“This generation of Americans has a rendezvous with destiny.”

– Franklin D. Roosevelt

“Each generation imagines itself to be more intelligent that the one that went before it, and wiser than the one that comes after it.”

– George Orwell

After a lifetime of watching financial markets, the speed at which traders react still amazes me. Sometimes it seems to me like they hail from the “ready, shoot, aim,” school of thinking. Economic trends almost never turn on a dime; and though we can look back and find a moment that was the exact bottom or top, there were forces building that caused people to move from one side of the boat to the other, tilting the economy or markets or society in a different direction. New data can alter our probabilities – but rarely as fast as trading algorithms seem to think. Long-term trends, by definition, change slowly.

I had that thought in mind when I asked Neil Howe to be our kick-off speaker at the Strategic Investment Conference and invited Niall Ferguson to wrap it all up three days later. As historians, they both gaze back through time to identify patterns and draw lessons. They were the bookends who framed the wide-ranging discussions in between. They have both been very influential in helping me develop my understanding of the world.

As I said two weeks ago, the experts I brought to the conference, even the ones I expected to be raging bulls, were mostly bearish. The surprise was Niall Ferguson, who has become the new raging bull. That’s pretty much the one thing you can count on at my conference: surprises! But you can see that even Niall is deeply concerned about much of what is happening in the world.

Now, as I reflect, I see how the various crisis forecasts fit Neil Howe’s “Fourth Turning” formula. Today I’ll tell you why. I’m going to do something a little different in this letter in that I’m going to borrow wholesale from Neil’s speech at the conference and his voluminous writings in order to give us a view of what to expect in the next five to eight years. And given that the Brexit vote looms next week and that it’s part and parcel of what Neil is talking about, I will offer some final thoughts on Brexit. That should be enough to keep us occupied for the next few minutes.

Before we dive in, let me note that I realize this letter is very US-focused. That said, the concept of generations and turnings is not just a US or Anglo-Saxon phenomenon. All nations, all peoples, experience their own recurring cultural seasons and changes. No part of humanity is exempt from this process. Some of my best late-night conversations with Neil have been about the generations and turnings of different countries (especially China). Sometimes, at the end of the evening, I wish that I had secretly recorded our conversation so I could have it transcribed and review it later. Alas, I’ve never had the foresight to do so.

The Fourth Turning

I think the framework of “generational change,” and specifically the concept of the Fourth Turning, originally appeared in a 1997 book by that name, written by Neil Howe and William Strauss (who, very sadly, died a few years ago from pancreatic cancer – a great loss) are very important in understanding what is happening in our society. The concepts don’t attempt to explain the current turmoil in its entirety, but they do enable us to frame our thinking about our time in context, in the stream of history.

It is one of the great ironies of life that each generation believes its experiences are unique. This is not unlike teenagers thinking that their parents can’t possibly understand the emotions pouring through them, certain that the old fuddy-duddies could never have experienced such emotions themselves. The reality is that we have seen this movie before – with different actors and main characters and plot twists and technological devices, to be sure – but the basic plot seems to push along a hauntingly familiar path.

I have to warn you: some of what follows won’t be encouraging because, as Neil says, we’re in a Fourth Turning. Fourth Turnings are crisis periods, and we are barely halfway through this one. But take heart: better times await us on the other side of the crisis.

Neil has a research service that looks at how generations affect markets and economics and products and companies. I find their work fascinating. The service is not cheap, but if you are running a major fund or are responsible for choosing specific investments, I think you will be richly rewarded with ideas and insights for your dollar. You can learn more about Neil’s firm at www.saeculumresearch.com. You can also see six free videos of interviews of Neil discussing a wide variety of subjects, at Hedgeye.com.

And now I will try to take my notes from Neil’s speech and my familiarity with his writings and distill the essence of his lessons. This letter will not substitute, though, for your actually buying The Fourth Turning and reading it; and those who want further understanding can go back and read Strauss and Howe’s previous book, Generations: The History of America's Future, 1584–2069.

Attitudes Are Generational

Every parent who has watched children grow into adults knows that our personalities form early in life. Psychologists from Sigmund Freud forward have generally agreed: our core attitudes about life are largely locked in by age five or so. Changing those attitudes requires intense effort.

Howe and Strauss took this obvious truth and drew an obvious conclusion: if our attitudes form in early childhood, then the point in history at which we live our childhood must play a large part in shaping our attitudes.

Howe and Strauss added a corollary: it’s not just early childhood that forms us. We go through a second formative period in early adulthood. The challenges we face as we become independent adults help determine our approach to life.

These insights mean we can divide the population into generational cohorts, each spanning roughly twenty years. Each generation, then, consists of the people who were born and came of age at the same point in history. They had similar experiences and thus gravitated toward similar attitudes.

Members of each generation are also individuals, of course. Family and other circumstances leave each person more or less attached to the broader attitudes of their time. Generational attitudes don’t determine everything, but they’re still important.

At SIC, Neil illustrated the point with this cartoon. (I think we should now add an illustration of a couple texting on their phones, saying “Let’s tell our friends online first.”)

Amusing, yes, but true. Young love, a universal experience, took different forms for Americans who grew up in the 1950s vs. the 1970s vs. the 1990s. Ditto for many other aspects of life.

Until recently it was unusual to have more than four generations alive at the same time. Improved longevity means we now have six generations among us.

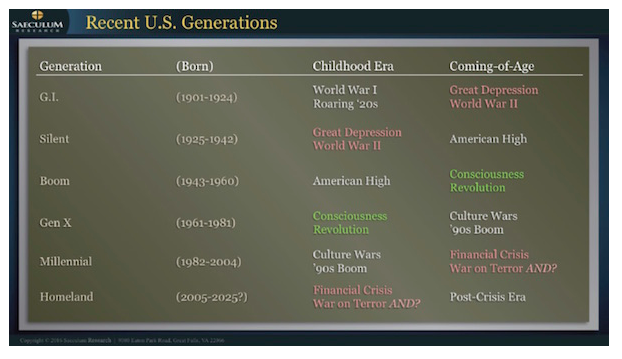

Our oldest citizens are from the “G.I. Generation,” or what Tom Brokaw famously called the “Greatest Generation.” Born from 1901–1924, their childhood milieu included World War I and the prosperous Roaring ’20s. As young adults, they experienced – and eventually overcame – the challenges of the Great Depression and World War II.

The Silent Generation, born 1925–1942, watched as children while their parents met head-on the great economic and military challenges of that day. With the exception of a few, they were too young to participate directly in the war and entered adulthood in a time of post-war peace and prosperity. Howe calls that period the “American High.”

Those two generations have now either passed away or are well into retirement. They control a great deal of wealth, which gives them influence, but they no longer wield the levers of power. That role now belongs to the Baby Boomers (born 1943–1960) and increasingly to Generation X (born 1961–1981).

Next in line are the much-discussed Millennials (born 1982–2004) and then today’s young children, whom Howe dubs the Homeland Generation (born 2005–2025?). The social and economic influence of these latter two generations is growing as that of the Boomers and Generation Xers declines.

Heroes, Artists, Prophets, & Nomads

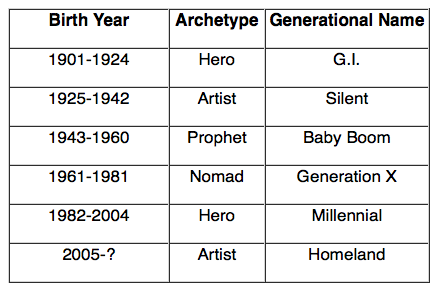

In their unbelievably prescient and prophetic 1997 book, The Fourth Turning, Howe and Strauss identified four generational archetypes: Hero, Artist, Prophet, and Nomad. Each consists of people born in a roughly twenty-year period. As each archetypal generation reaches the end of its 80-year lifespan, it is replaced by a new generation of the same archetype.

Each archetypal generation proceeds through the normal phases of life: childhood, young adulthood, mature adulthood, and old age. Each tends to dominate society during middle age (40–60 years old), then begins dying off as the next generation takes the helm.

The change of control from one generation to the next is called a “turning” in the Strauss/Howe scheme. The turnings have their own characteristics, which I’ll describe shortly. First, let’s look at the archetypes and how they match the generations alive today.

The characteristics of each archetype aren’t neatly divided by the calendar; they are better seen as evolving along a continuum. (This is a very important point. It is why we get trends and changes, not abrupt turnarounds. Thankfully.) People born toward the beginning or end of a generation share some aspects of the previous or following one. Obviously, individual differences can also outweigh generational identity for any particular person. (We all know people who were seemingly born in the wrong era.) The archetypes simply describe broad tendencies that, at the larger societal level, add up to significant differences.

Hero generations are usually raised by protective parents. Heroes come of age during a time of great crisis. Howe calls them heroes because they resolve that crisis, an accomplishment that then defines the rest of their lives. Following the crisis, the Heroes become institutionally powerful in midlife and remain focused on meeting great challenges. In old age they tend to have a spiritual awakening as they watch younger generations work through cultural upheaval.

The G.I. Generation that fought World War II is the most recent example of the Hero archetype. They built the US into an economic powerhouse in the postwar years and then confronted youthful rebellion in the 1960s. Further back, the generation of Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, heroes of the American Revolution, experienced the religious “Great Awakening” in their twilight years.

Artists are the children of heroes, born before and during the crisis but not old enough to be an active part of the solution. Highly protected during childhood, Artists are risk-averse young adults in the post-crisis years. They see conformity as the best path to success. They develop and refine the innovations forged in the crisis. Artists experience the same cultural awakening as Heroes, but from the perspective of mid-adulthood.

Today’s older retirees are mostly artists, part of the “Silent Generation” that may remember World War II but was too young to participate. They married early and moved into gleaming new 1950s suburbs. The Silent Generation went through its own midlife crisis in the 1970s and 1980s before entering a historically affluent, active, gated-community retirement.

Prophet generations experience childhood in a period of post-crisis affluence. Having not seen a real crisis, they often create cultural upheaval during their young adult years. In mid-life they become moralistic, values-obsessed leaders and parents. As they enter old age, prophets lay the groundwork for the next crisis.

The postwar Baby Boomers are the latest Prophet generation. They grew up in generally comfortable times with the US at the height of its global power. They expanded their consciousness when they came of age in the “Awakening” period of the 1960s, defined the 1970s/1980s “yuppie” lifestyle, and are now entering old age, having shaped the culture by virtue of sheer numbers.

Nomads are the fourth and final archetype. They are children during the “Awakening” periods of cultural chaos. Unlike the overly indulged and protected Prophets, Nomads go through childhood with minimal supervision and guidance. They learn early in life not to trust society’s basic institutions. They come of age as individualistic pragmatists.

The most recent Nomads are Generation X, born in the 1960s and 1970s. Their earliest memories are of faraway war, urban protests, no-fault divorce, and broken homes. Now entering mid-life, Generation X is trying to give its own children a better experience. They find success elusive because they distrust large institutions and have no strong connections to public life. They prefer to stay out of the spotlight and trust only themselves. Their story is still unfolding today.