Successfully preserving wealth across generations is not easy. Transferring values is even harder. Many wealth creators have suffered the heartbreak of seeing their money and family cohesiveness diluted after only one or two generations. Other families have created positive, enduring legacies that persist into the third, fourth and fifth generations.

What have the successful families done differently? In our experience, these families have prepared wealth for the next generations not only through thoughtful planning, but also through timely communication and education. For many families, a multigenerational family meeting offers a perfect opportunity to start this preparation.

Why Have A Family Meeting?

In our experience, gradually sharing a wealth plan with the next generation creates an atmosphere of trust, as family members welcome the transparency and reduced uncertainty a unified message offers. Additionally, when younger family members feel they are trusted, they are more likely to understand and respect the responsibilities that accompany an inheritance. If the wealth creator augments this trust with a solid financial education and communication of the family’s history and values, the next generation has a better chance of adopting a stewardship mind-set—a sense that the family shares something greater than financial assets.

A family meeting offers a safe, structured environment for communication and an opportunity to detail the family wealth plan, either in part or in full. Family meetings come in all shapes and sizes. Each is unique and dependent on the family’s objective. Meetings may be in-person or virtual, span an afternoon or a weekend, and include a single generation or multiple generations. In all cases, however, great care should be taken to prepare participants for the meeting. Everyone should be given the opportunity to weigh in on the agenda, and they should be told what to expect and what is expected of them.

When To Start

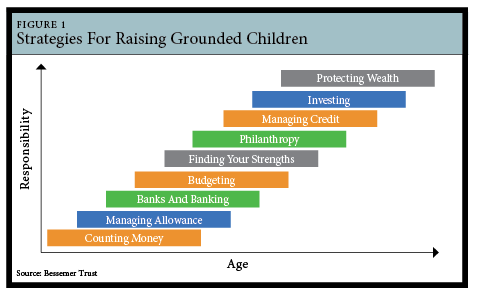

The timing of a family meeting depends on several factors, including participants’ ages and the meeting objectives. Ideally, family meetings start when the next generation members are in their teens and early 20s, and focus on providing a basic financial education. If members of the next generation are trust beneficiaries, we recommend starting this process well before any required disclosure date, typically at the age of 18. For these meetings, we suggest crafting age-appropriate lessons on personal finance and investments that layer in the family’s values and history. If the family owns a business, we typically encourage them to start formalizing their decision-making process—essentially creating a family governance structure—before the third generation is of working age.

However, families do not have to wait until the next generation members are teenagers. Many families benefit from regular meetings that begin when the children are younger. These family meetings may focus on the importance of developing savings plans from allowances or finding worthwhile charitable causes to support. These types of early meetings help children develop skills they will use to integrate family values with wealth stewardship plans (Figure

1). Teaching The Meaning Of Money

Rather than initiate family meetings to share a wealth plan, families may want to consider a more basic goal for their meeting: teaching children about money.

We’ve used an interactive exercise at Bessemer Trust called “Money Messages,” popular among younger clients, in which each person identifies the message he or she grew up with and the message he or she would like to live by. Sometimes the messages are the same, but most often they are different and reflect how far along the family is in integrating wealth into their lives. In these and other meetings, family members get to know each other on a slightly different level and learn how to work together. Interactive exercises also allow elders to observe the younger generations’ family dynamics and maturity levels in order to decide how much of their wealth plan to share and when to share it.

In one case, the grandparents elected to share two parts of the plan—funding the grandchildren’s educations and establishing a private foundation—so that it dovetailed with the discussion about what money could and could not do for the family.

Establishing The Ultimate Objective

A successful family meeting starts with a clear objective that participants understand and have consented to.

While there is often an individual or event that acts as the catalyst for the meeting, we recommend interviewing all participants in advance to collect information on potential hot-button issues or additional interests. A third party—often the meeting facilitator—typically will either conduct the interviews or gather feedback through an anonymous survey. The survey input helps inform other meeting aspects including design, participants, location and length. In fact, it is not uncommon for the interviews to help shift the objective of the meeting in a way that is more meaningful to all family members.

After the family establishes the primary meeting objective, our team works with them to refine it. For example, while clients might know that they wish to use a family meeting to share all or part of a wealth plan, they might have an ancillary objective, such as addressing a current family concern.

In one example, clients who were grandparents sought help to resolve a conflict over their adult children’s use of a vacation home. The clients were afraid that the family’s increased wealth and resources were causing family ties to unravel. In addition, they thought it was time to share their wealth plan with their children and grandchildren. To address their concerns and to allow for communication of their intentions, we suggested that they hold a family meeting.

Because we knew there was tension in the family, we asked permission to interview the participants in advance to better understand the crosscurrents at work. From there, we could create the most relevant agenda for the meeting. During our interviews, we realized that there was an elephant in the room that hadn’t been previously mentioned: Members of the second generation were grappling with the larger issue of their new wealth. They were struggling to raise their own children as grounded individuals and were judging their siblings’ spending and parenting habits harshly.

We then used these interviews to refine the meeting objectives to deal with the additional issues we uncovered. The clients decided that they wanted to encourage a sense of intellectual curiosity and shared learning among family members. Second, they wanted to foster a sense of stewardship and entrepreneurship in the future generations—especially among their grandchildren. Third, they wanted the money to be used to help keep the family together.

In this case, the family meeting was very successful. The carefully crafted agenda, in conjunction with our facilitation of the discussion the clients wanted, softened the sibling dynamics. They communicated with each other and admitted that they never wanted their own children to experience similar tensions. They also expressed their admiration and gratitude for their parents’ decision to use their family wealth to further the education and business ventures of the grandchildren. And, as the clients had hoped, the siblings developed a policy about how the vacation home would be used. They quickly solved the problem that sparked the need for the meeting. We attribute this positive outcome, in part, to our ability to refine the clients’ objectives and design an appropriate agenda.

Role Of The Facilitator

When the family has established a clear objective and the meeting agenda, an outside facilitator or co-facilitator may be helpful. A good facilitator will help ensure that everyone is engaged and contributes to the conversation, will keep track of timing and will assist in handling areas of potential conflict. We often find that younger generations have important insights to share, but may feel their opinions are secondary. A good facilitator will make sure that the younger generation contributes to the conversation. To establish an inclusive tone, some families start the meeting with an exercise to help identify the different communication styles in the room and review the principles behind active listening. Others develop a code of conduct to keep conversations constructive.

A code of conduct typically includes such items as:

• Be punctual and prepared.

• Don’t interrupt.

• Treat disagreement as an opportunity for learning.

• Address issues with the people involved before involving others.

• Honor the statute of limitations on all specific issues.

When we act as facilitator, we often introduce compelling, low-risk activities to spark fresh insights among family members and enhance communication from one generation to the next. For example, at one family meeting, we asked each person to say something admirable about the person seated on the right. A younger brother turned to his adult sister and told her he had admired her courage as she worked her way through a painful divorce. The brother’s important vote of confidence was surprising and touching—and might not have been shared unless prompted. As a family member said during a break, “These meetings are so important … because we change and we forget to tell each other.”

Donna TrammelL is managing director and director of family wealth stewardship at Bessemer Trust.