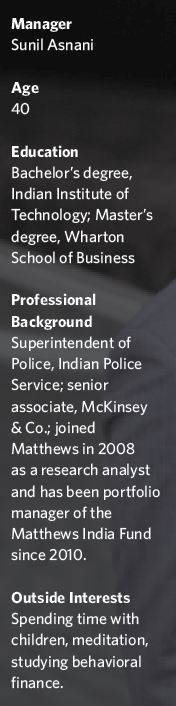

The 40-year-old Asnani’s observations come from years of experience both as a native-born Indian and an investor. His path to managing the fund started when he joined the Indian Police Service in Trivandrum, India, in the late 1990s after graduating from college with a degree in engineering. “There were a lot of very smart people out there with engineering degrees, and I wanted to use my people skills,” he says of the unusual career move.

After five years, which included a stint as superintendent of police, he headed to the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School of Business to obtain a master’s degree. After graduating in 2006, he worked for two years as a corporate finance consultant with McKinsey & Co. in New York before moving to San Francisco-based Asia investment specialist Matthews as a research analyst in 2008. He became lead manager of the India fund in 2010.

Fluent in several Indian dialects, Asnani says his background gives him a different perspective from most investors. “I have to say I am more skeptical of Indian companies than non-Indian investors, and I don’t take management statements at face value,” he says. To gather on-the-ground observations and speak to managers, he travels to India at least three to four times a year.

Given India’s corporate and government cultures, his skepticism is well-founded. Families virtually run many listed companies through seats on the board, which creates potential conflicts of interest and disputes among chief executives, shareholders and board members. Although India is a democracy, data from the last three federal elections in the past decade shows that more than one-quarter of elected representatives face criminal charges, in part because criminal underpinnings intimidate opposition voters, especially in poorer regions.

Inconsistent and excessive regulations add to the problems. Historically, the country has been held back by a tangle of overcomplicated, poorly implemented laws dating back to its independence and extending into the 1990s. Although there have been some policy improvements, rules governing land and labor markets remain restricted by red tape. Investors have been optimistic about Modi’s pro-business attitude, but Asnani believes the Modi government has yet to go as far in shaking up India’s bureaucracy as much as people were expecting. “I feel on a scale of 1 to 10, Modi has delivered about a 4 or 5,” he says.

India’s much-touted demographic profile, which is younger than that of other emerging market countries, may not necessarily be a plus, either. “On the one hand, a younger population opens up the potential for a bigger labor pool, greater productivity and a larger tax base,” says Asnani. “But without proper training and infrastructure, those things might not materialize to the degree many people hope for.”

“No doubt India has great potential and the wherewithal for rapid economic growth for decades to come,” noted Matthews research analyst Sudarshan Murthy in a report earlier this year. “However, long-term investors need to monitor changes in the underlying institutions.”

India: Last BRIC Bright Spot

December 1, 2015

« Previous Article

| Next Article »

Login in order to post a comment