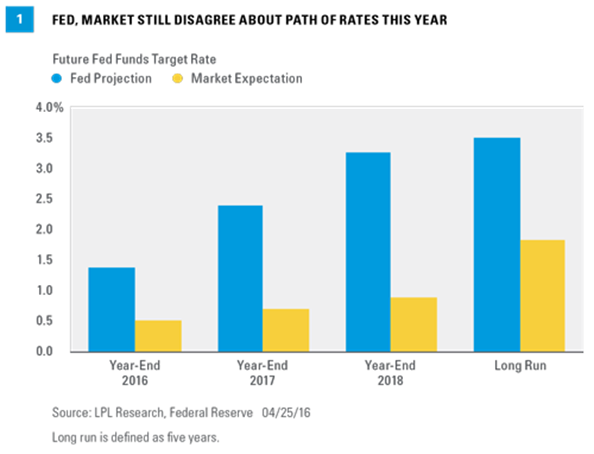

As the third of eight Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) meetings of 2016 approaches later this week, the market and the Federal Reserve (Fed) again remain deeply divided over the timing and pace of Fed rate hikes. The FOMC’s latest forecast of its own actions (March 2016) puts the fed funds rate at 0.875% by the end of 2016. As of April 25, 2016, the market (according to fed funds futures) puts the fed funds rate at around 0.60% by the end of 2016 [Figure 1], essentially pricing in just one more 25 basis point (0.25%) rate hike this year. How that gap closes—between what the market thinks the Fed will do and what the Fed is implying it will do—against the backdrop of what the Fed actually does will continue to be a key source of distraction for markets in 2016. Our view is that by the end of 2016, the fed funds rate will be pushed into the 0.75–1.0% range.

WHAT IS THE SCHEDULE OF EVENTS FOR THE FED THIS WEEK?

This week’s meeting will be followed by an FOMC statement at 2:00 p.m. ET on April 27, 2016, but Fed Janet Chair Yellen will not hold a press conference nor will the FOMC release a new set of economic forecasts for gross domestic product (GDP), the unemployment rate, and inflation, or fed funds projections (dot plots). The bad news is that the FOMC statement is the only way the FOMC will communicate its views on the U.S. and global economy and the expected path for the fed funds rate to investors this week. The good news is that financial markets are far less frazzled than they were in late January 2016, the last time the FOMC held a meeting without a press conference or new set of economic forecasts and dot plots.

HAS THE MARKET PRICED IN A RATE HIKE AT THIS WEEK’S MEETING?

In short, no. As of Monday, April 25, 2016, the fed funds futures market has priced in just a 2% chance of a 25 basis point rate hike at this week’s meeting. Another good proxy for what the market is pricing in is the yield on the 2-year Treasury note. Although the 2-year note yield has moved higher in the past two weeks (from 0.70% in early April to 0.82% as of April 25), it has moved lower since the last FOMC meeting (March 15–16, 2016), when the yield on the 2-year note stood at 1.0%. In addition, at 0.82%, the 2-year yield is below where it was (1.0%) when the Fed hiked rates in mid-December 2015 [Figure 2].

DOES THE FED CHANGE MONETARY POLICY IN AN ELECTION YEAR?

The short answer is yes, despite misconceptions the Fed stands down before major elections. While the Fed often pauses in the month or so prior to the November election, the Fed has changed policy (either raised or lowered rates or stopped or started quantitative easing [QE]) in every election year since at least 1968, and we don’t expect anything different in 2016.

WILL ELEVATED VOLATILITY IN THE MARKETS DETER THE FOMC FROM RAISING RATES?

As we noted in our prior FOMC meeting preview in mid-March 2016, the Fed as an institution and the individual members of the FOMC have a much higher threshold for financial market volatility than financial market participants, investors, and the financial media. There is no question that global financial markets have seen wild swings so far in 2016, with the S&P 500 falling 12% in the first few weeks of 2016, rallying by 7%, and retesting the lows of the year in mid-February 2016, before rallying 15% in the past month. Other markets (commodities, Treasuries, etc.) have seen similar swings.

Although the Fed clearly monitors activity in financial markets, it rarely, if ever, cites financial market weakness as a reason to change (or not change) monetary policy. The FOMC statement released this week is not likely to acknowledge the recent market volatility, but instead say it is continuing to monitor “global economic and financial developments,” as it noted in the FOMC statements released in both January and March of this year.

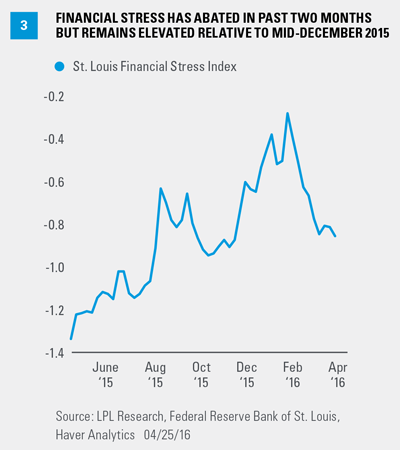

Instead, the Fed typically focuses on financial conditions. We note that Fed Chair Yellen referred to financial market conditions four separate times during her post-FOMC press conference in mid-March 2016, and another three times in a speech she made to the Economic Club of New York on March 29, 2016. The Fed tracks several measures of financial conditions, or financial stress. Figure 3 shows the St. Louis Fed’s measure of financial stress, where a reading above zero indicates above average financial stress. It aggregates stress levels in equity, credit, interbank lending, and the securitization markets in the U.S. and abroad. Over time, a rising level of financial stress indicates tightening financial conditions.

While financial stress has abated somewhat in the past two months after a sharp run higher in the first six weeks of 2016, the stress level remains above where it was just after the Fed raised rates in mid-December 2015. Said another way, the financial markets have done the Fed’s job of “tightening policy” and slowing the economy over

WHAT ABOUT INFLATION EXPECTATIONS?

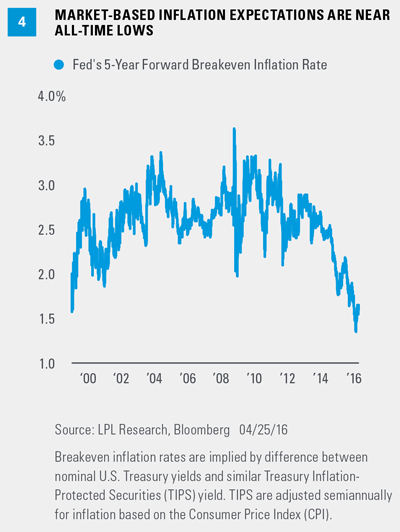

In her post-FOMC press conference in mid-March 2016, Fed Chair Yellen noted that “inflation expectations remain reasonably well anchored” and that “survey-based measures of longer-run inflation expectations are little changed, on balance, in recent months, although some remain near historically low levels. Market-based measures of inflation compensation also remain low.” The Fed tracks inflation expectations using both survey-based and market-based data. The University of Michigan’s survey of consumer expectations over the next 5 to 10 years has moved lower in recent months and is at the lower end of the 2.5–3.0% range it has been in for the past 18 years. Low inflation expectations beget low inflation, and the Fed doesn’t want to jeopardize this trend. Market-based inflation expectations (the difference between the yield on a 5-year Treasury note and a 5-year inflation-protected Treasury note, or TIP [Figure 4]) stands at 1.62% as of late last week, up from the 1.32% level—an all-time low—in mid-February 2016; but it is still below the 1.72% from mid-December 2015, when the Fed raised rates for the first time since 2006.

John Canally is chief economic strategist at LPL Financial.