So what happens next?

Following Prime Minister David Cameron’s decision to resign, The Conservative Party is now facing a leadership contest. David Cameron’s successor is likely to be announced at the party conference during the first week of October.

Whoever his successor is, she or he will have the unprecedented task of invoking Article 50 of the Lisbon Treaty, the formal mechanism by which a Member State may Leave the European Union (EU).

David Cameron has said that he and his Cabinet will remain in office for the next few months to “steady the ship.” George Osborne will therefore be staying on as Chancellor for the time being but will presumably not be enacting the "Brexit1 Budget" he outlined during the campaign. Any admission that the fiscal rules will be missed as a result of "extenuating circumstances" will therefore be one for the next Chancellor.

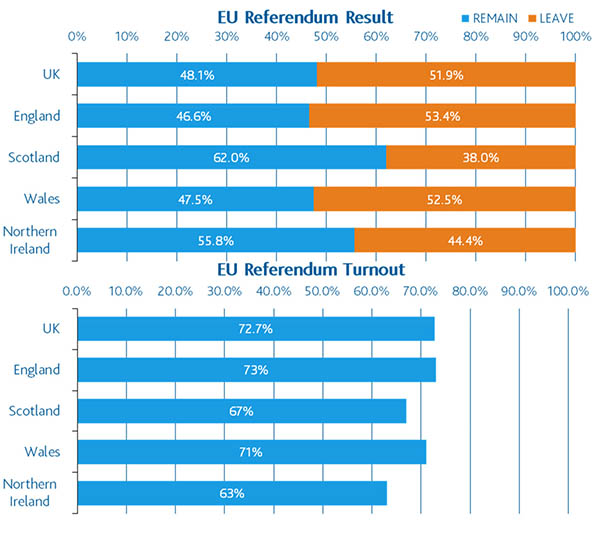

The stark contrasts in voting patterns across the countries and regions of the UK suggest that there may be longer-term institutional and constitutional implications for the country, which could also have macroeconomic impacts.

Nicola Sturgeon, Scotland’s First Minister, has already made clear that with Scotland voting overwhelmingly to remain, the result is indeed the "material change" she had previously insisted could lead to a second independence referendum.

Without offering a clear timeline, the First Minister said that a second ballot “is definitely on the table.” She plans to lay primary legislation in the Scottish Parliament required to host another referendum when it decides to do so.

Source: BBC

The next three months: business as usual (sort of)

David Cameron heads to the European Council meeting in Brussels on Tuesday, where the implications of the result, not only for the UK but also the wider European Union, will be top of the agenda.

Bank of England Governor Mark Carney has also spoken, emphasizing the Bank’s liquidity facility and its intention to do whatever is needed to maintain financial stability. The Bank’s Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) is next scheduled to meet on July 14. Mark Carney made it clear that they could act earlier if the market and macro backdrop merited it, though the potentially greater complexity of the post-Leave policy challenge they face means they are likely to prefer to lean on liquidity measures if they can continue to do so.

The UK will remain a member of the EU and retain access to the Single Market for some time to come, with existing rules and regulations staying in place. David Cameron stated that the process of triggering the UK’s exit via Article 50 of the Lisbon Treaty will be a decision for his successor. The subsequent exit could take up to two years to deliver.

Macro impact over the next 12-18 months: uncertainty is the key issue

Following the Leave result, we would no longer anticipate a post-vote bounce back in activity (primarily investment) delayed in the run-up to the referendum. UK gross domestic product (GDP) could be lower and unemployment higher than would have otherwise been the case, reflecting the medium-term impacts on markets, confidence, spending and investment.

We would normally expect inflation to slow in a weaker-growth environment, but the currency impact of the vote to Leave is likely to provide a boost to inflation.

As Governor Carney pointed out in the run-up to the referendum, this presents the Bank of England with a difficult trade-off: lower growth (which would normally point to additional policy stimulus) and higher inflation (which would conventionally trigger tighter policy). Hence the emphasis on liquidity measures in the short-term and Mr. Carney’s pre-vote statement that a vote to Leave could result in higher, lower or unchanged interest rates. That said, at the very least we would anticipate that interest-rate rises could be pushed well back from our pre-vote timetable (2017 Q2) 2and further rate cuts and/or quantitative easing remain on the table.

The macro impacts could both last into the long term and extend beyond the UK’s shores.

As immediate market moves have indicated, the potential macro impacts of the vote extend well beyond the UK. Other European countries are the most obvious candidates to take a hit, both as a result of their trade linkages with the UK and reflecting the fact that they are the other participants in the European project. The European Central Bank is therefore likely to respond. Indeed it has already done so with reassuring words. However, further policy action may be taken, if required.

There is also a direct read-through from the Leave campaign’s success to political risks from Eurosceptic parties in other European countries – including the key member states of Germany and France.

Market impacts

This result of the referendum had not been anticipated by markets or the pollsters. At the time of writing, European and Asian equity markets are down between three and 10% – but have bounced off their earlier lows. Developed bond markets, including the UK gilt3 market, are stronger, while European peripheral bond markets are weaker. Sterling is weaker against all major currencies but has also bounced off earlier lows.

All these asset price changes should be seen in the context of the significant moves in the run-up to the referendum – strength in equities and sterling and weakness in developed government bonds.

The statement from Governor Carney has given some comfort to investors. He has reminded market participants of the robustness of the financial system and the ability of the Bank of England to provide liquidity to markets. At the time of writing, markets – while having moved significantly – appear orderly and with adequate liquidity.

The macro-economic and political impacts of the referendum result, noted above, are likely to have significant ramifications for markets both in the UK and beyond over the coming months and years. As you would expect, we will monitor them and their implications carefully.

However, market reactions to this, or indeed any event, can be complex, interlinked and not necessarily immediate. There are also many other factors that do and may impact markets. Any market views on the referendum result will also need to be seen in this context.

1 Brexit is an abbreviation of "British exit", which refers to the June 23, 2016 referendum by British voters to exit the European Union.

2 Forecasts are offered as opinion and are not reflective of potential performance, are not guaranteed and actual events or results may differ materially.

3 Gilts are bonds that are issued by the British government, and they are generally considered low-risk investments.

Important Information

Lucy O’Carroll is chief economist, investment solutions, at Aberdeen Asset Management.