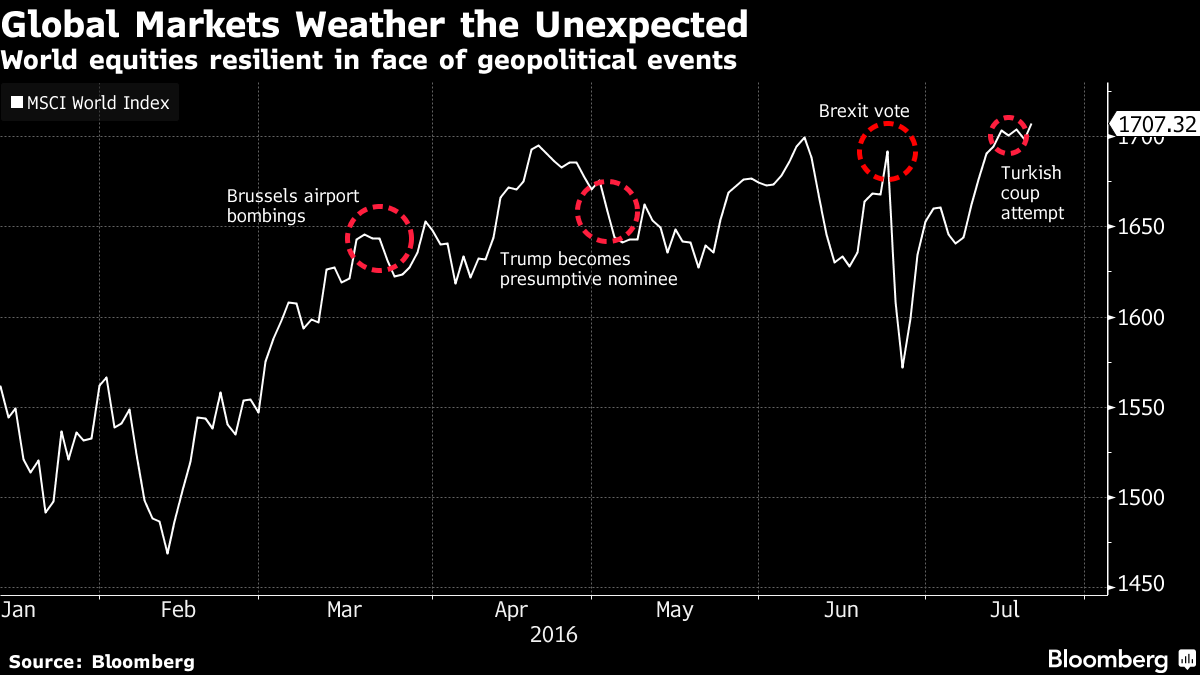

Say at the beginning of the year you knew how the British secession vote would turn out, and that Donald Trump would be nominated for U.S. president. Say you also foresaw an army uprising in Turkey, the fall of Brazil’s president and terrorism in Brussels and Nice.

Where would you have said markets would be on July 21? Would you have bet on the S&P 500 Index sitting at a record, global corporate bond yield premiums close to the narrowest in a year, or emerging-market currencies 8 percent above their January lows?

Such is the plight of forecasters, who have been mostly correct in their view that 2016 would be a year marked by rising political danger. The problem is, mostly correct has been pretty much wrong when it comes to calling markets, another example of the near impossibility of making accurate price predictions in a world dominated by central-bank stimulus, subzero bond yields and tepid economic growth.

“You probably would have done worse if you knew the outcomes ahead of time,” Bill Stone, chief investment strategist at PNC Wealth Management in Philadelphia, said by phone. “Recent events certainly illustrate the futility of trying to make investment decisions based on geopolitical outcomes.”

Monetary stimulus, ranging from interest-rate cuts to bond purchases that have swollen major central-bank balance sheets by $7.2 trillion since 2009, has fueled risky assets since the financial crisis while keeping economies afloat though mostly drifting. Policy makers have been as generous as ever in the aftermath of this year’s political dramas. The result has been markets made ever more mysterious when viewed through traditional investment models.

Take U.S. stocks, where valuations last week climbed above 20 times earnings for the first time in seven years. Profits aren’t rising, share buybacks and takeovers are calming down. And yet, with Brexit, the Nice attack and Turkey’s thwarted coup as backdrop, the S&P 500 has rallied for three straight weeks, closing at a record for the first time in 13 months. It slipped 0.1 percent to 2,171.05 at 9:33 a.m. in New York.

One reason for the rebound is the refusal of the U.S. economy to fall into a recession. Another is conditioning. Since the financial crisis, speculating on protracted declines simply hasn’t paid off, thanks in part to the willingness of central banks to stanch losses.

Limit Debated

“Part of the resilience is that policymakers are on the case, they’ve been aggressive in response to these shocks,” Ben Mandel, a global strategist with JPMorgan Asset Management’s multi-asset solutions team, said by phone. “There is a limit to it, ultimately.”

Bets on that limit haven’t panned out. In May, Morgan Stanley chief cross-asset strategist Andrew Sheets proposed an alternative to the “sell in May” investing adage, encouraging clients to buy positions that benefit from rising volatility. Around that time, Bank of America Corp. chief equity strategist Savita Subramanian predicted a “ vortex of negative headlines” in June could push stocks lower.