Even many central bankers admit that monetary policy is exhausted, and that fiscal policy should increasingly be the focus of efforts to stimulate the economy. When monetary policy has reached the limits of its effectiveness, economists sometimes refer to continued monetary easing as “pushing on a string.” Fiscal and monetary policies have both been employed globally to ameliorate the impact of the Great Recession. Most countries engaged in some form of fiscal stimulus in 2009–10. In the U.S., a combination of state budgetary restrictions and the federal budget sequestration led to fiscal contraction, which partially negated the impact of loose monetary policy. Both presidential candidates have made increased infrastructure spending and other forms of fiscal stimulus part of their economic plan.

TO PUSH OR TO PULL? THAT IS THE QUESTION

The debate over which government policies should be implemented to boost economic growth is often phrased in terms of a “string.” When monetary policy seems to have reached the limits of its effectiveness, which certainly seems to be the current case globally, monetary policy is said to be “pushing on a string”—a metaphor for ineffective action. Increasingly, policymakers are looking to fiscal policy to fix what ails the global economy.

But what do these terms mean? Monetary policy refers to the management of the money supply and interest rates within a country, or in the case of the European Union, across a number of countries. Monetary policy is set by central banks, for example the Federal Reserve (Fed) in the U.S., the European Central Bank (ECB) in Europe, or the Bank of England in the United Kingdom. These central banks are generally considered independent of the government, though some countries, most notably China, do not have this separation. Monetary policy also includes setting some of the rules regarding the availability of credit, typically through banks. The Chinese authorities often use changes in lending rules, such as the amount required as a down payment on property purchases, as a policy tool.

Fiscal policy refers to a nation’s taxation and spending policy, and is a function of its government, not a central bank or other agency. In this regard, fiscal policy is more directly impacted by politics and elections, whereas monetary policy is generally considered above the fray. Because fiscal policy is a function of politics, discussions quickly get heated. It’s important to remember that fiscal policy refers to both tax and spending policy, and tax cuts can be just as impactful as spending increases.

FISCAL POLICY TIED IN A KNOT

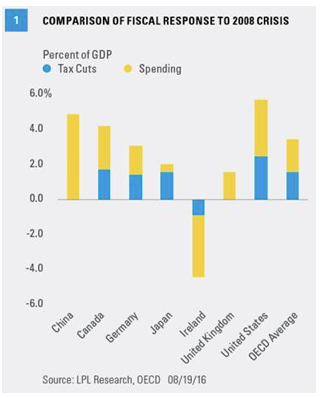

The initial response to the global financial crisis of 2008 consisted of coordinated monetary and fiscal policies. Interest rates globally were slashed, and in some countries, bank lending rules were eased. At the same time, most countries engaged in fiscal policy expansion. Figure 1 details some of these responses and the mixture of policy between tax cuts and spending. These policies were typically enacted over a period of years, with most of the impact felt in 2009–10, depending upon the country.

A few things stand out. Not all countries expanded fiscal policy; a few countries, like Ireland, engaged in austerity policies by raising taxes and cutting spending. China is also an outlier, as most of its policy response was done through the expansion of bank lending, which is technically part of monetary policy. In a country without an independent central bank and where the government is so entwined with the private sector, these sorts of distinctions become blurry at best.

Economists will debate for decades the effectiveness of these policies. But regardless of whether these policies were the most effective ways of preventing the kind of downward spiral seen in the 1930s, the global economy avoided the worst possible outcome from the financial crisis.

SIDEBAR – Accounting for Government Spending

When doing national income accounting (calculating things like GDP), government spending includes anything purchased by the government, from aircraft carriers to paper clips. It also includes salaries for government employees. But GDP does not include government spending in the form of transfer payments, that is, payments directly to individuals. This includes Social Security, Medicare, unemployment insurance, welfare programs, and similar types of spending.

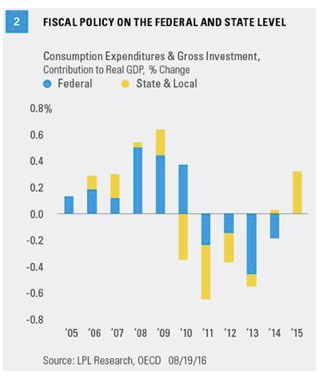

Fiscal and monetary policies did not stay aligned for long. Interest rates remained low, with most major central banks engaging in some form of quantitative easing (QE). Yet, fiscal policy tightened globally. This is especially true in the U.S. [Figure 2]. The U.S. is rare, globally, in that fiscal spending is done at both the state and federal level. Already by 2010, state and local spending were contracting. Most states have some legal provisions, either constitutionally or by statute, requiring a balanced budget. So whether there was a deliberate effort to cut spending, or there simply was a decline in revenue that necessitated a reduction in spending, fiscal policy on the state level began to counteract federal spending. If the intention of fiscal policy is to be “counter-cyclical”—to go against the trend in the economy—rigid rules like balanced budget laws defeat this purpose.

Fiscal spending on the federal level declined due to the budget sequestration section of the Budget Control Act of 2011, though the provisions did not become effectively until March 2013. More recently, states have begun to increase spending, partially because tax revenue has increased, but also because things like infrastructure maintenance and improvement can only be delayed for so long. Federally, sequestration is still in effect and creates some drag on U.S. gross domestic product (GDP).

Fiscal spending on the federal level declined due to the budget sequestration section of the Budget Control Act of 2011, though the provisions did not become effectively until March 2013. More recently, states have begun to increase spending, partially because tax revenue has increased, but also because things like infrastructure maintenance and improvement can only be delayed for so long. Federally, sequestration is still in effect and creates some drag on U.S. gross domestic product (GDP).

WILL EITHER CANDIDATE PULL THE STRING?

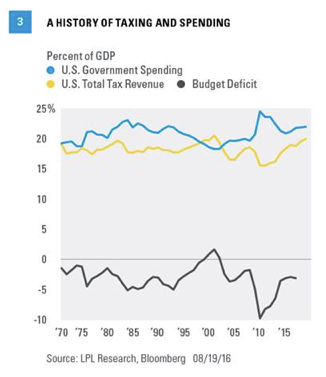

Both presidential candidates have invoked fiscal policy as a way to improve the U.S. economy, with some predictable similarities and differences between them. As the election nears, we are likely to get more details, and more rhetoric, from the candidates with regard to their proposed fiscal policies. The federal budget deficit has been growing in absolute terms; relative to GDP, the deficit has been stable at 2.8% of GDP and is expected to remain at this level for the next few years based on current trends [Figure 3]. As the candidates have promised to expand fiscal policy, the budget deficit is likely to increase in the near term, regardless of who wins the election.

One common fiscal policy proposal from both the candidates is an increase in infrastructure spending. Hillary Clinton has proposed $250 billion in additional infrastructure spending over the course of the next four years; Donald Trump has countered with $500 billion. Though neither camp provided details as to how that money would be spent, they do differ on how this spending would be funded. Trump has proposed borrowing these funds. Clinton has proposed creating a national infrastructure bank, funded from changes to the corporate tax code, likely from closing loopholes and changing the structure of the tax code, rather than raising rates. Though these numbers sound big, assuming the spending would occur during the course of a four-year presidential term, Clinton’s plan would amount to 0.25% of GDP, Trump’s to 0.5%, nowhere near the big numbers seen in the immediate response to the crisis.

Another likely change in fiscal policy will be tax reform, particularly for corporate taxes and some provision to encourage the repatriation of the over $2 trillion U.S. companies are holding overseas to avoid taxes. There is broad agreement in both parties that the tax code needs to be reformed, with lower rates and fewer exceptions and loopholes. The details of these reforms will be determined as much by the makeup of Congress as the identity of the next President. Either way, we would expect tax reform to be a source of fiscal stimulus after the election.

CONCLUSION

There is broad consensus, globally and in the U.S., that fiscal policy is going to be revamped to boost the global economy. Monetary policy has done all it can. Concerns about the budget deficit and state balanced budget mandates have been two major factors preventing the expansion of fiscal policy in the U.S. Rightly or wrongly, these issues have been put on the back burner by the presidential candidates, who have promised changes on the both taxation and spending policy to improve the U.S. economy.

John Canally is chief economic strategist for LPL Financial.