Seeking to mine gold from market inefficiencies, academics have spent decades trying to discern persistent patterns behind the statistical returns on different classes of equities. Advisors have watched them debate the merits of small-cap stocks vs. large-cap counterparts and value vs. growth.

But Roger Ibbotson, founder of the eponymous investment research and consulting firm and chairman and chief investment officer of Zebra Capital Management, has discovered another dimension to the performance analysis landscape: liquidity. Keynoting the first annual Innovative Alternative Investment Strategies conference in Chicago on July 28, Ibbotson discovered stunning return differentials with equities when they are classified according to their liquidity.

The results are published in a working paper, "Liquidity As An Investment Style," that Ibbotson co-authored with Zhiwu Chen in July 2007. It was updated in December 2009.

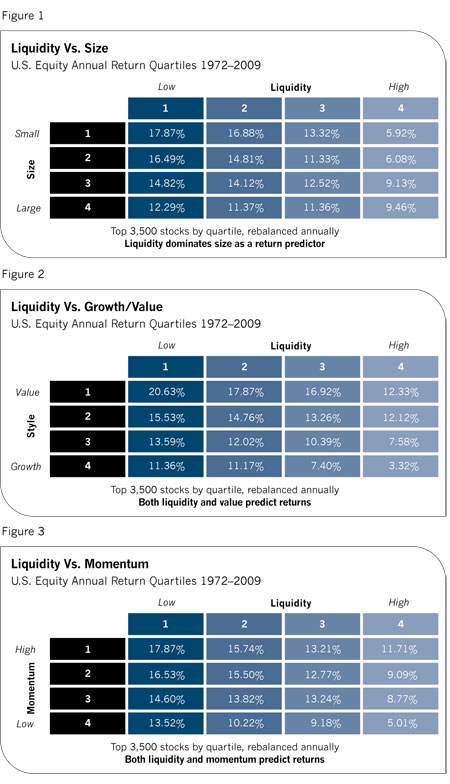

"Liquidity dominates size" as a return predictor, Ibbotson told attendees. "Public equity markets have gradations of liquidity with different liquidity premiums."

It should be noted Zebra Capital is launching several investment products based on the research. When one looks at the charts that accompany this article, it's easy to see why.

Ibbotson studied 3,500 U.S. stocks by quartile and rebalanced annually from 1972 to 2009. He defined liquidity as total annual trading volume divided by total shares outstanding. One takeaway from his presentation at the conference, which focused on alternative investments, was that investors don't have to go all the way down the liquidity spectrum to private equity to find additional return.

That's because Mr. Market apparently is willing to pay a higher price for the most liquid securities, reducing returns from these equities.

The notion of liquidity as an investment style makes intuitive sense. Everything else being equal, why wouldn't investors pay a higher price for the same set of cash flows if trading were cheaper and easier?

Ibbotson also turned that concept upside down. Keeping all other factors equal, why shouldn't investors pay a lower price for the same cash flows if trading costs more and requires them to expend more energy?

How much, Ibbotson asked the audience, should advisors pay for liquidity their clients don't need? Many big university endowments ran into serious problems with illiquid investments during the financial crisis, but Ibbotson confined his research in this study to public securities. And his working paper notes that the research would lead an advisor to select a portfolio biased toward more thinly traded equities that would still be relatively liquid.

Ibbotson's data produced some interesting findings. Take the small-cap universe, which is broadly presumed to generate higher returns that can be traced to a so-called size premium.

That's true for some small-cap shares, but when Ibbotson sorts smaller-company equities into different classes based on their size and liquidity over a 37-year period, some interesting facts emerge. The worst-performing group is highly liquid, small-cap stocks, which returned 5.9% annually over the period. Ibbotson's explanation is that these are micro-cap stocks that have been "pumped up."

In contrast, the equities that have produced the best returns over 37 years were illiquid small-cap concerns, which generated an astonishing 17.87% annual return over nearly four decades. In all likelihood, these companies represent small, overlooked companies that attract little interest or trading activity.

It should be noted that studies of the small-cap performance advantage-some of them based on Ibbotson's data-have found that most of that outperformance since 1926 can be traced to a nine-year period from 1974 to 1983. That era was characterized by gas station lines, stagflation and two nasty recessions, and yet small stocks levitated while blue-chip companies watched their shares founder.

While the trend persists among large-company stocks, the premium for illiquid big businesses is much narrower. The most liquid shares of large firms returned 9.46% while the least liquid among this group recorded a 12.29% annual gain over the 37-year period.

Taking a look at the liquidity of value and growth stocks, Ibbotson's research produces its most striking variances. While the findings support the French-Fama theory that unloved stocks offer a premium, the differentials are so wide they throw the whole efficient markets hypothesis into question.

Highly liquid growth stocks, the stocks everybody knows and many portfolio managers own, performed dismally, throwing off a meager return of 3.32% a year over almost four decades. In contrast, the least liquid value companies gave investors 20.63% annually during the same time frame.

Liquidity as a predictor of returns evens works when equities are sorted based on their momentum. However, Ibbotson offered several caveats in this area.

"Momentum has become far more erratic in recent years" as a return predictor, he explained. In the past, it used to exhibit more clairvoyance about where equities were headed.

The equities with the most liquidity and the least momentum performed poorly, producing an annual return of only 5.01% during the period. Those with the least liquidity and the most momentum performed best, generating a return of 17.87%.

While Ibbotson said his research into liquidity holds when it is extended to global investing, there have been periods when it didn't pan out. "This is not something that works every year, notably in 1999," when the tech bubble was approaching its zenith, he observed. However, it worked extremely well after that bubble burst in the 2000-2002 period.

"Liquidity is also mean-reverting," he told attendees, adding that there is some evidence that mutual funds biased in favor of illiquid stocks have higher returns. "Stocks move in and out of favor as liquidity rises or falls and as valuations rise or fall."

In some ways, Ibbotson likened liquidity as a style to private equity, commenting that it is most appropriate for investors seeking higher returns with longer time horizons.

What is so striking about Ibbotson's research is how consistent the return patterns are across different slices of the equity markets. Of course, research has shown that other patterns of performance-like equal-weighted indexes beating their market capitalization-weighted counterparts-work well for sustained periods of time. Until they don't.

Asked about his outlook for the next ten years, Ibbotson voiced concern about the fixed-income markets, which have performed extremely well for the last three decades. This is prompting too many investors to overallocate assets to bonds, wondering why they should invest in stocks if they can earn almost as much or more bonds. These folks could be headed for major disappointment.