For decades, a growing pool of college graduates poured into the U.S. labor market, boosting productivity and shaping America’s status as the world’s dominant economic power.

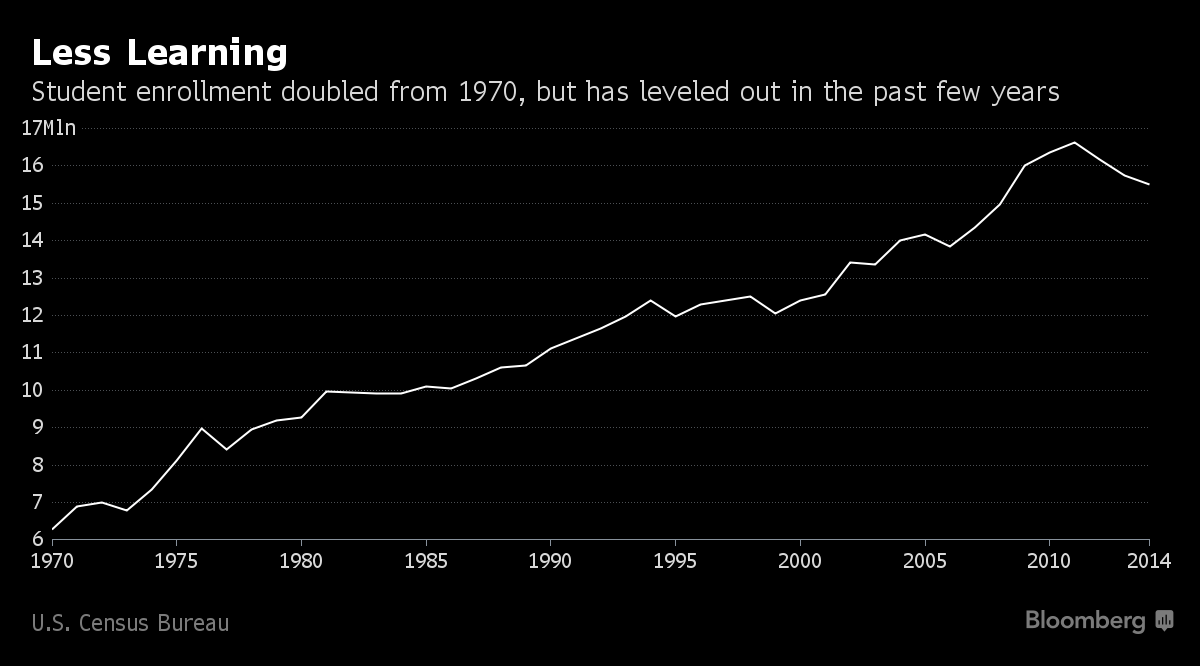

That driver of growth is diminishing. Enrollment has declined every year since peaking in 2011, according to the Census Bureau and the National Student Clearinghouse Research Center. The reasons include an aging population, rising tuition costs and a healthy rate of hiring that lessens the demand for learning.

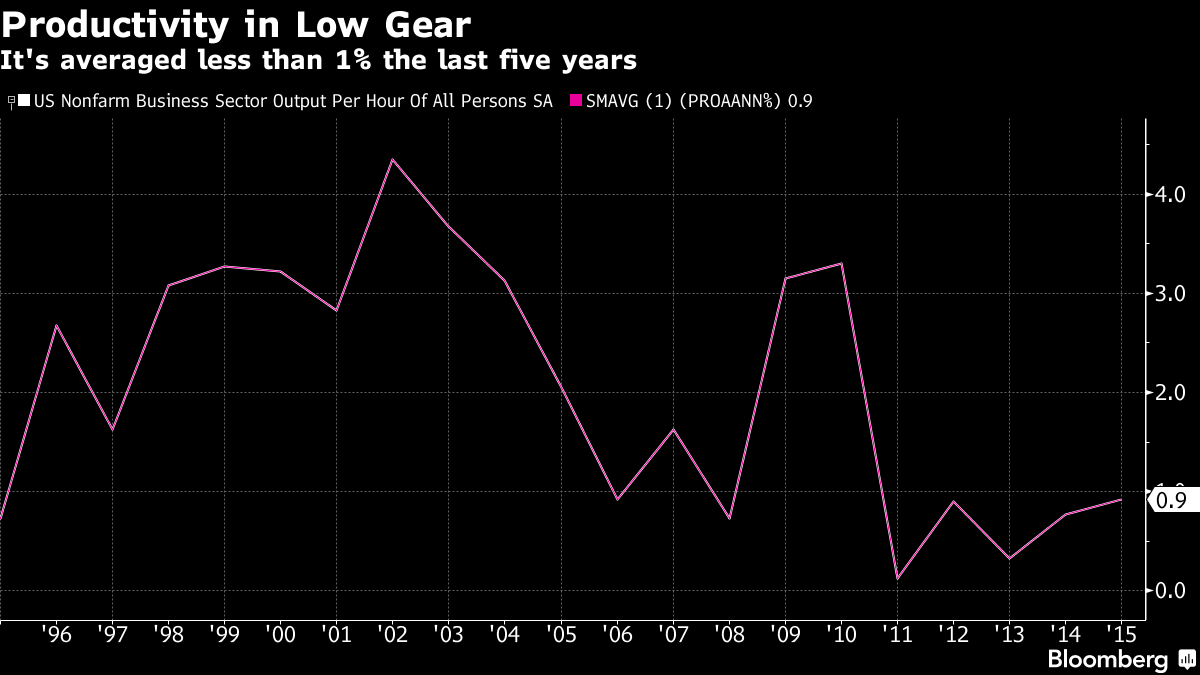

Lamenting the end of the so-called productivity miracle are Federal Reserve officials and economists more broadly, who hailed its ability to allow faster growth without harmful inflation. Now, central bankers largely powerless to fix the schooling slump say something must be done to counter it to prevent a new era of weaker growth.

“As a society, we should explore ways to raise productivity growth,” Fed Chair Janet Yellen said last month at an economic symposium in Jackson Hole, Wyoming, adding that it’s worth considering “improving our educational system and investing more in worker training.”

Among the most noticeable consequences of weaker college enrollment is lower wages. Higher education leads to better-paying jobs -- graduates, on average, earn about 90 percent more than non-graduates, but only about a third of Americans get degrees. Workforce quality, which along with technology, helped American employers boost productivity in the 1980s and ’90s, now appears to be contributing to anemic efficiency gains that could continue.

“Slow growth in educational attainment is one of the headwinds,” said Lawrence Katz, a Harvard University economist who was the U.S. Labor Department chief economist in during Bill Clinton’s administration. “The quantity and quality of schooling are important issues for direct effects on productivity -- more educated workers are more productive -- and for indirect effects on the pace of innovation and adoption of new technologies.”

Katz estimates the direct impact of less-educated people joining the workforce has the potential to reduce productivity by 0.25 percentage point a year, and create snowballing indirect effects that hold back innovation.

Productivity as measured by employee output per hour has fallen for three straight quarters, the Labor Department reported last month. Productivity growth has averaged 0.4 percent since 2011, after averaging 1.9 percent in the 1980s and 1990s.

Less-educated workers have fewer career options, even as slack in the labor market is evaporating and the economy edges closer to restoring full employment. The unemployment rate for those with a high-school diploma was 5.1 percent in August, compared with 2.7 percent for those with a bachelor’s degree or higher. For those with less than a high-school degree, the jobless rate was 7.2 percent.

Darrell Jackson, a 31-year-old in Atlanta, says having just a high-school diploma probably closed doors for him in the job market. Jackson said he’s applied for about 50 positions and landed no interviews in the three weeks since losing his job as a parking garage maintenance worker. He’s now considering an online training program to boost his skills.