I suspect that much of the anger we see is felt by people who thought they would never suffer financially. They were doing well, but then something happened – a job loss, a medical crisis, drug addiction, bad investments, something pushed them down the ladder. Maybe it was their own mistakes, but they don’t like life on the lower rungs and don’t think they should be there.

Neal Gabler goes on to talk about the overriding shame that follows:

You wouldn’t know any of that to look at me. I like to think I appear reasonably prosperous. Nor would you know it to look at my résumé. I have had a passably good career as a writer – five books, hundreds of articles published, a number of awards and fellowships, and a small (very small) but respectable reputation.

You wouldn’t even know it to look at my tax return. I am nowhere near rich, but I have typically made a solid middle- or even, at times, upper-middle-class income, which is about all a writer can expect, even a writer who also teaches and lectures and writes television scripts, as I do. And you certainly wouldn’t know it to talk to me, because the last thing I would ever do – until now – is admit to financial insecurity or, as I think of it, “financial impotence,” because it has many of the characteristics of sexual impotence, not least of which is the desperate need to mask it and pretend everything is going swimmingly. In truth, it may be more embarrassing than sexual impotence.

“You are more likely to hear from your buddy that he is on Viagra than that he has credit-card problems,” says Brad Klontz, a financial psychologist who teaches at Creighton University in Omaha, Nebraska, and ministers to individuals with financial issues. “Much more likely.” America is a country, as Donald Trump has reminded us, of winners and losers, alphas and weaklings. To struggle financially is a source of shame, a daily humiliation – even a form of social suicide. Silence is the only protection.

I’m no psychologist, but I think psychologists would say that suppressing emotions like shame and anxiety, anger and frustration is terrible for your health. I would bet doing so is part of the reason for the rising middle-age death rate I wrote about last year (see “Crime in the Jobs Report”).

Yet I understand why people keep quiet about lifestyle setbacks. Our culture in the US preaches a survival-of-the-fittest “social Darwinism.” We assume people get what they deserve; and if they don’t succeed, it must be their own fault. So it’s no surprise people hide or downplay their misfortune. Gabler is a brave exception on that point.

In fact, material success (or lack thereof) tells us almost nothing about a person’s character, values, intelligence, or integrity. Sometimes good, hard-working people have bad luck. Lazy idiots can have good luck. I don’t know why.

In either case, bad luck is not what enrages so many people. The unprotected are angry because they believe the game is rigged against them. Moreover, they think the protected class rigged has the game.

Permanent Damage

As bad as the situation is, official data says it’s improving. Just look at the unemployment rate, down to 5% and job openings everywhere.

Those numbers look quite different from the perspective of the unprotected. The data doesn’t account for underemployment, lowered wages, and job insecurity. If you spend a few hours cutting your neighbor’s grass for 50 bucks and don’t make another penny, you still count as “employed” that month.

Gallup has an enlightening statistic. Their Gallup Good Jobs Index measures the percentage of the adult population that works 30+ hours a week for a regular paycheck. It stood at 45.1% when I checked this week.

Last week’s jobs report told us that 62.8% of the civilian noninstitutional population participates in the labor force, and 5% are unemployed, while Gallup tells us only 45.1% have what it considers a “good job.” These aren’t directly comparable datasets, but a rough estimate suggests that maybe a fifth of the labor force is either unemployed or have less-than-good jobs.

The picture gets even murkier. Last week my good friend (and onetime business partner) Gary Halbert reported a new survey from the Society for Human Resource Management. Their data says American workers actually feel pretty good. Some 88% of employees said they were either “very satisfied” or “somewhat satisfied” with their jobs.

Yet the same survey found that 45% were either “likely” or “very likely” to look for a new job in the next year. So it appears their satisfaction is limited. This survey doesn’t include unemployed workers who also aren’t satisfied with their status.

That 5% unemployment number masks a seriously low participation rate, falling productivity, and a serious surge in low-wage service jobs, coupled with a loss of middle-class jobs. It is skewed by the soaring number of temporary workers, involuntarily self-employed workers, and contractors and freelancers in the gig economy who are technically counted as employed. In other words, 5% unemployment today is not your father’s 5% unemployment. There is a reason it feels substantially different.

So millions, dissatisfied with the eroding American Dream, struggle to make ends meet, despite a historically low unemployment rate. Merely finding a job, while necessary and welcome, didn’t begin to solve their problems.

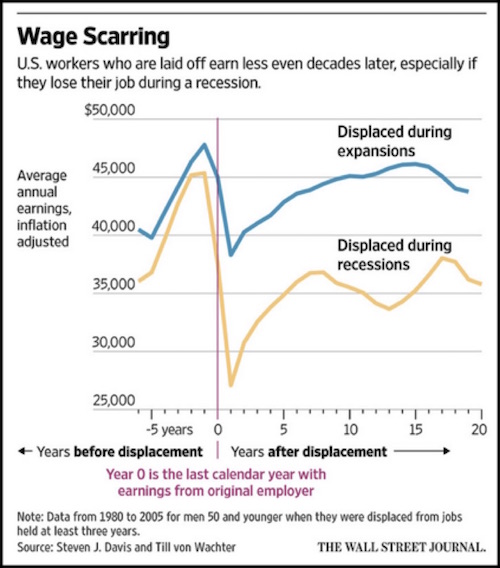

A May 9 Wall Street Journal story reported some research on this point. People who lose jobs in a recession experience a variety of long-lasting effects. Their new jobs often pay them lower wages, and it takes years for them to reach their previous earnings peak. These people are less likely to own a home; they experience more psychological problems; and their children perform worse in school. The WSJ calls this phenomenon wage scarring.

We know from BLS data that about 40 million Americans lost their jobs in the 2007–2009 recession. Many still feel the financial pain, despite having landed new jobs. Says the WSJ:

Only about one in four displaced workers gets back to pre-layoff earning levels after five years, according to University of California, Los Angeles economist Till von Wachter. A pay gap persists, even decades later, between workers who experienced a period of unemployment and similar workers who avoided a layoff. Estimates vary, but by one analysis, people who lost a job during recessions made 15% to 20% less than their nondisplaced peers after 10 to 20 years.

It gets worse. At some point these people will reach retirement age with little or no savings. They will either keep working – possibly in jobs that would otherwise go to younger workers – or they will live frugally and depress overall consumer spending. That’s not good for anyone.

Think about it. These were probably people who had developed an acceptable lifestyle and were likely saving money and being responsible. Then they lost their jobs, and even now that they’re working again, their pay is still 20% lower than it was. It’s tough to maintain that former lifestyle and still save. And when your house is underwater, selling it and moving down is both difficult and gut-wrenching.