Preface

1 S. Blinder (August 2015), “UK Public Opinion toward Immigration: Overall Attitudes and Level of Concern,” The Migration Observatory at the University of Oxford.

Jeremy Grantham co-founded GMO in 1977 and is a member of GMO’s Asset Allocation team, serving as the firm’s chief investment strategist.

I set myself a task this quarter to give my views on why suddenly so many strange things are going on in the US and in the UK and what they might mean. We in the US can see the turmoil resulting from the Brexit vote, which seems to have been undertaken almost casually, without the normal planning for consequences. It has been likened to a dog that to its amazement catches the car – now what? The consequences for the remarkable experiment of the European Union are unknowable but potentially profound.

The US political scene seems to me to have plenty of similarities and perhaps we, too, will have our “now what” moment before long.

The economic and financial background to these apparently uncontrolled political experiments is also novel and risky. In a way never seen before, our financial establishments are driving interest rates toward zero and beyond. How will this end? I think of these political, social, and financial experiments as Black Hole Experiments in which the further we push them, the more the laws of physics, finance, or politics begin to change in unknowable ways. We live in interesting times.

[On the investment front the equation remains the same: pushing stock prices higher are the twin forces of the Fed’s policy and corporate buybacks. Trying to push prices down is an impressive array of everything else: disappointing productivity, growth, and profit margins together with all our domestic and international political uncertainties. And now Brexit! It is a testimonial to the strength of those two bullish forces that they can steady the US market near its high, regardless, apparently, of what is thrown at it. I therefore remain, on the basis of those two remarkable pillars of support, for at least one more quarter where I have been for the last two years; despite brutal and widespread asset overpricing, there are still no signs of an equity bubble about to break, indeed cash reserves and other signs of bearishness are weirdly high. In my opinion, the economy still has some spare capacity to grow moderately for a while. All the great market declines of modern times – 1972, 2000, and 2007 – that went down at least 50% were preceded by great optimism as well as high prices. We can have an ordinary bear market of 10% or 20% but a serious decline still seems unlikely in my opinion. Now if we could just have a breakout rally to over 2300 on the S&P 500 and a bit of towel throwing by the bears, things could change. (2300 is our statistical definition of a bubble threshold.) But for now I believe the best bet is still that the US market will hang in or better, at least through the election. P.S.: Having admitted my error in commodities, I would like to clock in the seventh anniversary of my “7 Lean Years” prediction for the economy back in 2009. The speed of the recovery, and particularly productivity gains, has been very lean indeed.]

Immigration from outside Europe is the potentially

explosive problem and Brexit may be the fuse

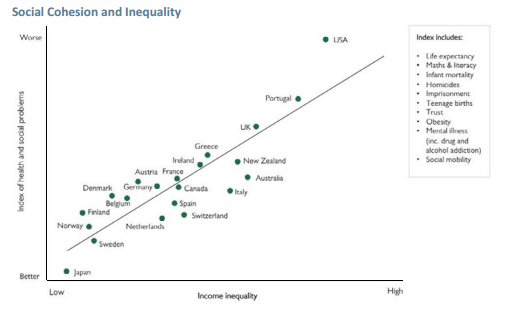

■ There is a consensus that social cohesion is the key to a successful society. It brings

with it the broadest range of advantages: greater economic mobility; longer lives and

better health; fewer babies born to teenagers; fewer traffic deaths, murders, suicides

and robberies; a smaller percentage in prison; and less stress and higher levels of

contentment, amongst others. Not bad.

■ The biggest simple input to social cohesion turns out to be income equality, which

is correlated highly with every individual measure of social cohesion listed above.

The exhibit below provides an example. Conversely, income inequality leaves the

impression, probably correctly, that the political voice of the poor has been lost or

weakened.

■ Gluttons for data on this issue must read The Spirit Level: Why Greater Equality

Makes Societies Stronger by Kate Pickett and Richard Wilkinson. It will make income

equalizers out of all of you.

■ According to the authors, both professors of sociology, Japan tops the list for both

income equality and social cohesion. It is closely followed in both by the Scandinavian

countries. At the other end, the US has deteriorated rapidly in both measures and now

ranks dead last among developed countries, with the UK not too far behind.

■ Economic growth, in fact, has been tilted sharply toward the better-off in both

countries. In the US, which for once is worse than the UK, there has notoriously been

no material progress since 1970 (45 years) in the real hourly wage, even as the income

of the top 1% has more than tripled. Tax rates have not attempted to balance this but

have actually changed to lower the relative burden on the well-off! Blue-collar work,

especially in manufacturing, has been hard to get in both countries. Since 2009 in the

US about 10 million new jobs have been created and a remarkable 99% have gone to

workers with at least some college education.

■ It might be expected that blue-collar and less well-educated workers would be

disappointed in both countries, and they are. Parents now widely believe for the first

time (ex the Great Depression) that their children will not be better off than they

themselves are. In these circumstances, social cohesion has rapidly decreased and

immigration has risen in importance, which we see in both the Trump campaign and

the pro-Brexit arguments.

■ Moving on to other data, when asked point blank in polls, “Do you think there are

already too many immigrants?” over 40% of the general public of most European

countries have answered “Yes” for decades.1 (The Scandinavian countries and Germany

were more favorably inclined in recent years.)

■ In the UK in the 1960s and 1970s, an admittedly difficult time for them, the “Yes”

vote ran around 80% with a high of 90% in 1974! In the 1980s and 1990s, with better

economic times, the “Yes” vote steadily declined. Ironically, in light of Brexit, by 2015

it measured its lowest at about 55%. But still 55%. If the issue of a referendum can be

tilted toward immigration, 55% is obviously still a dangerously high number.

■ Looking at the effect of immigration on social cohesion, one must deal with a lot

of obliqueness in academic work: most papers seem to be reluctant to appear antiimmigrant

or racist. Yet most conclude that trust is usually lower in diverse groups

than homogeneous groups: that religious and visible differences – dress and skin

color – are less easily dealt with, not surprisingly, than immigrant groups with similar

cultures. My interpretation of various carefully stated conclusions is that when times

are good immigrant flows are perceived as a moderate and manageable stress to social

cohesion. This is true even among groups that are not happy with the general principle

of steadily increasing immigration.

■ When times are seen as bad, though, especially when jobs are scarce as they are for

blue-collar workers now, new immigrants are seen as far more problematic. When

combined with steady increases in income inequality (as they are in both the UK and

the US), weakened social cohesion, and high levels of dissatisfaction, immigration

issues become very significant.

■ At times, this response appears to ignore the actual economic facts. The “Leave” vote

in Brexit was uncorrelated with actual local wage gains over recent years, for example.

Some towns with excellent recent wage increases still voted “Leave” and vice versa.

■ With considerable (and understandable) ignorance of economic details, the Brexit

voters were expressing commonly held views that were often based on skewed data

and were also very easily manipulated by politicians and the press – which in the UK

often has editorial bias in all reporting. For Americans, think Fox News.

■ The UK voters’ knowledge of the salient facts did not look impressive in Brexit.

According to the number of Google hits, many were not too sure what the EU actually

is, let alone the precise implications of leaving it. There was considerable confusion

between Syrian refugees and intra-EU migrants. Above all, there was a strong

expectation that free trade with the EU could be retained without both payments to

the EU and free intra-EU immigration continuing (the conditions Norway agrees to).

There is absolutely no hope of that. If the UK really means to have its own immigration

policy, it will have to negotiate new treaties with the EU and the rest of the world,

and it will need to do so without experienced trade negotiators, who have not been

required in the UK for many years.

■ In that eventuality – no EU free trade agreement – many firms will slowly or quickly

move some of their business out of the UK and into the EU to avoid tariffs. London’s

financial business will be especially vulnerable.

■ With most voters substantially ignorant and many deliberately misled, there may

be an interesting consequence: extreme and rather rapid regret. As business and

consumer confidence quickly weakens, economic activity falls, and racist incidents

jump (at least 60% recently), there could be and should be disillusionment at the many

misrepresentations and apparent complete lack of preparedness and willingness to

actually lead by Brexit advocates.

■ The lack of clear constitutional rules around referenda in the UK and the uniqueness

in the EU of a country’s withdrawal provide waffle room. There can be plenty of time

before an irrevocable decision is made, and much can happen. Both Denmark and

Ireland reconsidered EU votes. My semi-educated guess is that there is a substantial

one in three shot that the UK will also reconsider.

■ If Brexit holds, pretty clearly Scotland will leave the UK as might Northern Ireland.

This will make a painful irony out of the single most frequently quoted reason for

leaving: “Make Britain British Again.” They will probably have to settle for “Make

England (and Wales) English (and Welsh) Again.”

■ In total, if Brexit occurs, the UK economy will be hurt for several years. In the longer

term, though, there may be some offset for the UK economy by virtue of having a

smaller financial sector and a more balanced, less London-centric economy.

■ Brexit may even stimulate the EU to reconsider its many weaknesses. It is

a particularly complicated exercise in government and as such is prone to

unfortunate decisions. It is less democratic than it needs to be, but it appears

to be much less democratic than it really is. It has been overconfident about its

acceptability to the general public of its member states and badly needs better

P.R. Brexit may be seen in 20 years as having woken up and revitalized the EU.

■ On the other hand, and perhaps more likely, Brexit may cause the failure of a noble

experiment that above all has brought peace to Europe. Germany just experienced

70 years of peace for the first time in its entire history. Adding to the long list of EU

deficiencies, Brexit may be the straw (or bale of straws) that breaks the camel’s back.

■ The key issues here are risk and unintended consequences. When you are muddling

through okay, as was the UK, with no wars or other complete disasters, why rock the boat?

■ The precautionary principle should apply. The unknowable, unintended pain from

Brexit for the UK, the EU (especially some of its more vulnerable members), and,

perhaps, the world are simply not worth the risk. By far the worst risk, and one

that is most underestimated to a weakened or collapsed EU in my opinion, is from

immigration or refugees from outside Europe.

■ The truth about immigration to the EU, in my view, is bitter. As covered in earlier

quarterlies, I believe Africa and parts of the Near East are beginning to fail as

civilized states.

■ They are failing under the pressure of populations that have multiplied by 5 to 10

times since I was born; climate for growing food that is deteriorating at an accelerating

rate; degraded soils; insufficient unpolluted water; bad governance; and lack of

infrastructure. Country after country is tilting into rolling failure.

■ This is producing in these failing states increasing numbers of desperate people, mainly

young men, willing to risk money and their lives to attempt an entry into the EU.

■ For the best example of the non-compute intractability of this problem, consider

Nigeria. It had 21 million people when I was born and now has 187 million. In a

recent poll, 40% of Nigerians (75 million) said they would like to emigrate, mostly to

the UK (population 64 million). Difficult. But the official UN estimate for Nigeria’s

population in 2100 is over 800 million! (They still have a fertility rate of six children

per woman.) Without discussing the likelihood of ever reaching 800 million, I suspect

you will understand the problem at hand. Impossible.

■ I wrote two years ago that this immigration pressure would stress Europe and that the

first victim would be Western Europe’s liberal traditions. Well, this is happening in

real time as they say, far faster than I expected. It will only get worse as hundreds of

thousands of refugees become millions.

■ The EU and Europe may support a few years of increasing numbers of these failing state

refugees, but that is all. They will fairly quickly have to refuse to take even legitimately

distressed refugees. The alternative – to take all comers – would likely be not just

a failed EU, but a failing Europe. The key question now is what social and political

problems will be caused by the stress of getting from here to there: from today’s chaos

to a time when European borders will have uniform and controlled immigration.

■ Brexit is an early warning of how sensitive this issue will be. A serious country, or at least

a formerly serious country, the UK is risking a lot at a small whiff of the immigration

problem that is coming. (Immigration problems in the US are trivial in comparison to

what Europe faces, yet they have already become a serious political issue.)

■ The EU (with or without the UK), and indeed the whole of Europe, must get a uniform

policy on immigration as soon as possible. Yet, based on what they say, they do not yet

appreciate the long-term seriousness of their predicament. They are, though, behaving

like headless chickens faced with the problems they already have. Problems that will,

when viewed from the future, appear to have been just moderate in scale.

■ By far the biggest downside of Brexit is that it serves to weaken the EU at exactly

the wrong time – as external immigration begins to seriously stress governance and

political cohesion.

■ In the larger context of immigration, because I believe I have no serious career risk

on this issue (touch wood!), I should say that I believe that the UK and many other

European countries have not had a net benefit from immigration. In 1945 they were,

in most cases, culturally and ethnically homogeneous. This was absolutely not the

melting pot situation of North America. Steady immigration was supported by the

elite-intellectual, political and economic. It occurred largely against the will of the

people in that more were nervous about increased immigration than were enthusiastic.

It seems likely that in most cases immigration made social cohesion more difficult.

■ Any offsetting economic advantage for the UK has to be on a productivity basis, for

driving GDP forward by population increases alone is no bargain in a small, overcrowded

island that feeds barely half its own population (although business support for growth

of any kind is often forthcoming). Possible productivity gains from immigration seem

at best to be insufficient to offset increased social stresses. There, I said it.

■ This does not mean that a country based on immigration (trained, if you will) cannot

integrate not just immigrants, but the whole idea of immigration. If times are good,

or good enough, for a sustained period and income inequality is held in some check

and social welfare is fine, you could end up like Toronto, everyone’s heroine in this

respect. If not, you could even easily end up with a melting pot history and the current

conflicted attitudes to immigration that we have in the US.

■ In case you missed it, my sympathies are split between admiration for Toronto and

sympathy for the voters of Doncaster, my hometown and a former coal mining center.

Its population has made moderate economic progress since 1945 despite the loss of

mining and other industrial activities, like most northern towns. But in looking at the

more important relative progress, inhabitants cannot avoid seeing how obviously the

fortunes of London bankers, the top 10%, and, indeed, the south in general have left

them in the coal dust. (Poetic license given Thatcher closed most of the mines and the

very last one closed recently.) They voted over two to one for Brexit.

■ On the margin, the Brexit vote was won because some key groups expected to lean

Brexit produced unexpectedly high margins: medium and small northern towns (such

as Doncaster), the elderly, and the less well-educated.

Codicil: the real blame for Brexit

■ The lack of serious political intent to narrow growing income inequality. This has

caused a growing disgruntlement of the bottom half of the economic order and the

usual weakening of social cohesion.

■ A lack of success in mitigating economic weakness in the formerly industrial north. As

globalization took their jobs, an epic effort was required to retrain and re-employ these

workers. Little was done. Northerners never much cared for London government and

Southerners in general at the best of times. Now feeling mistreated, with justification,

they took delight in making a rude gesture to the establishment.

■ Calling for an utterly unnecessary referendum by the Prime Minister for superficial

and short-term political gain. He could have muddled through anyway. Referenda

are dangerous. They allow for the true will of the people to be voiced, informed or

ill-informed, manipulated or not. Dangerous. As Churchill said (now much quoted),

“The best argument against democracy is a five-minute conversation with the average

voter.” He might also have commented about the willful laziness of the one-third who

never vote.

■ The UK press, the most egregiously editorialized in the developed world. The broad

circulation papers goaded and badgered their readers toward Brexit.

■ As for the politicians, forget it. Whimsical theories, back-stabbing disloyalties, a glaring

lack of planning and foresight. Above all, completely ignoring the precautionary

principle, playing with fire like children. Now those Brexiters that haven’t run away

can reap what they have sown, as unfortunately will the whole UK. If you will, the

pack of dogs can now try to work out what to do with that darned car.

Immigration And Brexit

July 19, 2016

« Previous Article

| Next Article »

Login in order to post a comment