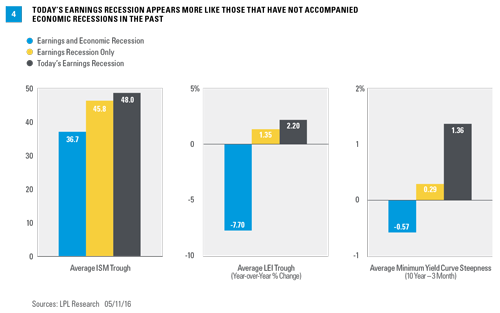

The degree of decline in the Institute for Supply Management’s (ISM) reading on manufacturing activity, the yield curve, and the annualized change in the indicators in the Leading Economic Index (LEI) show marked differences between an isolated earnings recession and a full-blown economic recession [Figure 4]. The ISM is particularly insightful because it has historically led earnings by about six months.

The yield curve has historically inverted prior to economic recessions, and the year-over-year growth rate in the LEI also tends to turn negative. Taken together, these indicators suggest that today’s earnings recession is not likely to be followed by an economic recession.

The number of sectors experiencing an earnings recession may also be an indicator, but data are only available dating back to the early 1990s. Of the three recessions since that time, two maxed out at seven sectors in earnings recession, and one (2008) maxed out at eight sectors, again pointing to the narrow nature of today’s earnings recession.

Are Earnings Recessions An Opportunity?

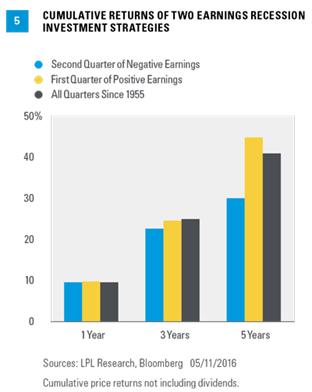

The bigger question may be, is it better to invest during an earnings recession or outside of one? Figure 5 shows the median results of investing using two different strategies surrounding earnings recessions: investing at the end of the second quarter of negative earnings (the official start of an earnings recession), and investing at the end of the first quarter of positive earnings following an earnings recession. As a comparison, the figure also shows the median return of investing two months after the end of any given quarter since 1955. The returns for all three strategies assume investing two months after the end of the appropriate quarter, as it would be impossible to know if either event is happening until earnings are reported.

Based on historical data back to 1955, buying during the first quarter of positive earnings is the most profitable over the one- and five-year time frames, though the five-year number is more impactful; three-year returns were also in-line with the all quarters' median. Investing after the second quarter of negative earnings was the second best over a one-year period, but was the worst of the three options over three- and five-year time horizons. Although it does appear that investing after earnings recessions has been beneficial historically, it is also important to keep in mind that these results are based on a small sample of only 11 earnings recessions (not including the current), and results will likely vary in the future. However, the chart does reinforce the long-term impact of earnings growth on stock prices.