Key Points

-

Emerging market (EM) bonds have performed strongly so far this year, as loose monetary policies in the developed world have driven yield-seekers into new markets.

-

We believe investors should be cautious as rising debt levels and slow global growth raise the risk of defaults or losses in the EM bond market.

-

EM bonds can provide diversification benefits, but we suggest investors have no more than a strategic allocation to such bonds.

After several years of mixed results, emerging market bonds—whether denominated in U.S. dollars or local currencies—have delivered positive total returns so far this year. The total return for the Barclays Emerging Markets USD Aggregate Bond Index is 12.6% this year, while the Barclays Emerging Markets Local Currency Government Index has delivered a 14.6% return.1

Those results have been driven by the downward shift in expectations about the pace of rate hikes by the U.S. Federal Reserve and very easy monetary policies in Europe and Japan. Returns from local-currency EM bonds have also received a fillip this year from high coupons and gains in EM currencies like the Brazilian real and Russian ruble. (Remember, gains in a foreign currency boost returns from that country’s bonds when they’re converted into U.S. dollars.)

With investors searching for income, the relatively high yields on EM bonds compared with those in other markets have begun to attract buyers. Inflows into EM bond funds have been strong in the past month. According to Morningstar, inflows to EM bond funds in July amounted to $2.8 billion, the largest monthly inflow ever recorded.

However, we would advise caution before joining the fray. First of all, currency fluctuations have actually been a problem for local currency bonds in recent years. They could also be an issue going forward as EM corporate borrowers have gorged on U.S. dollar-denominated debt in recent years. And, finally, EM bond prices may have been pushed to the point where they aren’t offering enough compensation for the risks involved.

Currency Question

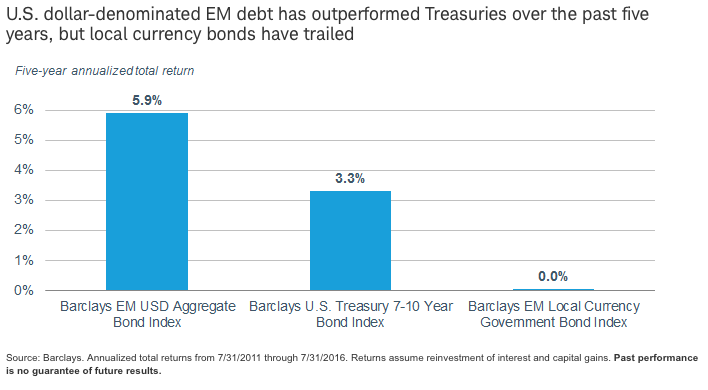

EM bonds denominated in U.S. dollars have done well over the past five years when compared to U.S. Treasuries of comparable maturities, as you can see in the chart below. Dollar-denominated EM government debt, in particular, has performed well as low global interest rates have helped push yield-seekers into new markets.

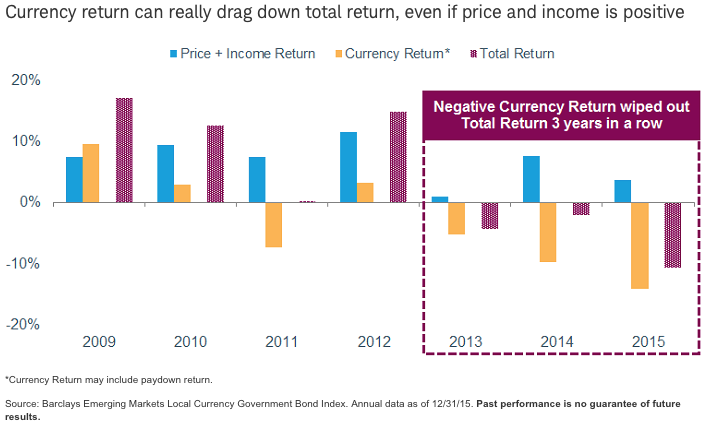

The same can’t be said for local currency EM bonds. Average returns from such debt have actually been flat over the past five years, largely because currency losses have offset price increases. As you can see in the chart below, currency weakness actually wiped out any returns from local currency EM bonds in the last three years.

Corporate Debt Binge

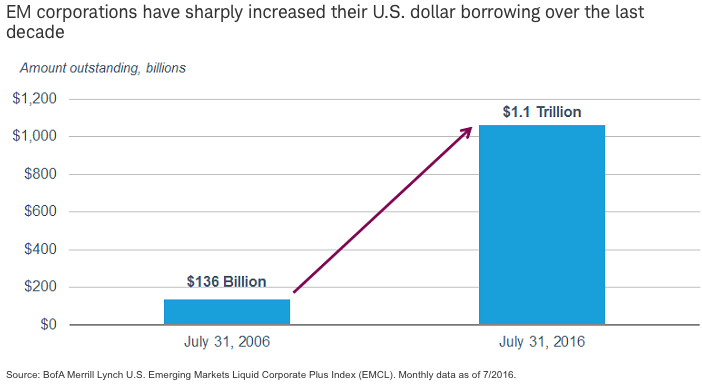

Meanwhile, corporate borrowers in emerging markets have loaded up on U.S. dollar debt in recent years, as low interest rates have given them access to cheap funding. About 46% of the nonbank corporate borrowing in EM countries is denominated in U.S. dollars, according to data from the Bank for International Settlements (BIS). 2 That kind of borrowing can make sense if a borrower’s revenues are denominated in dollars because it is a natural hedge. However, if most of a borrower’s revenue is some other currency, then a stronger dollar could make it harder to repay debt.

According to the BIS, between now and 2018 repayments will rise by 40% compared to the previous three years. And if the U.S. Federal Reserve raises interest rates later this year, which we think is a possibility, some companies that borrowed in U.S. dollars may have difficulty refinancing their debts if the dollar rallies on higher interest rates. That is especially worrisome given the very sluggish pace of global growth.

Higher interest rates in the U.S. could also pose a problem for U.S. dollar-denominated EM bonds, as higher rates could entice some bond investors back to the U.S.

Highly Valued

Valuations are also a consideration. EM bonds can provide diversification benefits to a fixed income portfolio. However, the higher risks involved (compared to developed market or domestic bonds) should mean investors in such bonds should receive more compensation in the form of higher yields.

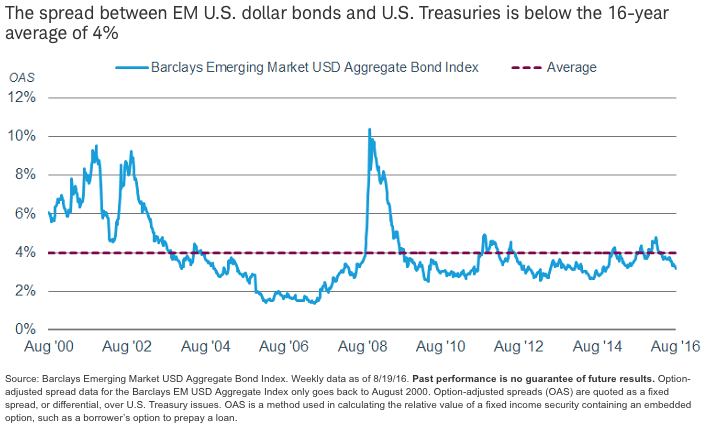

That doesn’t appear to be the case now. The current yield spread between U.S. dollar-denominated EM government bonds and U.S. Treasuries of comparable maturity is 3.15%—well below the 16-year average of 4%.3 The spread between local currency EM bonds and U.S. corporate bonds of similar maturity is 2.4%, which is right in line with the long-term average spread.

Given these conditions, we would caution investors about adding to the EM bond holdings in the hope of reaping more of the returns we’ve seen so far this year, especially with the potential for the Fed to raise interest rates later this year. The risks of currency losses and/or corporate defaults appear to be rising.

We suggest limiting the holdings of EM bonds to no more than the strategic allocation level. Investors in more aggressive areas of the fixed income markets, including EM bonds, should have a long time horizon if they want the diversification benefits. They should also avoid trying to time the market.

1As of August 19, 2016.

2 “Emerging Markets’ Bills are Coming Due,” Wall Street Journal, August 19. 2016.

3Option-adjusted spread data for the Barclays EM USD Aggregate Index only goes back to August 2000. Option-adjusted spreads (OAS) are quoted as a fixed spread, or differential, over U.S. Treasury issues. OAS is a method used in calculating the relative value of a fixed income security containing an embedded option, such as a borrower’s option to prepay a loan.

Kathy A. Jones is senior vice president and chief fixed income strategist at Schwab Center for Financial Research.