If you ask most mutual fund managers where they think the economy is headed, many would respond that their job is to select securities and construct portfolios, not to try and forecast the direction of the economy.

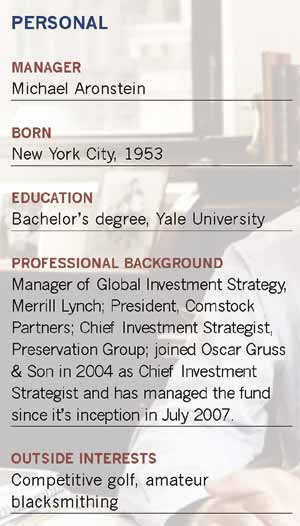

Michael Aronstein, portfolio manager of the Marketfield Fund and the chief investment strategist for Oscar Gruss & Son, is a notable exception. In the past he has called pivotal economic turning points, including the 1987 stock market crash, the recent bursting of the housing bubble and last year's downturn in commodity prices.

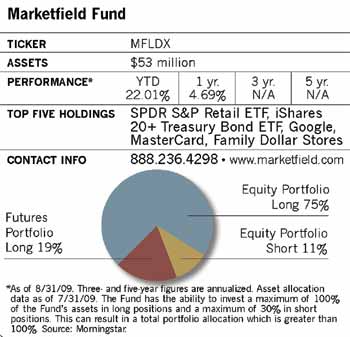

Such calls help explain why his $44 million absolute return fund, which employs strategies such as selling short and investing in commodity futures contracts, managed to lose only 13% in 2008 while the S&P 500 index lost 37%. This year, Aronstein lightened up on those short positions and moved into stocks he thinks will benefit from an economic rebound. But still the fund is beating the index by a considerable margin.

The 55-year-old fund manager is now taking a stance many people view as contrarian. As the majority of economists look for a weak and gradual recovery, Aronstein believes we will see a sharper, more pronounced rebound that takes many by surprise.

"The collapse in economic activity late last year was driven by the shutdown in the global capital markets," he says. "The subsequent restoration of liquidity in those markets and in the banking system should allow economic activity to begin returning to more normal levels over the next several months. The recent decline was an event shock rather than a gradual process, and recoveries from such shocks tend to be quite powerful."

To Aronstein, the key to successful investing is figuring out pivotal economic inflection points, and when he recognizes them, shifting his investment strategy accordingly. Economists, he says, often do a poor job of predicting such turning points. "Traditional economic analysis looks at what has happened in the past. The problem is that each economic cycle, and the reasons behind each drop and recovery, is different."

He also takes issue with traditional allocation models. As more investors own the same securities through broad indices, assets and strategies have become much more correlated, especially when things go wrong. "The efficient frontier proved to be a long, deep precipice," he says.

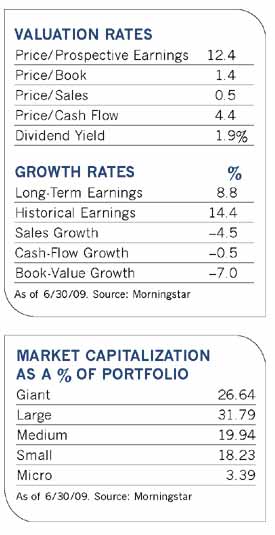

In the management of his own portfolio, Aronstein's selection of individual stocks takes a back seat to broad economic themes. He says it's hard for investors to gain a durable advantage by picking stocks when Wall Street research and other information on midsize and large companies are so widely disseminated.

He does no proprietary research to fill the sector sleeves of the portfolio, preferring instead to talk to a network of analysts, money managers and even business owners to see what stocks they recommend. Besides buying individual securities, he also makes liberal use of exchange-traded funds for broad sector participation. The fund's 76 holdings are widely distributed, and the top ten holdings represent just 17.5% of assets.

Aronstein considers himself a long-term investor, but market volatility has shortened his holding periods. "Normally, we make major decisions based on macroeconomic factors every couple of years. This time around, there have been three such decisions in the last 18 months."

He likens his Marketfield portfolio to a hedge fund for smaller investors, minus the illiquidity, high fees and opaque operations. The fund has a $25,000 investment minimum, though advisors can allocate smaller amounts for individual accounts. Expenses are capped at 1.75%.

His first priority is to help investors preserve capital, using a wide range of investments, rather than beat a particular index or benchmark in a particular style category. Besides shorting equities and investing in commodities futures, the fund's broad charter also allows him to use fixed-income securities and options. "Some people categorize the fund as absolute return, others call it long-short," he says. "My view is that the fund is designed to shepherd assets in any kind of market environment."

Recovery Plays

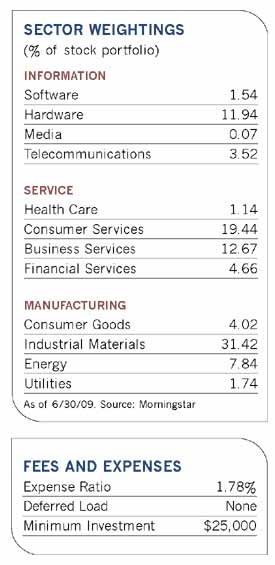

With the economy in recovery mode, Aronstein is steering the fund toward cyclical stocks in the consumer discretionary and industrial materials sectors, which tend to rebound sharply in economic upturns. He holds an exchange-traded fund in the retail sector, for example, as well as individual stocks for MasterCard, Sears, Family Dollar Stores and Ford. The fund also has sizable positions in manufacturing and transportation as well as in information technology, which has less inherent risk, Aronstein believes, and is benefiting from the increased global dependence on IT products.

On the other hand, he is wary of health care stocks. Although some investors see these equities as a safe haven, the recent proposals for health care reform have made investing in them "a matter of political guesswork," says Aronstein, and evaluating the industry according to more general macroeconomic forces has become all but impossible. Instead of the health care reform ideas being pushed around in Washington, Aronstein thinks a better solution would be to introduce more competition among insurance providers and for employers to treat health insurance as a taxable benefit.

Because of his positive economic outlook, the fund is now using short positions in less than 10% of its assets, down from last year when, during his more bearish posture, he held short positions in anywhere from 20% of the portfolio to its 30% short maximum. Most of those shorts were in the battered real estate and financial services sectors. Now, most of his short positions are in financials and, to a lesser extent, emerging markets.

His positions have declined on the long side as well since the beginning of the year, but for different reasons. The fund now has about 65% of assets in long positions, down from 70% to 74% from February until April. "This past spring looked like a once-in-a-lifetime give-up," he says. "That's as about as aggressive on the long side as I would ever be."

The rest of the fund is in commodity futures contracts tied to industrial metals as well as in gold, cotton, rice, wheat and other commodities.

Looking For The Inflection Point

Aronstein's current bullishness on the economy and the stock market is tempered by his concerns about how the actions of the federal government and regulators will affect the economy over the long term.

"We are navigating between two macroeconomic currents," he wrote in a recent letter to shareholders. "On the one hand, we see restorative forces of capital markets and monetary liquidity setting the stage for a surprisingly vigorous recovery in overall economic activity." But these beneficial forces could be thwarted, he says, by reckless spending and several new regulations and tax initiatives that can do long-term harm to economic functions in the U.S.

He believes that the Federal Reserve's emergency measures to address the credit crisis were necessary and have worked fairly well.

Short-term rates are near historic lows, which is giving borrowers access to credit. High-grade corporate bonds have rallied, and the issuance among investment-grade companies has increased. Credit, while rationed by a crippled banking system, is available for high-quality borrowers.

But actions taken by Congress to stimulate the economy will "turn out to be a waste of time and money," he says. "Their lasting effect will be to distort the distribution of resources within our economy and ensure a long-term real growth rate below what it would have been without political intervention." He fears that current proposals related to tax policy, carbon emissions controls and international trade are harmful to long-run prospects for growth. And history shows that while regulatory reforms may provide a patch for certain problems, they consistently fail to protect the financial system as a whole from malfeasance and abuse.

Increasingly, he says, the U.S. economy will be shaped by government intrusions into the private sectors, which could eventually suppress any anticipated cyclical recovery. "Because competition and free-market pricing are the basis of our capitalistic system, any attempt to subject these to political control will distort the distribution of resources and undermine the efficiency and productivity of the economy as a whole," he maintains.

For now, however, the fund's stance remains fairly bullish. While government policy decisions could have a long-term impact, and inflation could kick up as the credit crunch eases, these are not yet driving themes shaping his portfolio. "Our sense is that current constructive market forces will prevail in the short-to-intermediate term," he says.

But, as always, Aronstein is keeping an eye out for the next economic inflection point that will signal a change in strategy. "The time to worry," he says, "is when the consensus view begins catching up with our own."