Market meltdowns are the investing world’s equivalent of a merciless tsunami, and when they occur the devastation to portfolios can be ugly. Investors have witnessed two such major market meltdowns since the turn of this century. One occurred between 2000 and 2002, when the S&P 500 index plummeted 49%. The other ran from 2007 to 2009, when the stock market fell 57%.

While many people believe diversification and asset allocation are an effective way to staunch the bloodletting during such events, that hasn’t proved to be the case, says Randy Swan, president and CEO of Swan Global Investments and manager of the Swan Defined Risk Fund. “Since the beginning of time, the industry has been promoting diversification as the solution to risk,” he says. “But history shows it doesn’t work too well in severe market corrections.”

The main reason is the tendency for even seemingly different asset classes to choke together during times of extreme market stress. The performance of target date funds during the most recent bear market illustrates that point. Even though they invested in a mix of stocks and bonds, and were among the most conservatively invested funds at the time, the average fund in the Morningstar Target Date 2000-2010 category lost an average of 31% during the 2007-2008 market correction. It took three full years to recover those losses.

By contrast, the Swan Defined Risk Strategy has kept the bear at bay since Randy Swan first began using it at his Durango, Colo., firm for separately managed accounts 19 years ago. While it leaves room for some upside participation, it shows its strength particularly well in severe bear markets. In 2008, for example, the strategy fell just 4.5% as the market tumbled 37%. Over the long term, it has also captured about 61% of the market’s upside.

Swan’s strategy is based on options strategies designed to control risk while also giving investors a shot at reward. The rules-based process starts with the S&P 500, which Swan taps through nine equally weighted ETFs that represent each sector of the index, and he remains invested in these at all times. In an attempt to limit portfolio losses, the fund then purchases long-dated put options (which are at or near the money) on the ETFs. (These give a buyer the right to sell assets by a particular date at a stated price.)

The long-dated options are purchased every year, usually toward the end. In addition, the fund also tries to generate income and reduce risk by selling short-term puts and calls.

Unlike many of his peers who use options in their strategies, Swan doesn’t try to time the market or bet on specific company stocks. “Our system is not based on market timing predictions or judgments about particular companies,” he says. “We take a rules-based approach, and that separates us from tactical or long/short managers.”

The technique sets parameters for how much the fund can lose, or gain, in a given year. If Swan sets a downside limit of 8%, for example, he invests the fund to lose no more than about that amount even in a worst-case scenario.

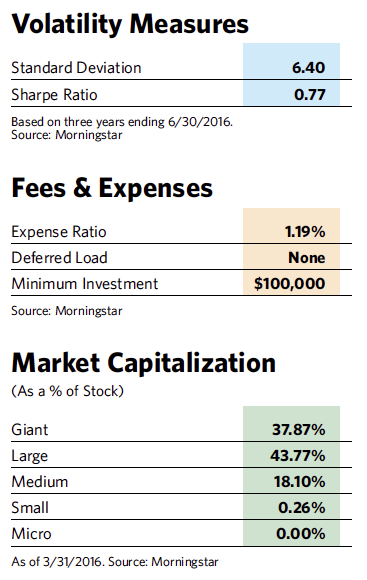

But the approach also limits upside potential in bull markets. From the fund’s inception in 2012, its institutional class shares have had an average annualized return of 4.36% through March 2016, while the S&P 500 returned 12.9% during the same period. Volatility poses a challenge, however. In turbulent 2015, for instance, the fund’s institutional shares fell 4.3% while the S&P 500 rose 1.4%.

Swan sees the fund as a kind of insurance against disaster. “Our approach is about providing true bear market protection, as opposed to the 5% or 10% corrections we’ve seen in recent years,” he says.

Over the longer term, he says, his ability to limit losses when the market tanks has been a powerful and positive driver of returns. Swan Global Investments has been using the same strategy employed by the fund since 1997 for separately managed accounts. According to the firm, a $100,000 investment in the Swan Defined Risk Strategy between 1997 and March 2016 would have grown to $459,215 (net of fees), while the same investment in the S&P 500 would have grown to $329,743 and would have grown to $324,306 in a 60/40 portfolio of stocks and bonds. On an annualized basis, that translates into an 8.47% return for the Swan strategy, a 6.57% return for the index and a 6.48% return for the balanced portfolio.

The strategy has also produced much less volatility than the index over the long term. Its standard deviation has averaged 9.79%, while the index has averaged 15.49% and the balanced portfolio 9.31%. The strategy’s 0.64 Sharpe ratio (a measure of risk-adjusted returns) exceeds the ratios of the index and the balanced portfolios by a considerable margin.

The approach appeals to clients of all ages, Swan says. “For people in retirement, a 50% loss in a portfolio can be devastating. And for people in the accumulation phase, having a large variance in return brings portfolio returns down over time.” He adds that while the strategy was designed as a substitute for a balanced stock and bond portfolio, even a 20% allocation to the fund can have a meaningful impact on overall volatility and returns.

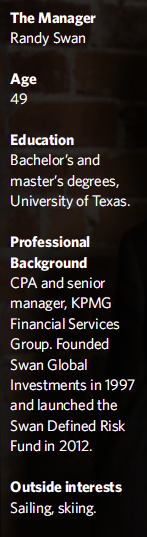

Before founding what would later become Swan Global Investments in 1996, Swan was a CPA and senior manager for KPMG’s Financial Services Group, primarily working with insurance companies and risk managers. That experience taught him firsthand how insurance companies manage risk, and how it might apply to the investment world through options trading.

“I’ve been an avid investor since I was 14,” he says. “But it wasn’t until I worked at KPMG that I recognized the benefit of managing the risk side with options. It’s like a lightbulb went on.”

Swan developed the methodology as a way to protect clients from large losses while still letting them enjoy a decent dose of the market’s upside. He started out using a market-cap-weighted exchange-traded fund that follows the S&P 500, but switched to equal weighting in 2012 to avoid becoming too heavily invested in overheated sectors.

Growth progressed slowly during the firm’s early years. It wasn’t until the market crash of 2008—over a decade after he set up shop—that investors began to recognize the value of not losing money as well as the pitfalls of traditional diversification. By 2013, his assets under management had reached $1 billion.

Today, Swan Global Investments has nearly $3 billion in assets under management and 40 employees. One of them is Randy’s brother Rob, a former flight-test engineer and software developer who handles the technology and trading end of the business. The pair manage the strategy for numerous asset types, such as large-cap stocks, emerging market stocks, foreign developed stocks, small-cap stocks, long-term bonds and gold. Besides the Swan Defined Risk Fund, the firm has other mutual funds covering small caps, foreign developed stocks and emerging markets, and these also employ his process.

Two years ago, Randy Swan established an office in Puerto Rico, where he now works with five other employees and enjoys sailing and fishing in his spare time. Rob continues to supervise the Durango office. The company also has an office in Tampa, Fla., with about 10 employees.

Swan sees the untraditional office setup and his staff’s backgrounds as a reflection of the firm’s unusual way of doing things. “We like to call Durango the business capital of southwest Colorado,” he says. “Most of us come from a math or science background, rather than finance. I think it all plays into why we think outside the box.”

Another point of departure for Swan is his open attitude toward bear markets, when his funds tend to shine. “We don’t need the Dow to hit new highs to reach our goals and objectives,” he says. “In fact, we’d prefer a market selloff within the next two or three years.”

Although he won’t predict whether that will happen, he sees it as a distinct possibility for several reasons. There hasn’t been a major downturn in over seven years, so a true bear market is overdue. Even though the Federal Reserve and banks around the world have kept interest rates at historic lows for years, economic growth remains anemic. And the federal budget deficit continues to loom.

If things do head south, he believes, as he has for nearly 20 years, that traditional diversification won’t provide much of a safety net. “Stock dividends, which historically have made up a large part of total return, are extremely low. And fixed-income, the part of the portfolio that’s supposed to provide some protection against equity risk, won’t be able to hold up its end of the bargain if interest rates rise. That’s not a good combination.”