Are 3.5% yields on floating-rate senior loans exposing clients to too much credit risk?

Apparently, investors don't think so. In the first quarter of 2011, more than $10 billion flowed into mutual funds that invest in floating-rate senior loans, according to Lipper, New York.

Senior floating-rate loans are short-term collateralized loans made by financial companies to corporations with below-investment-grade credit ratings. These debt instruments also go by the rubrics of "bank loans" or "syndicated floating-rate bank loans." The loan's interest rate typically resets every 30 to 90 days, based on changes in the London Interbank Offered Rate (LIBOR). The interest rate is based on the LIBOR rate plus a spread to compensate lenders for the credit risk.

Although there is a risk the creditor may default, there is little market interest rate risk because the loan interest rates are reset periodically. The average duration of a portfolio of the holdings in senior loan mutual funds is less than one year, and their average maturity is about four years, according to Morningstar Inc., Chicago.

In addition, the loans are collateralized by the borrower's assets. Investors get paid before holders of subordinated bank loans, bondholders and stockholders if the company defaults.

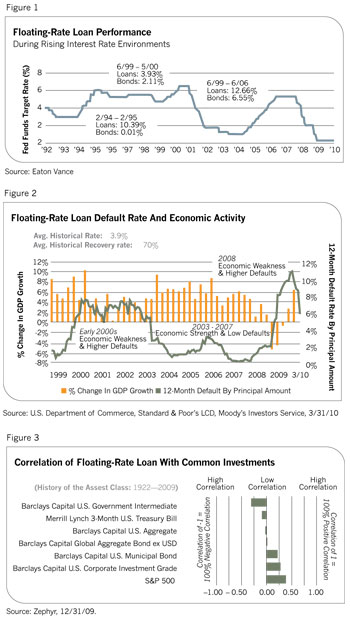

Over normal business cycles-unlike the one in 2008 that triggered a financial market collapse and frozen credit markets-senior loans have performed well.

But financial advisors, despite the growing popularity of these investments, need to scrutinize the risk-return trade-off of including these floating-rate loans in client portfolios.

"The trade-off for that attractive interest rate profile and generous income potential is a healthy dose of credit risk," says Morningstar fixed-income director Eric Jacobson. "That's because the portfolios in this category almost exclusively invest in yield-rich debt of highly leveraged loans." The leverage, he says, refers to the debt on the issuer's balance sheet rather than margin loans by the mutual funds that hold them.

Robert H. Dial, manager of the Mainstay Floating Rate fund, recommends that financial advisors view senior floating-rate loans as a separate asset class because of their low correlations to stock, high-grade corporate bonds and U.S. Treasury bonds. "Floating-rate loans should not be considered an alternative to money market securities, money market funds or certificates of deposit," he stresses. "They are a short duration alternative to high-yield bonds."

A portfolio's risk-adjusted rate of return improves when floating-rate senior loans are added to T-bills, bonds and stocks, according to a working paper led by Kam Chan, finance professor at Western Kentucky University, Bowling Green. The paper, "Bank Loan Funds: Investing Beyond T-bills," assumes that an investor initially invested 100% in T-bills, with bank loan open-end mutual funds and other assets added to the mix with return requirements ranging from 5% to 10% for the years 1990 to 2005. As return requirements rise, bank loan fund allocations rise and standard deviations fall. But to obtain portfolio returns of substantially more than 8%, higher allocations to equities and high-yield bonds are necessary.

Craig P. Russ, co-manager of the Boston-based Eaton Vance Floating Rate Fund and the Eaton Vance Floating Rate Advantage Fund, believes that today's market should follow historical business cycle norms. Credit fundamentals continue to improve and loan defaults are below average.

"Companies in our marketplace have experienced six consecutive quarters of revenue and profit growth," Russ says. "Cash flows are up substantially over a year ago. Default rates are under 2% after peaking at 11% in 2009."

Dial, of Mainstay, says the market for senior loans looks appealing today. Many loans are priced at par and the best credits are trading at a premium. He believes interest rates are likely to rise next year. So longer duration bonds could lose money. But floating-rate funds can be one way to get enhanced yield over a Treasury bond or a high-grade corporate fixed-income investment without extending duration.

"We have a positive view of where credit spreads are today, as well as the prospects for the floating-rate asset class over the next year," Dial says. "As measured by the trailing-12-month default rate, the leveraged loan market continues to improve. Contributing to the improvement is the fact that many of the most troubled issuers already have defaulted, while improved market liquidity has helped others remain solvent."

Dial steers the fund into higher quality 'BB'-rated loans. Companies such as Community Health Systems Inc., Health Care Corporation of America, Celanese Corp. and Graham Packaging have good cash flows and a history of high debt coverage ratios.

Russ, of Eaton Vance, also favors 'BB' and 'B'-rated credits that have strong cash flows and debt coverage ratios. He took advantage of cheap loan prices during the market collapse to add to his positions in strong companies. He's also invested in well-managed companies that have less stringent loan covenants, such as J. Crew, the clothing retailer; NBTY, a large vitamin manufacturer; and CommScope, a coax and fiber cable company.

Dial and many other fund managers also have small positions in these types of investments, which are called "covenant lite" senior floating-rate loans. Published reports indicate that these loans make up about 25% of the market.

The largest holdings of Eaton Vance's two senior loan funds include companies with inelastic demand for their products and services, such as Community Health Systems, Hospital Corporation of America, UPC Broadband, Charter Communications Operating and SunGard Data Systems.

Most senior loan mutual funds, such as Mainstay and Eaton Vance, have larger positions in companies that have bank revolving lines of credit. And the funds review loan covenant contingencies quarterly to make sure the firms adhere to cash flow and debt coverage guidelines. Collateral tends to be hard assets like inventory, receivables or subscriber values in the wireless communication industry.

Research shows that senior floating-rate loan fund portfolios are on the right track with active management because this market can be highly inefficient. A 1995 Journal of Portfolio Management study, "Corporate Loans as an Asset Class," by Elliot Asarnow, currently chief operating officer of BlackRock Private Equity Partners, New York, suggests that financial advisors should tactically allocate senior loan funds to a client portfolio. The study found that an actively managed portfolio of floating-rate corporate loans displaced Treasurys and high-grade corporate bonds in low-to-medium-risk, multi-asset-class portfolios.

Other financial research reveals that during periods of rising interest rates, the Credit Suisse Leverage Loan Index performs well. In the rising rate period of February 1994 through February 1995, floating-rate senior bank loans gained 10.4% compared with .01% for bonds, according to research by Eaton Vance. Meanwhile, in the rising rate period of June 1999 through May 2000, senior floating-rate loans gained 3.9% while bonds gained 2.1%.

In the more recent rising rate period of June 2004 through June 2006, senior floating-rate loans gained 12.7% while bonds gained 6.6%.

There is no free lunch. During periods of declining interest rates, advisors may have to adjust their senior loan fund positions. That's because bank loans don't fare as well as high quality bonds.

A study by the Financial Planning Association of Southern Wisconsin reports that during 2001 and 2002, when bonds and mutual funds were performing well, floating-rate senior loan funds barely broke even. Defaults hurt floating-rate senior loan funds during those times.

Advisors also need to monitor the duration of their overall fixed-income portfolio when it includes senior floating-rate loans. The duration of floating-rate loans can change as credit risk changes, according to a study, "The Pricing and Duration of Floating-Rate Bonds," published in the 1987 Journal of Portfolio Management. Jess Yawitz, its senior author, is chairman of NISA Investment Advisors, St. Louis.

Market technical problems also are a variable to consider when investing in these loans. Eighty percent of more than $600 billion in senior floating-rate loans issued by 1,600 companies are held by institutional money managers, including hedge funds and collateralized loan obligations.

Russ, of Eaton Vance, says that during the financial collapse, the credit markets froze. Margin calls and market value triggers forced the liquidation of creditworthy assets across asset classes. And in 2008, published reports indicate about 175 issuers defaulted on $125 billion in loans. Investors recovered just 60 cents of every dollar on defaults.

It is important to monitor the volatility of senior loan mutual funds. There was little liquidity in the senior loan market during the financial crisis, so volatility increased swiftly and dramatically. As a result, financial advisor asset allocation models may have failed to adjust for the risk.

In the period before the collapse of Lehman Brothers, from January 2000 to September 2008, the Credit Suisse Leverage Loan Index grew at a rolling five-year annual rate hovering around 5%, with a standard deviation of 2% to 4%, according to a report by Babson Capital, Norwalk, Conn. After the Lehman default, the standard deviation on the loan index return doubled to 8%. Loan returns declined at nearly -5% annually, based on five-year rolling returns from January 2000 through June 2010.

Financial advisors should do their credit homework before they invest in senior loan mutual funds, closed-end funds or exchange-traded funds, suggests a working paper led by Hinh Khieu, assistant finance professor at the University of Southern Indiana, Evansville, Indiana. His research of senior loan defaults over the past 20 years reveals that companies with high levels of overall debt on their books and poor quality collateral resulted in investors recovering less after a default.

"Firm leverage before default negatively affects ultimate recoveries, while borrower cash flows do not," he says. "Firm size influences recoveries differently across different types of loans. A variety of loan contract features are strongly related to the ultimate payoff for creditors. Secured loans have higher recoveries, and among the types of collateral, inventories and accounts receivable result in the highest recoveries. Prepackaged bankruptcy reorganization increases actual settlements."