Quick! Name the head groundskeeper at your favorite team’s stadium. Can’t recall? Not surprising, since those playing the game will be your focus rather than those who mow the grass. The groundskeeper is rarely if ever mentioned during the game nor interviewed by the media afterwards. The attention is on players and coaches and the critical decisions and plays they made during the game.

For the Federal Reserve, the groundskeeper for the U.S. economy, it is a different story. Since the economy plays an outsized role in our lives, we would feel better if someone were in charge. But the truth is no one is in charge. The economy’s impact on us is the result of the unfathomably complex interaction of billions of independent consumer and business decisions.

We find this unsettling, so we look to the Fed much as the residents of Oz did with their wizard, imbuing it with powers they do not have.

An aura of extraordinary importance surrounds the Fed as a result, with the press doing everything it can to perpetuate this myth. Thus, a huge number of economic and market stories mention the actions of the Fed, from the Fed raising interest rates to providing excess liquidity. These mentions happen so frequently that they turn into an availability cascade. We thus falsely conclude what the Fed is doing must be important, especially when making investment decisions.

Maintaining The Economic Playing Field

The Fed has two primary responsibilities. The first is to grow the money supply at a rate consistent with low inflation and strong economic growth. The second is to act as the lender of last resort, ensuring the integrity of the banking system. The latter can be thought as maintaining the “financial railroad” upon which the economy runs. If it breaks down, the economy collapses.

The late Milton Friedman famously suggested the first function could be best accomplished by replacing the Fed board with a computer that grew the money supply at a consistent 5 percent to 6 percent annually. In other words, put monetary policy on cruise control in order to avoid making big mistakes.

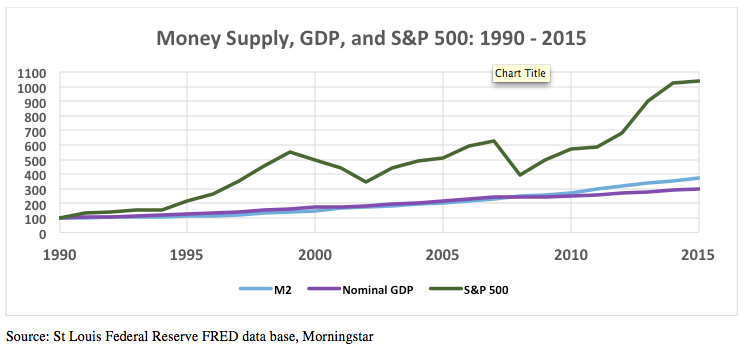

The chart below reports what has occurred over the last 25 years (1990 = 100). The money supply (M2) grew 5.5 percent annually and the economy (nominal GDP) by 4.5 percent, while the stock market’s annual return averaged 10.2 percent over this period.

Money supply and GDP grew consistently together during this period. Seminal 1960’s research by Milton Friedman and Anna Swartz concluded that money supply leads GDP, so it’s important to consistently grow money supply by 5 percent to 6 percent annually. The Fed has been largely successful in doing this since 1990, thus meeting its primary responsibility.

The stock market generated returns erratically over this period, as it always does. Fed actions have often been put forward as an explanation for this short-term volatility. However, evidence points to investor emotional overreactions as a more likely explanation.

However, the events of 2008 provided a glaring exception. The Fed chairman at the time, Ben Bernanke, made the horrible mistake of allowing Lehman Brothers to fail. Immediately, the federal funds market ceased to function, shutting down the economy’s financial railroad. The Fed failed as the lender of last resort.

To save the economy, the Fed injected massive liquidity into the banking system. I refer to the resulting excess reserves as the “Bernanke Mistake,” which haunts us to this day. If only he had initially acted as the lender of last resort, the great recession would have not been so great.

Busting Fed Myths

So now that we’ve busted a few of the myths surrounding the Fed and its impact, here are a few more:

Myth 1: Contrary to conventional wisdom, the Fed does not control interest rates. The Fed can set rates for a small fraction of financial transactions, but markets determine rates on the vast majority. The Fed attempts to influence where rates go, much like the Wizard of OZ with his elaborate set piece, but markets have the final say.

Myth 2: As a corollary to Myth 1, it is believed that the “Fed raising rates” hurts stock returns. Beyond rejecting the Fed setting interest rates, evidence reveals that most often rising rates beget higher stock returns. This is because rising rates are the consequence of stronger economic growth and this growth more than offsets the negative impact of rising rates on stock returns. Growth trumps rising rates when it comes to stock returns.

Myth 3: It is widely believed recent economic growth and stock returns are a consequence of Fed-supplied liquidity and not underlying economic strength. The initial Bernanke liquidity surge was critical to saving the economy. But over the last three years the Fed has systematically reduced excess reserves, yet the economy and stock market continue to grow. We are no longer in a liquidity-driven market. The Bernanke boil has been lanced and we are doing fine as it drains.

Ignore The Fed

The Fed plays a critical role in maintaining the playing field upon which all of us pursue economic activities. It is important to note that economic growth and the resulting market returns are the result of our collective efforts, with the Fed playing a supporting role. But since it is hard to identify a single economic “quarterback”, we gravitate to the Fed and project power and influence on them well beyond what is the case.

No disrespect to the Fed and Janet Yellen, as it is essential they grow the money supply at a rate consistent with low inflation and strong growth while acting as the lender of last resort. My targets, rather are those who over hype the Fed’s influence.

The best approach is to largely ignore the Fed and any analysis based on what they might do. I follow this approach as an equity portfolio manager. I check M2 growth rates from time to time but otherwise ignore the media-generated Fed circus.

And you should, too.

C. Thomas Howard, Ph.D., is CEO and director of research at AthenaInvest Inc., a behavioral portfolio management company.