In mid-June, all the Federal Reserve’s 17 senior officials expected at least one increase in short-term interest rates by the end of the year and most were looking for two. Bear in mind, that outlook followed a weak initial payroll figure for May. In contrast, the financial markets have mostly priced out a Fed move for this year. Is the Fed trapped?

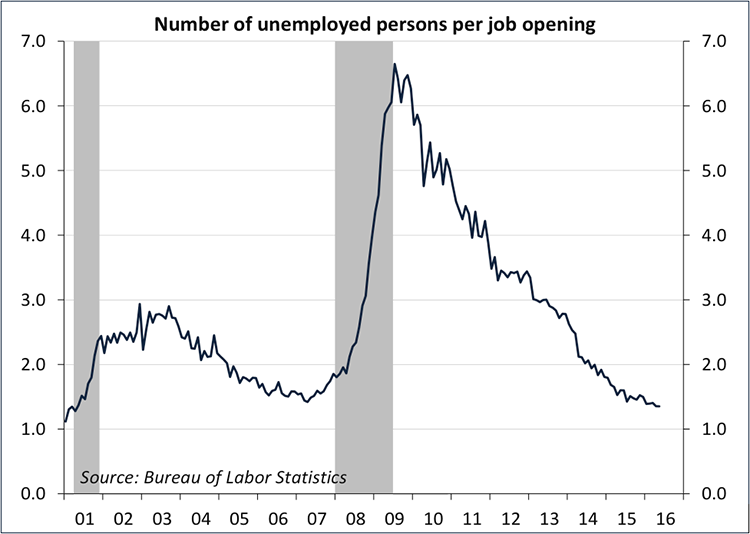

Yet, it’s not past inflation that the Fed is worried about. Monetary policy is concerned with future inflation. Inflation is a monetary phenomenon, but we observe it through pressure in resource markets. Commodity prices are low, but seem unlikely to fall much further. There is excess capacity in manufacturing, so we aren’t going to see bottleneck inflation pressures developing anytime soon. The labor market is the widest channel for inflation pressures and is clearly the greater focus for the Fed. While there are signs of slack in the job market, conditions have grown tighter, and the Fed anticipates further improvement in the months ahead. Wage pressures have remained moderate, but many Fed officials expect stronger wage gains in the months ahead. State and local minimum wage increases may also add to pressures over the next few years.

A broad acceleration in wages need not be something for stock market participants to fear. Labor-intensive firms will face higher costs, but consumer demand (and overall economic growth) ought to be higher. In the late 1990s, the Fed, led by Alan Greenspan, tested how far the labor market could go. The unemployment rate fell, but that understated the strength, as labor force participation rose. Job losses were unusually elevated in the late 1990s, but job creation was even stronger. It was an unusually transformative time for the U.S. economy.

Given the current backdrop, getting the balance right is likely to be more challenging. The population is aging. Job turnover is going to be slower. Productivity growth has slowed and may not pick up again, which means that wage increases would become a greater restraint on earnings growth. Stronger wage gains would likely lead to some restructuring of the economy. The markets should be considering the long-term uncertainties, but there’s strong hope that things are going to turn out okay.

Scott J. Brown, Ph.D., is chief economist at Raymond James & Associates.

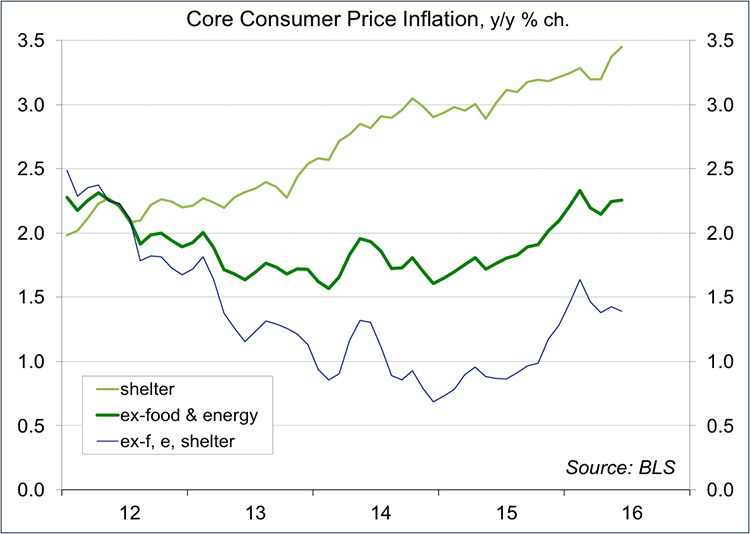

At the consumer level, inflation pressures appear to be mostly consigned to shelter and healthcare. No surprise, the strong job gains of the last few years have fueled housing demand. Home prices are rising. However, in the CPI calculation, the BLS seeks to separate the asset value of a home from the service it provides (shelter). So, it substitutes the rental equivalent for homeowners. Homeowners’ equivalent rent, which accounts for nearly a quarter of the CPI, rose 3.2% y/y, while rents (for actual renters) rose 3.8%. Core inflation (which excludes food and energy) rose 2.3% y/y, but if you exclude shelter, it would have risen 1.4% y/y. Bear in mind that the Fed uses the PCE Price Index as its chief inflation gauge, which is trending well below the CPI over the last several months.

One question Fed officials should be asking themselves is whether firms will be able to pass along wage increases or be forced to absorb them. In the Great Inflation of the 1970s and early 1980s, union membership was a lot higher than it is now and labor’s position in wage bargaining was a lot stronger. Wage growth responded quickly to increases in prices. Inflation soon became imbedded in the labor market, and wringing inflation expectations lower was costly (a major recession in the early part of the 1980s). Hence, many Fed officials see their main task as “keeping the inflation genie in the bottle.” However, Fed Chair Yellen may be more inclined to let the labor market run for a while. Stronger wage growth means stronger income growth, and stronger consumer spending (provided that the wage gains are not offset by higher prices). Views on wages and prices aren’t binary. There will be a range of opinion amongst Fed officials on how much pass-through we may see. Moreover, pass-through ability is likely to change over time.