The facts are simple — the birth rate is dropping everywhere, work-force growth is dramatically slowing (to negative in many countries), the median age is rising and people are living longer. The repercussions are immense. Pension and social security systems are inadequate, health care and retirement facilities ditto and government budgetary forecasts are not worth the paper they are written on due to slowing GDP growth.

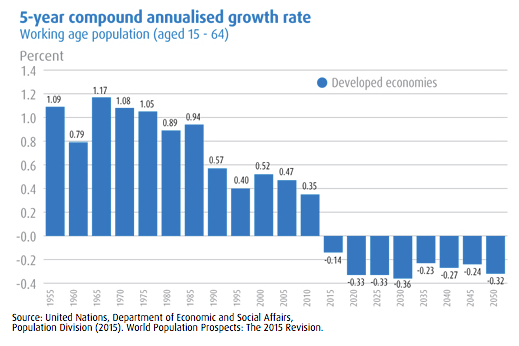

Economic growth is made up of the expansion in output per employed person (productivity) and the rate of growth of employed people. If the latter is steadily in decline then the potential rate of economic growth declines. And that is the pickle in which the world finds itself.

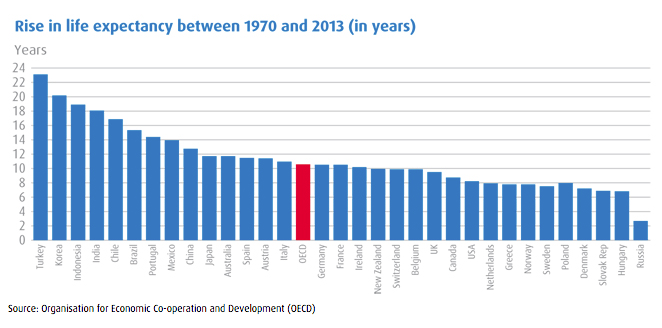

Pictures are better than words. Take a look at what has happened to average life expectancy in the relatively short period from 1970 to 2013.

It is remarkable that in many advanced economies, where life expectancy was already relatively high, it has increased by around 10 years over the period illustrated. In developing economies the increase tends to be higher. Whilst we should applaud the improvements in health care, diet and lifestyle that have permitted this trend to longevity we need to recognise that back in the 1970s this was not anticipated and not embraced in forward planning. Governments and others have been playing a game of catch-up ever since.

In 1950 the world’s average life expectancy was 46.8. Today, it is 70.5. The world’s median age was 23.5 in 1950, 22.5 in 1980 and 29.6 in 2015. In the advanced countries the median age has risen from 28.5 in 1950, to 31.9 in 1980 and 41.2 in 2015. Almost inevitably, Japan tops the median age list at 46.5, hotly followed by Germany at 46.2 and Italy at 45.9 (UN data).

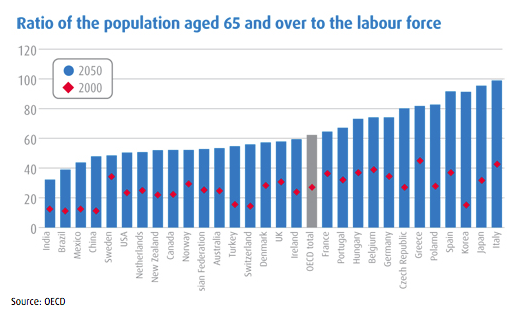

The countries at the far right of the chart have a real problem — the “oldies” (over 65) will be almost as numerous as the workers by 2050. The red dot shows the situation in 2000 and highlights the rapid deterioration in all countries over the period. And the working-age population? This is defined by the UN as all people aged between 16 and 64. In the developed world this segment of the population, on average, is now starting to shrink. This will deduct around 0.3% annualised from GDP growth over the next 35 years. In the previous 35 years it added an average of 0.4% annualised to developed world GDP growth. The combination of the two means a comparative (negative) growth differential of 0.7% annualised in the next several decades.

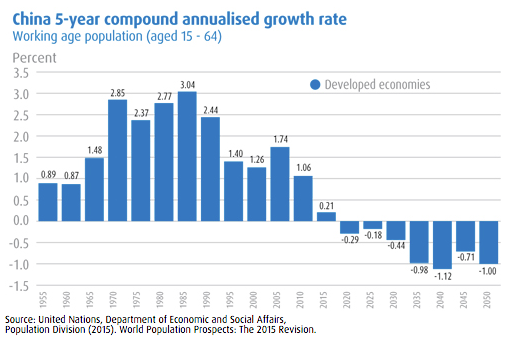

The boom country of the past twenty years, China, is about to experience a very dramatic change in fortunes due to its one-child per family policy — a policy that the government is only now getting around to amending — but it is very much a case of too little too late. Even if all the fetters are removed there is no indication that there will be a birth-boom in China. The potential working-age population starts to shrink about now providing a stark contrast to the growth of the past 50 years. A glance at the chart is sufficient to indicate that the comparative negative growth differential is going to be considerably more than 1% annualised.

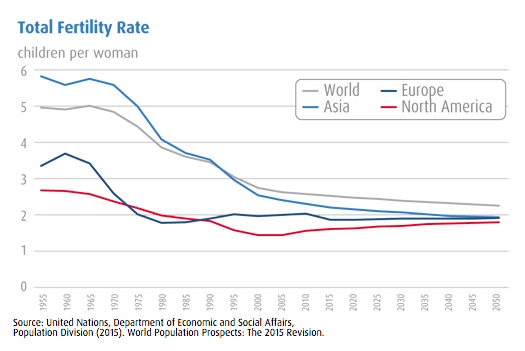

The fertility rate (children per woman) needs to be 2.1 for a population to maintain itself. Anything lower and shrinkage occurs. In all of the world’s regions the fall in the fertility rate has been nothing short of dramatic. Europe is in the most parlous position with the fertility rate now comfortably below replacement level.

So the picture that emerges is very clear — a rapidly ageing global population with steadily fewer workers (relative to the retirees) to maintain overall living standards. From an investment perspective behavioural economics now becomes a very important study. A legion of retirees behaves quite differently than an equivalent legion of younger workers. Retirees need income and security, spend a significant amount on healthcare, tend to be downsizing housing rather than upsizing, will not be seeking mortgages, are unlikely to be patronizing shops selling the latest fashions and will be liable to spend some of the kid’s inheritance on the odd cruise (the fastest growing holiday segment).

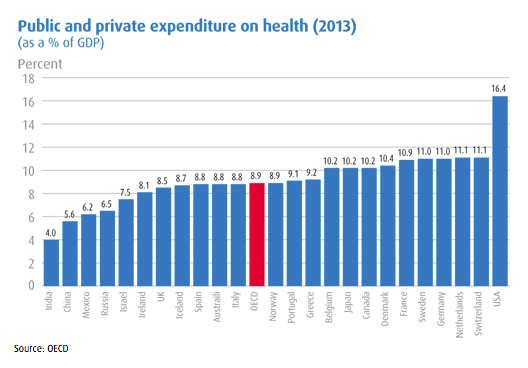

Healthcare is already a sizeable slab of the budget of most countries but it is about to get much bigger. No country rivals the “spend” of the U.S. (relative to GDP) but all will be rising up the scale over the next few decades. If more of the pie is spent on healthcare something else misses out. This is a substantial challenge for governments throughout the world — again, one that tends to be under-appreciated.

The impression may be gained from the preceding that there is no or at best little light at the end of the tunnel. Not so, as some countries are still experiencing booming population growth. We refer to countries such as India, Nigeria, Ethiopia, Pakistan, Tanzania and the Democratic Republic of the Congo which, between them, will total almost 3 billion people in 2050 according to the UN. The lion’s share of this is India which will expand from a current 1.3 billion to 1.7 billion, making it easily the most populous country in the world by 2050. China’s population is expected to fall by around 30 million over the same period but by a total of 370 million by the end of the century.

India’s working-age population will grow by 1.1% annualised over the next 20 years and an average of 0.8% annualised over the 35 years to 2050. The task is to make effective use of this growth-dividend.

The same comment applies to Africa, the continent where the bulk of the remaining growth occurs. We try not to be sceptics but we are only too aware that India and Africa have so often disappointed in the past. But the fact is that the world will need the people of working-age to be productively employed because elsewhere there will be a vast number of retirees sitting back hoping that someone is out there generating the wealth to fund their pension or social security benefit. Or perhaps it will be robots. Now there’s a topic for a future Global Investment Insights!

Bruce Campbell is founder and former CEO and chief investment officer of Pyrford International, part of BMO Global Asset Management.