Your new financial advisor has a well-decorated office, a firm handshake, and a bright smile. After an hourlong meeting, you leave with what you think is a state-of-the-art investment portfolio. You feel financially secure, taken care of.

It’s also possible you’ve made a huge mistake. The White House under President Barack Obama estimated that Americans lose $17 billion a year to conflicts of interest among financial advisors. Wall Street lobbying groups dispute that math—and they’re right to do so. The actual dollar amount is probably much higher.

A wave of research over the past few years has documented serious problems with how Americans get financial advice. Susan Shaffer, a 70-year-old retiree in Narberth, Pennsylvania, learned this the hard way as she hired and fired multiple advisors over two decades. One chose inappropriate investments, including small-cap stocks. Another put her into funds with huge, back-loaded fees. The third promised to charge just $500 a year, then stuck her with thousands of dollars in commission costs.

Each time, Shaffer did her own research. She took classes, pored over dense account statements, and generally did the work she was paying her advisor for. “You have to keep watching everything. You’re very vulnerable,” said Shaffer, who retired three years ago after a career in the pharmaceutical industry. “Nobody really had my interests at heart.”

Consumers like her say that’s the real problem: Many financial advisors just don’t care what’s best for you. But with an industry awash in misconduct, the bigger issue may be that they aren’t required to care.

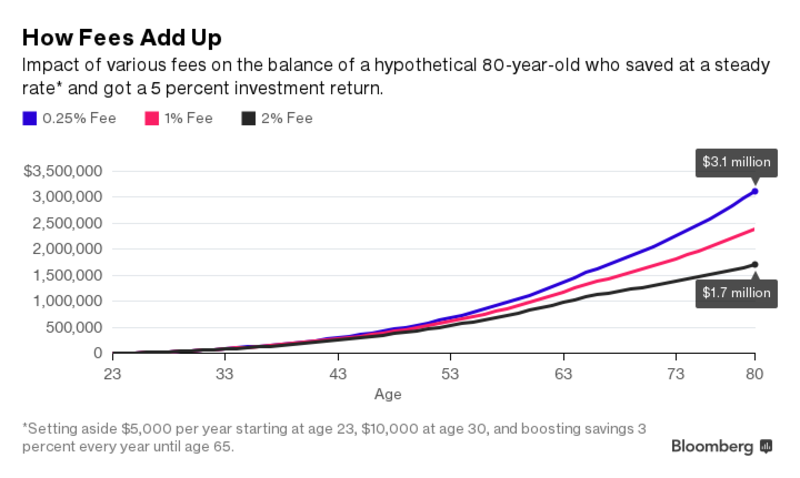

You’d be forgiven for assuming your relationship with a financial advisor carries the same sort of solemnity as, say, attorney and client or doctor and patient. An attorney is bound to zealously represent you; a doctor pledges to do no harm. So why aren’t financial advisors subject to the same duty? Well, the economics of the industry—fees, commissions, quotas—can end up standing in the way.The Fiduciary Rule, finalized under Obama and originally set to take effect earlier this year, seeks to cure this disconnect. All advisors were to be required to put clients first when handling retirement accounts, where the bulk of everyday Americans’ savings reside. But then Donald Trump won the election, and on his 15th day in office, the Republican president ordered the Department of Labor to reconsider the rule. His advisors echoed Wall Street arguments that tying the hands of advisors would limit investor choices, raise the cost of financial advice, and trigger a wave of litigation.

This Friday, the rule will take partial effect. Its future, though, remains deep in doubt. Many Republicans in Congress oppose it, and Labor Secretary Alexander Acosta has suggested that at the very least it be revised. Then last week, Trump’s newly appointed chairman of the Securities and Exchange Commission, Wall Street lawyer Jay Clayton, announced his agency would also seek comment on the topic, a process that could further threaten the rule’s survival.

While Washington wrestles with the fate of the Fiduciary Rule, the financial advice landscape remains supremely dangerous. Three professors recently analyzed a decade of disciplinary data on 1.2 million financial advisors. What they found is decidedly unpleasant:

• At the average firm, 8 percent of advisors have a record of serious misconduct.

• Nearly half of those 8 percent held on to their jobs after being caught. About half of the rest got jobs at other financial firms. In other words, a year after serious misconduct, about three-quarters of advisors found to have wronged clients are still working.