With our baseline view of 2%–3% nominal growth over the next three to five years, Europe’s economic, fiscal, social and political environment will remain fragile. Investors should be cautious.

While the eurozone recovery has been gaining momentum over the past three years, its pace has disappointed in light of declines in GDP from 2008 to 2013. Eight years after the financial crisis, real output is still flat relative to its pre-Lehman peak. In contrast, output in the UK and the U.S. is about seven and 10 percentage points above pre-crisis levels, respectively.

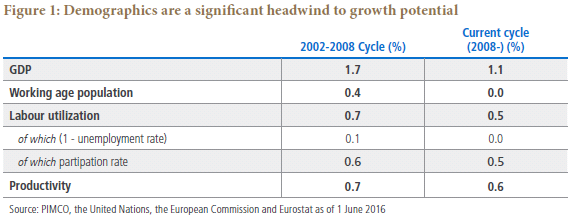

Unfortunately, prospects over the three- to five-year secular horizon do not look much brighter. For a start, growth potential remains on a steadily sliding path. To assess potential, we use a simple growth accounting framework that breaks GDP into demographics, labour utilization and productivity. As Figure 1 shows, working age population growth is slowing meaningfully, with demographics alone set to shave nearly 0.5 percentage points off growth in the cycle that began in 2008 (relative to the previous cycle of 2002–2008). What’s more, the damage to labour markets and investments caused by the recent double-dip recession suggests that labour utilization (employment/working age population) and productivity (output/employee) are also likely to contribute less to growth than a decade ago. Putting this together, the eurozone’s growth potential is probably close to 1%, down from about 1.75% a decade ago.

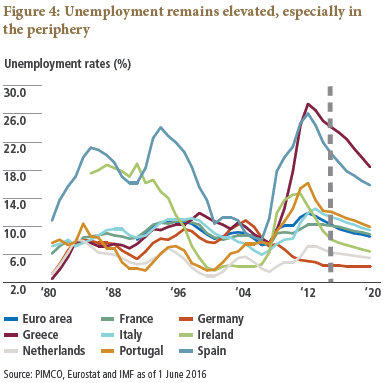

It’s hard to be encouraged by this kind of macro outlook in light of the huge deterioration of the labour market that’s taken place since 2008. Since then, the eurozone unemployment rate has risen nearly five percentage points to a peak of 12% in 2013, and remains above 10%. The spike in unemployment in the periphery has been especially noteworthy, with jobless rates in Spain and Greece now close to 20% and 24%, respectively.

The slow recovery means not only that social pressures will remain elevated, but also that economic slack will erode slowly. The output gap in Europe will not be closed until late in our secular horizon, and the European Central Bank (ECB) will likely miss its “below but close to 2%” inflation target for the foreseeable future. We see inflation averaging about 1.25% over the coming five years.

Faced with low growth, weak inflation, high real debt and social and political pressures – plus little to no appetite for further regional integration – pressure will remain on the ECB to maintain a very stimulative stance.

Weak macroeconomic growth momentum, a shaky institutional setup and elevated political risk suggest that investors should tread cautiously when placing money in Europe over the medium term, and treat capital preservation as a priority.

Nicola Mai is an executive vice president in PIMCO's London office and a sovereign credit analyst in the portfolio management group.

Of course, there is scope for the eurozone to grow above potential in coming years. In particular, the depressed level of GDP and domestic activity suggests that some pent-up demand could emerge; extremely stimulative monetary policy has led to significant improvement in financial conditions and some revival of the credit cycle; and, after years of austerity, fiscal policy is now modestly stimulative.

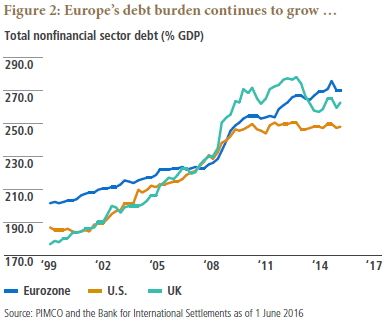

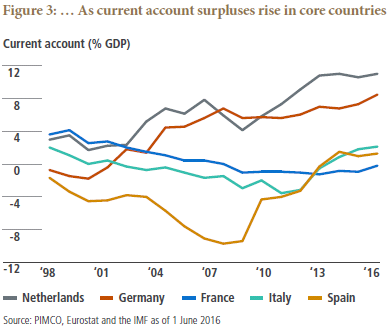

But it’s hard to get excited about the ongoing cyclical revival, which remains saddled with structural headwinds. First, as Figure 2 shows, total leverage (household, nonfinancial corporate and government) is high and still rising. At 270% of GDP, it is higher than both the U.S. and the UK, where total leverage is being contained by successful private sector deleveraging (private sector leverage in the eurozone has remained stable at a high level). Second, the eurozone continues to suffer from the lack of an internal demand engine. In particular, parts of the region that are less indebted and could afford to spend (first and foremost, Germany) continue to fail to boost domestic demand. This is evident in the ever-rising current account surplus in countries such as Germany and the Netherlands, now close to 8% and 11% of GDP, respectively (see Figure 3). Third, geopolitics remains a source of risk in Europe, driven by rising populism, the refugee crisis, terrorism and a dysfunctional decision-making process in Brussels. A political backdrop of this sort weighs on economic confidence and investment.

Putting this together, we expect real GDP will grow only marginally above potential over the secular horizon – by about 1.25% per year. And even this outcome is far from guaranteed due to the economy’s vulnerability to external shocks.

Social and political risks to remain elevated

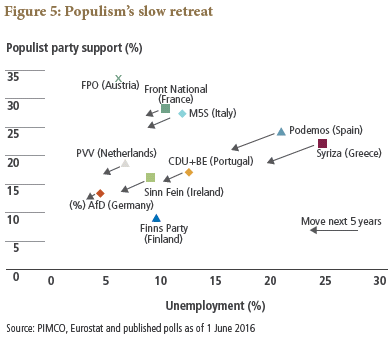

Our analysis of the relationship between growth and labour market developments in the eurozone suggests that unemployment rates should fall in coming years, but only gradually. As Figure 4 shows, many peripheral countries are expected to be still experiencing double-digit unemployment rates at the end of the secular horizon.

Extended high unemployment will have deep implications. Social tensions are likely to remain elevated, as will support for populist parties in the region – broadly defined as movements that are opposed to the establishment, immigration and globalization, sceptical of Europe and in favour of looser fiscal policy. As Figure 5 shows, falling unemployment will lower populism according to our estimates, but only marginally so.

The persistence of populism means that eurosceptic feelings are here to stay, and that further institutional integration in Europe – in fiscal, political and financial market arenas – is likely to be limited, if not zero, in the years ahead.

Persistently low inflation to keep debt burdens elevated

Low inflation means the region will remain vulnerable to a slide into deflation when the next economic shock hits. And importantly, it will keep the real level of public and private sector debt burdens elevated, reinforcing the need for financial repression.

ECB: The only “glue” in what will feel like a fragile equilibrium

The central bank’s quantitative easing (QE) program, which is scheduled to end in March 2017, is likely to be extended and continue over much of the secular period. The ECB could broaden the range of assets it buys and relax some of its buying rules – abandoning, for example, the requirement to buy sovereign bonds from different countries in proportion to the ECB’s capital key. Coupled with a modestly expansionary stance by the fiscal authorities across the region, ECB QE could be seen as an implicit form of fiscal monetization over the secular horizon.

When thinking about the secular outlook, there is also the question of how the eurozone would deal with the next economic shock, were one to hit in coming years. With the efficacy of monetary policy clearly diminishing, fiscal policy would likely need to take a more active role. The constraints posed by overextended public sector balance sheets in peripheral countries, however, would make the ECB’s role as implicit lender of last resort for sovereigns in the region all the more important. It is possible that implicit monetization could become more explicit, although populism and Treaty limitations concerning direct financing of governments could prove to be constraints for the ECB.

Overall, the ECB remains a key pillar for regional stability, but will feel increasingly overburdened. The eurozone will continue to feel stuck in a fragile equilibrium.

Maintain caution when investing in Europe

We are broadly neutral high quality (investment grade) credit and large (Italy/Spain) peripheral sovereign bonds versus benchmarks, after years in which we were overweight. The neutral position is a compromise between what we see as a challenged secular outlook and ongoing significant monetary support.

For our portfolios focused on liquidity, we are particularly cautious about going down the capital structure and investing in illiquid, lower-quality instruments such as small peripheral sovereigns or higher-risk corporate bonds. The uncertain economic and political backdrop plus the broad legal uncertainty in the region (as evidenced by the haircuts given to Heta Asset Resolution and Novo Banco bonds over the past year) raise the bar for investing in these areas.

For core bonds, it is hard to like duration in Europe with 10-year bund yields close to or dipping below zero. Low inflation and central bank engagement, on the other hand, leave room for keeping some duration risk in portfolios, focused on intermediate maturities where carry and roll-down is most attractive. In currency markets, we see the euro moving sideways over the secular horizon, as the boost from a sizeable current account surplus is offset by the depressing effect of rising political risk premia. Finally, in equity markets, there’s room to be tactical, but caution is warranted overall given economic and political risks in the region.

In sum, challenging politics and idiosyncratic risks in Europe suggest that investors should be cautious, but also ready to seize opportunities arising from potential market dislocations. Blindly following benchmarks would likely be particularly dangerous in this environment. In contrast, active asset managers have the potential to add value by differentiating across names in the credit and sovereign space, hedging against tail risks, and tactically moving in and out of positions in an effort to exploit periods of high volatility.