Most discussions about retirement with consumers examine accumulation separately from decumulation. The research mostly addresses the years before retirement and how to achieve a wealth accumulation target.

Wade Pfau, an associate professor at the National Graduate Institute for Policy Studies in Tokyo, has noticed that the preponderance of research seeks a safe withdrawal rate. The typical retirement planning then uses this rate to compute a target for how much wealth needs to be accumulated so that the desired retirement spending can be funded from this wealth.

Pfau, however, who earned his Ph.D. in economics at Princeton in 2003, wonders in a research paper what would happen if he linked the accumulation and distribution phases together in an integrated whole.

"My findings suggest that a fundamental rethink about retirement planning is needed," he says. "When linking the accumulation and decumulation phases together, the concepts of 'safe withdrawal rates' and 'wealth accumulation targets' end up serving as almost an afterthought. Focusing on them is the wrong way to think about retirement planning."

Pfau's paper, "Safe Savings Rates: A New Approach to Retirement Planning Over the Lifecycle," which appeared in the May 2011 issue of the Journal of Financial Planning, hopes to frame the question of how much one needs to save, recognizing both one's saving for retirement and one's spending through retirement. If there is a "safe withdrawal rate" there should be a "safe savings rate." At what rate of savings does it always work out?

To get to this rate, he set up the problem like this: "The baseline individual wishes to withdraw an inflation-adjusted 50% of her final salary from her investment portfolio at the beginning of each year for a 30-year retirement period. Prior to retiring, she earns a constant real salary over 30 working years, and her objective is to determine the minimum necessary savings rate to be able to finance her desired retirement expenditures. Her asset allocation during the entire 60-year period is 60/40 for stocks and bills. Data is from Robert Shiller's Web page for the S&P 500 and Treasury bills."

Put another way, consider a person making $100,000 today who expects that salary to increase with inflation and who wants to withdraw $50,000 in today's dollars from her portfolio to supplement any other income, adjusting for inflation over a 30-year retirement. Based on market behavior since 1871, a 60/40 mix and ignoring taxes, there was never a time where saving at least X% of her salary for 30 years prior to that retirement didn't achieve those goals. Pfau solved for X.

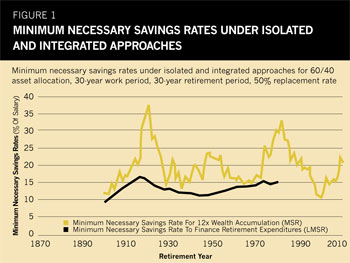

With the data going back to 1871, Pfau examined 30 years of savings followed by 30 years of withdrawals. Retirements would therefore have beginning dates ranging from 1901 to 1980. He found extreme volatility in the maximum withdrawal rates that turned out to be sustainable, ranging from just over 4% up to 10% in some periods. As one might expect, the higher withdrawal rates correlated to better markets and the lower rates to weaker markets during retirement.

Of course, a retiree does not know what the markets will do ahead of time. So assuming that the goal was to accumulate enough to use a 4% withdrawal rate, Pfau calculated what savings rate was needed to accumulate that amount. This is very similar to how most people approach retirement planning-isolating an accumulation goal to support an isolated set of parameters during distribution.

The savings rates required to accumulate enough to employ the 4% rule were every bit as volatile as the differing withdrawal rates. They ranged from 10.89% to 37.7%. If markets did well during retirement, less was needed to start the final 30 years, and if markets were poor, more was needed. When Pfau noticed that the periods of high required savings corresponded to periods where far less was actually needed during the subsequent retirement, he abandoned the 4% number and used actual retirement results to determine the needed savings. The volatility of the needed savings amount dropped significantly.

Figure 1 illustrates the difference between saving to make a targeted amount with a 4% withdrawal rate (blue line) and the savings needed based on actual results. Pfau frames the blue line as an accumulation of 12.5X salary, which is the needed amount to have 50% of salary equal 4%. He calls the black line the lifecycle-based minimum savings rate needed to finance the desired expenditures (LMSR) and considers the black line the main contribution of his paper.

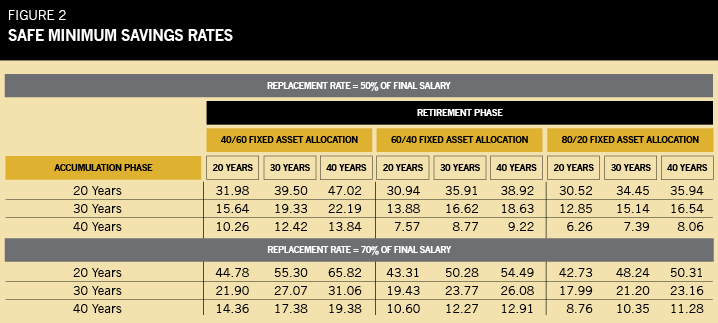

So what is "X" under the baseline case described earlier? Saving 16.62% of salary would have worked every time. Pfau's article also provides Figure 2, which shows results when certain variables change. It lays out 20-, 30- and 40-year savings spans, 20-, 30- and 40-year retirement periods, 40/60, 60/40 and 80/20 allocations, and replacement rates of 50% and 70%. For the typical 30-year retirement time frame, saving for 40 years cuts the safe savings rate to 8.77% while saving for only 20 years increases the safe rate to over 30%.

One reason for the much higher consistency of the needed savings is that good market environments tend to follow bad ones and vice versa.

Michael Kitces, author of The Kitces Report newsletter and the blog "Nerd's Eye View" at Kitces.com, has written and spoken about the effect of valuations on sustainable withdrawal rates. Low valuations portend better returns and therefore higher sustainable withdrawals. High valuations suggest lower withdrawal rates. Low valuations typically arise after weak market results.

Kitces' November 19, 2010 blog post pointed out just how much people with a specific accumulation goal at retirement depend on the last few years of savings to meet that goal. Using a straightforward calculation, Kitces found that a 25-year-old wishing to have $1 million at age 65 earning 8% needs to save $300 per month. Kitces points out, however, that at age 55, this saver still has less than $450,000. He quips that we would never say to a client that the plan was to "save for decades, build a base and then, in the last few years, quickly double up your wealth with investment growth and retire happily."

Two implications for planners of this reliance on compounding in the last few years leading up to retiring is that perhaps we should be advising clients to save more and/or preparing them for greater uncertainty about their retirement date if they insist on such a straight-line methodology. Pfau's paper suggests that by focusing on the percentage of income that needs to be saved and changing the time frame to one's lifetime instead of two distinct phases, tough years just prior to retirement may not be as problematic as one might fear from the near-retirement compounding problem.

Then again. At what initial withdrawal rate would a planner no longer be confident their client can retire? The numbers are what they are. We know everyone that saved at least 16.67% of their salary adjusted for inflation every year for 30 years was able to spend 50% of their final salary for at least 30 years, but none of these retirees or their advisors would have known what was to come at the time.

Dr. Pfau's blog, wpfau.blogspot.com, highlights a few specific retirees. The 1918 retiree, for instance, had to save the most (16.67%) to cover 30 years of retirement spending. The 1921 retiree had an initial withdrawal rate of 9.06%. How many of us would have sent this client confidently off into retirement at that point? There was no way to know then that the client could have made the next 30 years of spending with an initial withdrawal rate as high as 9.76%.

I doubt the "16.62% rule" will become as common as the "4% rule" often cited in discussions about safe withdrawal rates. It is true that on one level, Pfau's work merely reinforces the old advice that the best time to start saving is today. However, I look forward to the additional research I hope this lifespan approach may generate. Like the late Lynn Hopewell's "Decision Making Under Conditions of Uncertainty: A Wake Up Call for the Financial Planning Profession" and Bill Bengen's series on safe withdrawal rates, I hope this is the next Journal of Financial Planning contribution that leads to additional research and expands our body of knowledge.

Dan Moisand, CFP, has been featured as one of the America's top independent financial advisors by most leading financial advisor publications. He has spoken to advisor groups on five continents on topics such as managing investments and navigating tax complexities for retirees, retirement readiness, and most topics relating to the development of the financial planning profession. He practices in Melbourne, Fla. You can reach him at 321-253-5400 or dan@moisandfitzgerald.