A little while ago, Kevin Drum of Mother Jones -- a very smart and perceptive writer on economic and policy issues -- posed a big question: Why is finance so dominant in the U.S. economy?

How did this happen? Finance isn't a monopoly. In fact, it's one of the most globalized, fluid, and competitive industries on the planet. Why haven't its profits long since been reduced to zero, or close to it? I can understand occasional blips as markets change—CDOs and SIVs get hot for a while, so experts in CDOs and SIVs make a killing—but the overall industry? How has it managed to hold onto such outlandish rents for such a sustained period?

I think we do know a partial answer -- or several partial answers -- to this question.

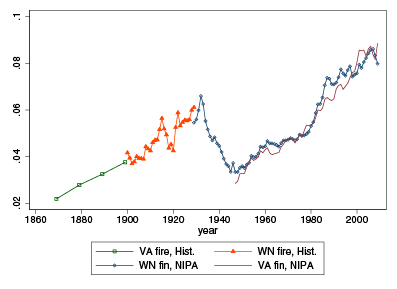

First, it’s important to point out that when an industry grows as a share of U.S. gross domestic product, it doesn’t always mean that it’s more profitable than before. Profitability could potentially shrink as an industry grows. But in the case of finance, that’s not what’s happened. Here, courtesy of economist Thomas Philippon, is a graph that shows finance’s share of GDP on the vertical y-axis:

As you can see, finance’s slice of the overall economy peaked at more 8 percent in the 2000s.

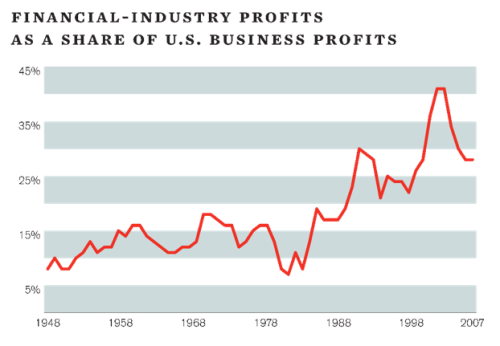

And here, via University of Connecticut law professor James Kwak, is its share of corporate profits:

One thing we see from these charts is that finance has always been a very profitable industry. In the '60s, when finance was less than 5 percent of the economy, it made 10 percent to 15 percent of the profits, even though it was more tightly regulated than now. That means part of the answer to Drum’s question -- the source of finance’s excess profitability -- might lie in the nature of the industry itself, or how we measure it, rather than in recent events.

But that can only be part of the answer. There are also two other questions. First, why did finance grow so much as a percent of output since 1980? And second, how did it keep being so profitable even as its size ballooned?

Let’s start with the question of why finance has grown so much in recent years. We can get some clues to this by considering which parts of finance have grown. Financial economists Robin Greenwood and David Scharfstein took a look at this back in 2013, and found that the acceleration since 1980 has come from two sources: 1) asset-management fees, and 2) lending to households.

Asset-management fees are middleman costs that all kinds of players in the finance industry charge to move money around. These fees are usually charged as percentages of the assets being managed. The amount of wealth in the U.S. economy has soared since 1980 -- just think of the rises in the housing and stock markets over that time -- meaning that the middlemen in the finance industry have been taking their percentage fees out of a much larger pool of assets. That has increased finance’s share of national income. People also started to put more of their money in asset markets -- where money managers charge percentage fees -- instead of keeping it in banks or government bonds, which don’t.

But why have profits from these middleman fees stayed so high? Why haven’t asset-management charges gone down amid competition? In a recent post, I suggested one answer: people might just be ignoring them. Percentage fees sound tiny -- 1 percent or 2 percent a year. But because that slice is taken off every year, it adds up to truly astronomical amounts. So if people are just ignoring what middlemen skim off the top, because each fee seems small, investors could be handing significant fractions of the country's GDP to the financial sector out of sheer carelessness. That would certainly keep profits high; if many investors pay no attention to what they're being charged, more competition can’t push down those fees.

So a combination of rising asset values and unchanging management fees can explain a large part of both finance’s growth and its continued profitability.

The other big piece of finance’s growth has been household credit, with a lot of it going for big ticket items like houses and cars, U.S. households have been borrowing more and more since 1980 -- as Greenwood and Scharfstein report, household credit soared from 48 percent of GDP in 1980 to 99 percent in 2007. Mortgages were by far the biggest piece of this. When people borrow more, the finance industry makes money by collecting interest, and also by charging middleman fees on lending transactions.

Why did people borrow so much more? One big reason was the growth of securitization, which allowed the finance industry to convince itself that it was lending money safely to people it never would have extended credit to before. That, of course, had disastrous consequences in 2008, but securitization remains a big part of the lending industry. Also, Greenwood and Scharfstein suggest that people might have just decided to borrow more -- homeownership and/or house flipping might simply have gotten more popular, allowing the finance industry to reap a gigantic windfall.

But that leaves the question of why lending remained profitable. Why didn’t new lenders enter the market and push interest rates and middleman fees down? Well, rates certainly fell, but not enough to cancel out the growth in the industry’s size. One possibility is that lending has significant economies of scale -- that big banks will always be able to lend money more cheaply, at higher volumes, than small ones. That would tend to preserve profit margins as the size of the lending increased.

So I would say that we have a partial answer to Drum’s big question. The finance industry grew in size because U.S. asset markets rose in value, and people borrowed more. As to why the finance industry retained its enormous profit margins -- or why it was so profitable even before 1980 -- this isn't as clear. Old explanations -- economies of scale and other barriers to entry -- are a possibility. Behavioral effects, like simple ignorance of middleman fees, are another. But the extreme profitability of finance is not yet well-understood. This is a puzzle for economists to work on.

Noah Smith is an assistant professor of finance at Stony Brook University and a freelance writer for a number of finance and business publications.